History of Nea Kessani

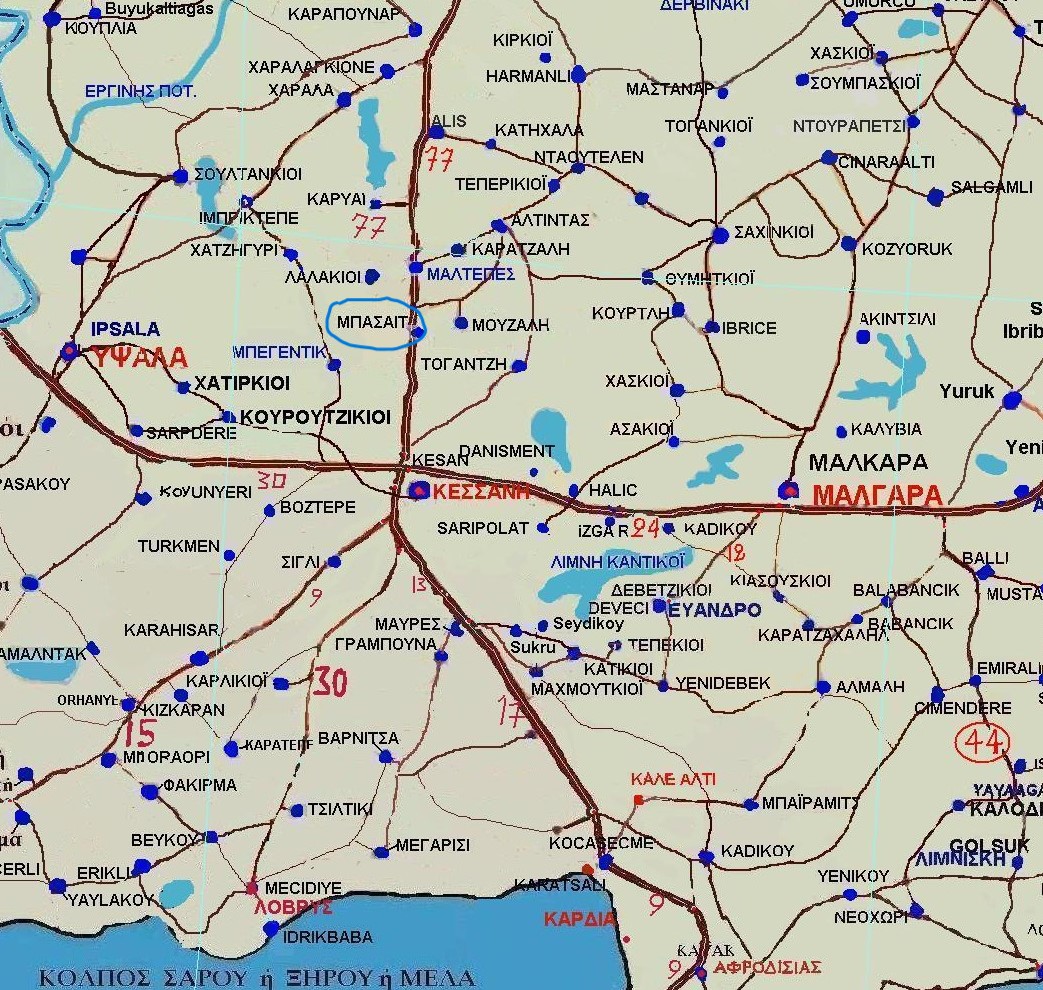

Nea Kessani is a refugee village. It was founded because, 90 years ago, the loss of Eastern Rumelia and Eastern Thrace was finalized, and the Greek inhabitants of those regions had to leave their ancestral homes, their properties, their households—to become refugees and build a new life in new, yet still Greek, homes in Macedonia, Thessaly, and of course Western Thrace. Thus were born Plastiria and Nea Kessani. Its charm lies, among other things, in the fact that it was founded by refugees from different places: the majority came from the villages Katikioi of Makra Gefyra and Basait of Kessani (Eastern Thrace), but also from the village Agios Vlassis of Mesimvria (Eastern Rumelia). Additionally, some families came from the town of Kessani, from the villages Tsildikioi, Karadza–Halil, and Begentikioi (Kessani area), Kistritsa (Charipopolis area), others from Bana of Mesimvria, some from Asia Minor, and three Sarakatsani families settled during World War II. Strong people, the unsung heroes of history, with some differences in customs and mentality but united by the same pain of uprooting, came to this small corner of the world and, setting aside their differences, created a thriving community, never forgetting their “homeland.”

Nea Kessani from above

19th century until 1922

In the second half of the 19th century, the miserable state of the Ottoman Empire and Russia’s ambitions led to a new Russo-Turkish war in 1877, which ended in a disastrous defeat for Turkey and the famous “Treaty of San Stefano,” which fulfilled even the wildest dreams of the Slavs, while Greece was gravely harmed and reacted, albeit in vain. From Thrace, the area south of the Rhodope Mountains and east of Porto Lagos remained with Turkey, while the rest was included in Bulgaria, as was nearly all of Macedonia. However, fearing Russia’s advance toward the Mediterranean, the European powers decided that Northern Thrace—between the Balkan and Rhodope mountains—should be removed from the map of Greater Bulgaria in the Treaty of San Stefano and become an autonomous province of the Ottoman Empire. The administration was undertaken by the three cohabiting nations (Greeks, Turks, Bulgarians).

This autonomy, however, for the Bulgarians marked the first step toward annexation of the area to Bulgaria, and they orchestrated the Bulgarization of the Greek Thracians. At that time, the Greeks in Northern Thrace had 5 Metropolises, 13 central churches, 100 chapels, 10 monasteries, and 66 schools with 8,000 students and 186 teachers, but they were a minority. Thus, “plans” began to be implemented, including the prohibition of the Greek language, economic exclusion of Greek professionals, arbitrariness, and much violence. Nevertheless, the effort was unsuccessful. The Thracians endured and did not lose their national consciousness. Eventually, it was decided to carry out a mutual population exchange, with Bulgaria paying Greece 200 million drachmas. By 1924, the last remaining Greeks departed, heeding the call of Venizelos, and left their beloved homeland. Among them were some of the future founders of Plastiria. Of interest is the testimony of Mr. Thanasis Ekmektsis, a refugee from Agios Vlassis, who said they came to Greece in 1924 more out of love for Greece, their homeland, than because they were expelled. Perhaps their village was spared the anti-Greek rage of the Bulgarian administration.

Meanwhile, the Young Turks, with their initially modernizing and democratic facade, inspired hopes in Greeks, Turks, and Europeans, but soon revealed their ill intentions. After World War I, new dark chapters of persecution, massacres, and destruction were written in Eastern Thrace with the blessing of the European powers and the orchestration of a special Turkish committee established in Raidestos for the theoretical approach of the cleansing plan. During 1915–16, nearly 69,000 Greeks were deported from all of Thrace and while the Patriarchate protested in vain to the Sublime Porte, which gave false promises, Hellenism was being exterminated in labor battalions, forced labor, and campaigns deep into Asia Minor. Even Turkish newspapers protested.

As for Western Thrace, political negotiations with the European powers led to the liberation first of Xanthi in October 1919 and then of the entire Western Thrace in May 1920. Greece was represented in the negotiations by Eleftherios Venizelos, who is credited with the diplomatic triumph of the Treaty of Sèvres, signed on August 10, 1920, between Turkey and the European powers. With this treaty, most of Eastern Thrace was ceded to Greece, while the area of Constantinople and the Straits came under Allied control, Greek sovereignty was recognized over the Dodecanese, Imbros, and Tenedos, and Turkey was confined to central and northern Anatolia.

A major figure of the time was Charisios Vamvakas, a representative of Greek interests in Thrace, who worked intensively for the regeneration of our then nearly destroyed region. Under Greek sovereignty, Thrace was reorganized and services of internal administration, education, public works, agriculture, justice, refugee relief, healthcare, and transportation were immediately established.

Unfortunately, the Treaty of Sèvres was, as described, “as fragile as Sèvres porcelain”—Thrace’s freedom did not last long. Soon came the greatest tragedy of modern Greek history, the Asia Minor Catastrophe. The chimera of the Great Idea prevented the Greeks from seizing historical opportunities, and they paid dearly for this mistake. After the failed campaign in Asia Minor, the Allies ensured favorable resolutions for themselves. Through the Treaty of Mudanya, they handed Eastern Thrace back to Turkey, nullifying the protection the Greek army had provided for three years on the Asia Minor side of the Straits. Eleftherios Venizelos stated in a telegram, “Eastern Thrace was unfortunately lost for Greece and returns to the direct sovereignty of Turkey… Moreover, we are obliged to evacuate Thrace from now. My entire effort is directed at saving as many Thracians as possible despite losing Thrace… As tragic as it may be, it is necessary for the Thracians to abandon the land that they and their ancestors have inhabited for centuries—there is no other means of salvation for them…” The departure of the Greek army began immediately, followed by 250,000 Eastern Thracian refugees. Only those who witnessed the sorrowful image of the Hellenism turned into refugees can understand and describe the magnitude of the catastrophe.

The ox-cart caravan through Adrianople (photo from the site MODERN GREEK HISTORY)

The American author Ernest Hemingway wrote on October 7, 1922, in his dispatch for the Toronto Daily Star: “ADRIANOPLE – In an endless and heart-wrenching march, the Christian population of Eastern Thrace crowds the roads leading toward Macedonia. The main mass, crossing the Evros River at Adrianople, stretches over forty kilometers. Forty kilometers of carts pulled by cows, young bulls, and muddy buffaloes, filled with exhausted, bewildered men, women, and children. Covered with blankets over their heads, they march blindly through the rain beside their worldly goods. This faceless river is draining the entire surrounding region. They do not know where they are going. They have abandoned their fields, their villages, their fertile, brown earth and joined the river of fugitives upon hearing of the Turks’ approach.”

The final end came on July 24, 1923, with the signing of the well-known “Treaty of Lausanne.” Greece was required to evacuate Smyrna and Eastern Thrace. At least its sovereignty was recognized over the islands of Lemnos, Samothrace, Lesbos, Chios, Samos, and Ikaria, while Turkey retained Imbros and Tenedos. The borders in Thrace separating Turkey from Greece and Bulgaria were also settled, and a Greek-Turkish agreement mandated the compulsory exchange of populations.

Thus, with the Treaty of Lausanne, the epilogue of the tragedy of the Thracian Greeks was written. We now know that responsibility lies with the Greek political and military leadership, but also with the policies of our “Allies,” who committed yet another injustice—inevitably—in the name of their interests. This injustice, like every other in world history, was paid for by civilians—the hundreds of thousands of Greek Thracians who overnight became refugees and were forced to leave their homeland. They gathered what they could from their homes, along with great courage, and set out for new settlements in Macedonia and Western Thrace, where they settled and managed to stand on their feet. They turned destruction and poverty into creativity and development, while simultaneously reinforcing Greece’s national population and creating thriving communities, which they named after the regions they came from: Nea Raidestos, Neos Skopos, Neoi Epivates, NEA KESSANI.

At this point, I think we should mention the main regions from which the founders and residents of our village came:

Basaït or Basiki

Basaït belonged to the administrative region of Kessani, which was a transportation hub connecting Adrianople and Makra Gefyra to Gallipoli, and from Raidestos and Malgara to Western Thrace, giving it significant commercial and strategic importance. Kessani (or Kissini) was also known as Rouskioi, and appears under that name on many maps. It was renamed Kessani by the Greek administration in 1921. Before 1920, it was the seat of a kaymakam and belonged administratively to the province of Gallipoli. Later, under Greek occupation, it became the seat of a sub-governor and had jurisdiction over 55 villages and settlements. The population of Kessani before 1912 was about 10,000 and engaged in agriculture, livestock farming, and trade. However, due to anti-Greek persecution, this number fell to 5,300 by 1920. Ecclesiastically, Kessani was under the Metropolitan of Heraclea. With the population exchange, Kessani was completely stripped of its Greek population and declined. The families of Savvas Galimaridis, Alkiviadis Diavis, Panagiotis Xanthopoulos, and Giannis Karamousalidis originated from Kessani itself. The village of Basaït was 5–6 kilometers from Kessani. It was inhabited by 500 families, all Greek. They lived off agriculture, cultivating wheat, hempseed (kanavouri), and sesame, and also raised livestock. About 30 families settled in Plastiria after staying briefly in Didymoteicho and Sappes.

Katikioi

The village of Katikioi belonged administratively to Makra Gefyra, a town in Eastern Thrace, which in turn belonged to the Sanjak of Adrianople. The province of Makra Gefyra included the following villages: Kavakli, Psathades, Katikioi, Kavatzik, Dervenaki, Malkots, Louloukioi, Tsiflikaki, Mastanar, Karamtsa, Eskikioi, Kirkioi, Derekioi, Kosti, Dogankioi, Kurt, Mega Zaloufi, Madzi-Kadikioi, Karahalil, Zaloufaki, Aslan, Karampanar, Yaoupkioi, Katychala, Pasia-Yenitze, and Neberikioi — all Greek. Spiritually, it belonged to the Metropolis of Heraclea, represented by an archpriest. The town was situated along the railway line that led either to Constantinople or to Adrianople and Alexandroupolis. Its name came from the nearby bridge that was 1,392 meters long and 5.5 meters wide with 174 arches. In Turkish, it was called Uzun-Kopru or Tizeri-Ergine (= left of the Ergine river, which the bridge crossed), and it was a noteworthy commercial center. Katikioi was entirely Greek, had a primary school, and its roughly 500 residents were primarily engaged in farming and livestock breeding. They were dynamic, free-spirited, and peaceful people.

Agios Vlassis

Agios Vlassis was a small village in Mesembria on the western coast of the Black Sea, with 80 families. It bordered the villages of Naimona (Aimos) and Bana (from which three of the families who settled in Plastiria originated), and was about 1.5 hours from Mesembria. Built on the southern slope of the mountain, at the far eastern end of the Minor Haemus range, the location was enchanting with its rich and varied vegetation, dense forests rich in timber, clear springs, beautiful sea, and remnants of ancient temples and Byzantine monasteries — grand and now silent testimonies of the area’s Greek heritage, a land once famed and prosperous.

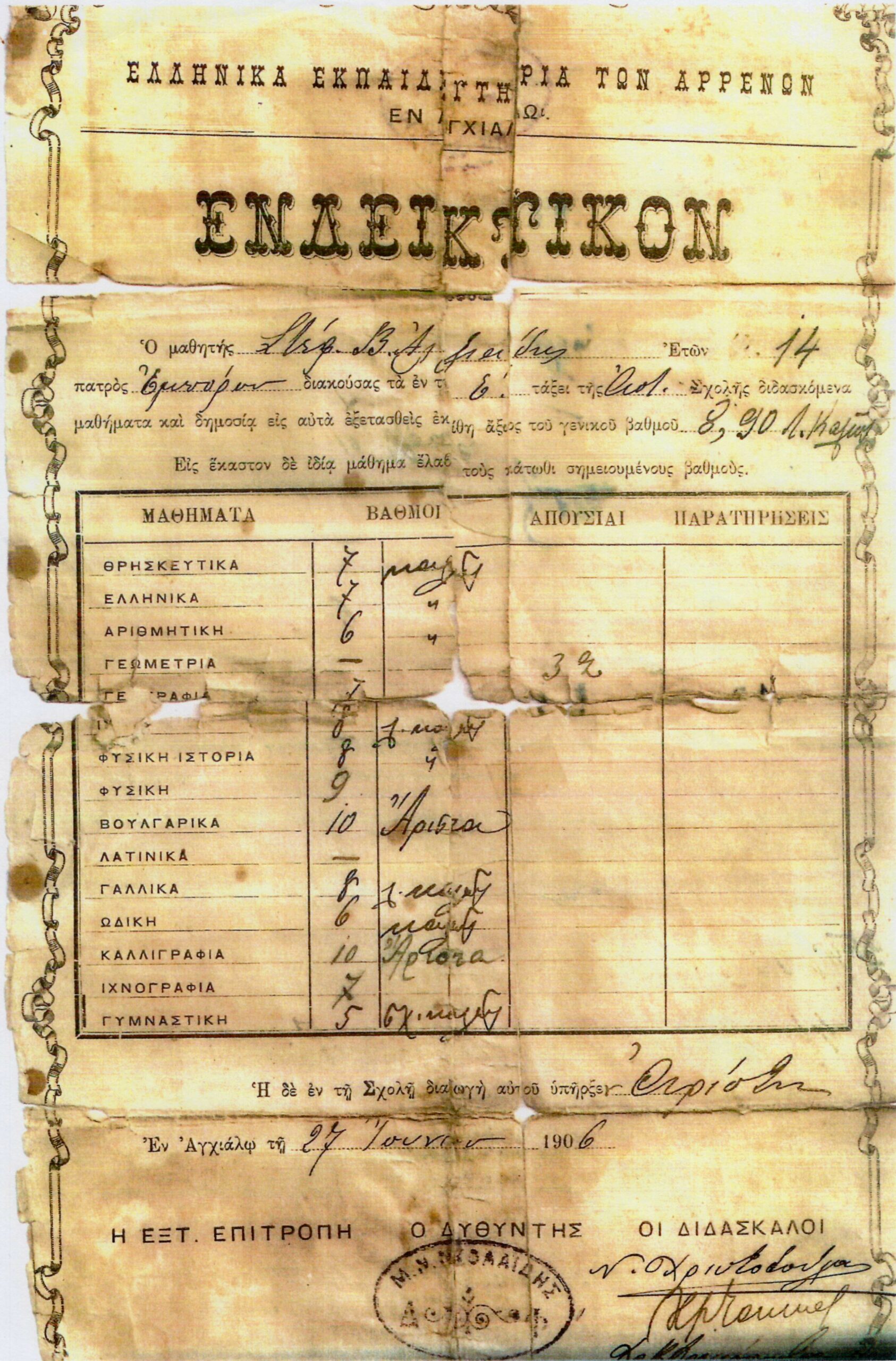

Mesembria was one of the most developed cities in Eastern Rumelia (<em>Roym–i–illi</em> = “the land of the Romioi”, while the official name was established by the Congress of Berlin in 1919) and one of the most important centers of Hellenism. It is mentioned by Suda as the homeland of the wise Aesop, who, according to Heraclides, “was of Thracian origin.” It rivaled in development and splendor the other major cities of Northern Thrace—Agathoupoli, Apollonia (or Sozopol), Pyrgos, and Anchialos. Together with Anchialos, Agathoupoli, Apollonia, and Varna (ancient Odessos), it formed the renowned “Pentapolis” of antiquity. It included the following villages: Agios Vlassis, Haemus, Bana, Aspros, Ravdas. The surviving refugees from Agios Vlassis have much to recount about their homeland, its beauty and vibrancy. Agios Vlassis was a purely Greek village, and its residents were engaged in fishing, viticulture, the timber trade, agriculture, and livestock farming. They had a church dedicated to Saint Athanasios and a school, where up until 1906 the teacher was Greek and instruction was in Greek. However, from 1906 onward, Greek was banned and teaching was conducted only in Bulgarian and only by a Bulgarian teacher, which is why the children were unable to complete school. They were, however, cultivated, hardworking, upright people, and of course, lovers of festivity. Their devotion to Greece led some of them, upon reaching adulthood, to stow away on ships departing or passing through Mesembria headed to Constanța and Russia, and from there to Piraeus. Some were even reunited with others when the rest arrived in Greece as refugees. When they speak of those places where they were born and first experienced life, they become enthusiastic, proud, and in their words one can deeply perceive the hope of their fathers—and their own—for return.

Certificate of academic performance belonging to Stefanos Alexiadis from Agios Vlassis, showing excellent achievements.

Karadza-Halil, Bana

The village was also home to three families from Karadza-Halil, a village near Basiki: the families of Christos Kopsalidis, Kroustalis Kopsalidis, and Apostolos Alexandridis. Additionally, three families came from Bana, a village near Agios Vlassis in Mesembria: the families of Alexiadis and Topakis.

Tepe Tsiflik

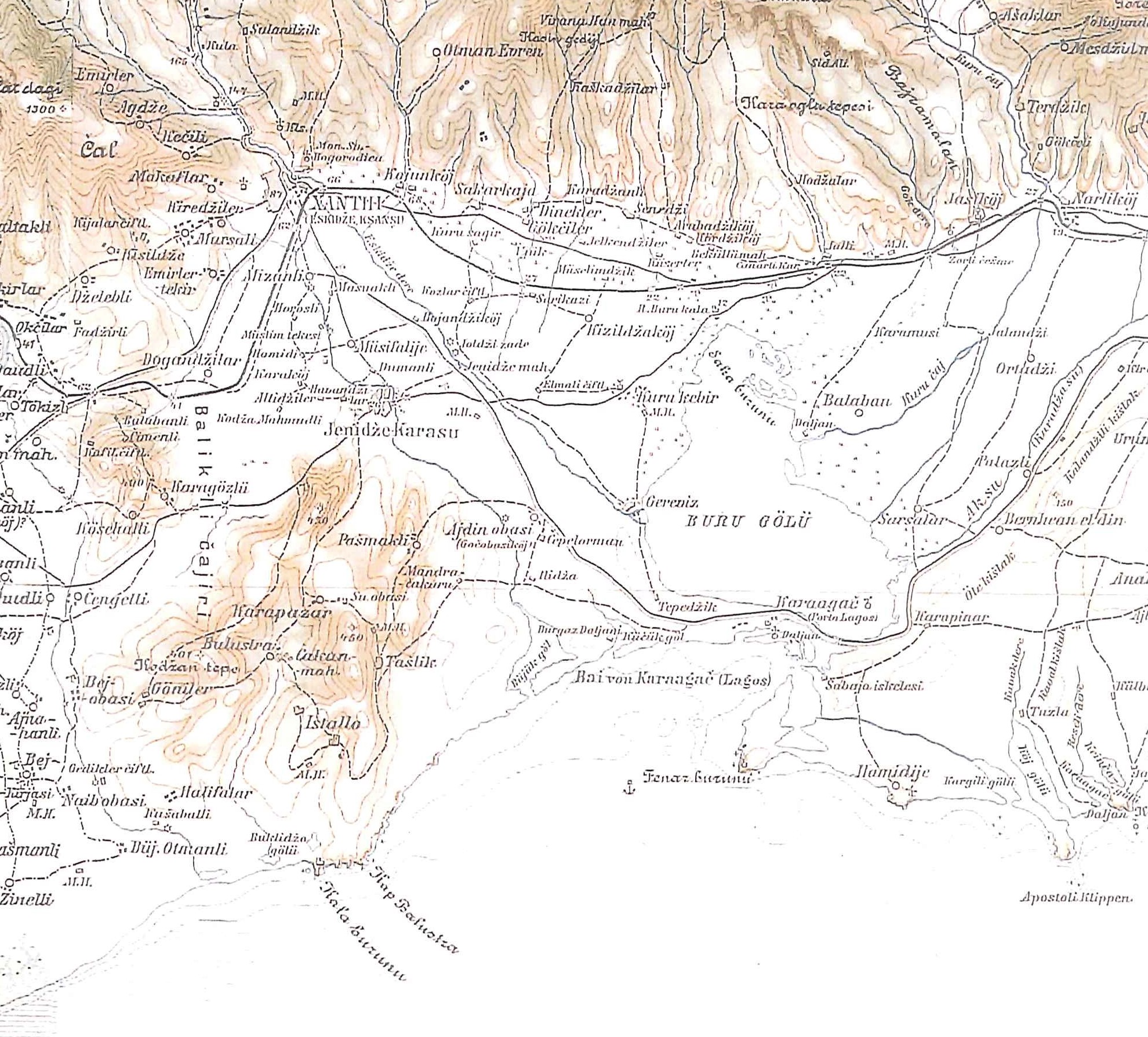

Section of an early 20th-century Austrian military map, showing Ottoman names of Thracian settlements. Tepe Tsiflik is visible below Lake Vistonida (Buru Golu), as is Selino (Gereviz) and Xanthi to the upper left, marked as XANTHI Eskidze.

This was the name of the place where the first Eastern Thracian refugees chose to build a new settlement and a new life. They chose it for its location near the sea and beside the lake, and because the prefecture of Xanthi, to which the area belongs, was a developed commercial and intellectual center, and the land fertile and favorable for the development of a new settlement. The name means “land ownership on a hill” and it belonged to a wealthy Turkish landowner named Hadji Ali Bey. There was a reference to Tepe Tsiflik in the newspaper “Fos” of Thessaloniki (as recorded by Mr. Thomas Exarchou in his book “Xanthi in the Dramatic Four-Year Period 1919–1922”). The issue was published on 14/08/1919, shortly before the liberation, and stated the following: “The (Bulgarian) komitadjis are very careful not to appear in the city where the French authorities exhibit strictness. The komitadjis therefore chose as a refuge Tepe Tsiflik near Yenidze – Karasoul (Genisea), whose mayor, Nikolaki Georgiev, is among the prominent chief-komitadjis of the area.” Tepe–Tsiflik thus belonged to a Turkish landowner, and because it had a forest next to it, it was a good hideout for rebels. About three years later, with the arrival of the refugees in Western Thrace and the urgent need to house them, the revolutionary government, led by Nikolaos Plastiras, with Decision No. 3473 of February 14, 1923, proceeded to the “mass expropriation of farmlands, estates, and communal lands.” Thus, Tepe Tsiflik became a refugee settlement and, in honor of the Black Rider, the benefactor of the Thracian refugees, Nikolaos Plastiras, it was named Plastiria.

1922 – 1940

At that time, Xanthi still belonged to the prefecture of Rhodope, as did our area. The first to arrive at Tepe Tsiflik were refugees from Eastern Thrace (who, as mentioned, had left their homes in October 1922), specifically from Bassaït and Kessani. Initially, they stayed for a while in tents provided by the army under the care of Plastiras himself, who, according to tradition, passed through the area, saw the desperate condition of the refugees, and approved funds for them to build houses and settle permanently — which is why the place soon took his name.

Gradually, however, the founders of the village arrived at the end of 1922 and throughout 1923. This was because, in their search for a new home, they initially stayed in other villages — for example, some from Bassaït first settled in a village near Alexandroupolis and then sent a few men to find a suitable place for permanent settlement. According to testimonies, three of them were Christos Kartalis with his son, also named Christos, and Giorgos Albanidis. That’s how they discovered Tepe Tsiflik. Others first stayed in Didymoteicho and Sappes, while some from Katikioi initially went to Feloni near Xanthi. However, the local community there did not welcome them, and they were later directed to our area. According to one account, there were initially 30 families from Bassaït and 30 from Katikioi.

The following is the testimony of Thanasis Mousikakis, who came from Katikioi:

“In October 1922, Eastern Thrace went into exile; we came to Western Greece. Some of our families stayed in Didymoteicho, in a Turkish village. There were three army regiments stationed there, intending to strike Turkey a second time, but the Great Powers did not allow it. We were poor children, orphans — the army gave us a little aid through the mess hall, and we ate. From there, after the month of August in ’23, some families left and came here, others went elsewhere. When we arrived here, Plastiras had built about 60 houses in the village. We were late arrivals and weren’t granted a house, so we spent two years in tents and huts made of reeds. Then we turned to farming. My mother and my sisters cleared the land so we could cultivate fields and survive.”

We therefore have clear testimony that by August 1923, several families had already settled in our area.

Another piece of evidence comes from an excerpt of an article from the newspaper “Fos” of Thessaloniki, in the issue dated 29/09/1923:

“For the settlement of farming and tobacco-producing families, special settlements are already being built, most of which have already been completed and handed over for use by the refugees in various parts of the countryside. Thus, in Plastiria (Porto Lagos), 75 houses have already been erected…”

It is evident that the article’s author tries to clarify the location by equating our village with Lagos. Nevertheless, the name *Plastiria* was already established and well-known.

In addition to the army, the responsibility for the fate of the refugees during the initial period lay with the so-called Refugee Relief Fund, which greatly supported the refugees throughout Thrace until the Refugee Rehabilitation Commission was established in September 1923. I suppose it also guided some of the first settlers toward the expropriated Tepe Tsiflik.

These first settlers brought with them the few belongings they had managed to save, such as livestock or a few gold coins, and made do with them — always holding onto the hope that they would soon return to the “homeland.” Still, they had to find some sort of shelter. The state provided the necessary timber, and with the means at their disposal, they made adobe bricks to build houses and escape the cold.

They worked together, tireless and persistent, in solidarity — once they finished the bricks and the house of one, they would start the next. They shared the labor, the materials, the hardships, and… a wall, because their homes were duplexes. Along the boundary of two plots, two homes shared a common back wall and a sloped roof and naturally belonged to different families.

These duplexes were single-story, and each house had two rooms and a fireplace for heating and cooking. The shared wall had a small window in the middle so that the two families could communicate and help each other by exchanging some of their few goods. Typically, a duplex was built by two related families.

The floor was made of a mixture of soil (red or black — lime soil was unsuitable), fine straw, and manure, which the women tamped down and tended to every Saturday. On top of this firm base, they spread mats and then woven rugs, which they would shake out to clean the house.

In their yards, they had the outhouse, a storage shed, the granary, the stable, farming tools, a garden, a chicken coop, or even the family business — a tailor shop, workshop, café, etc.

I assume the initial housing plans were based on a rough parceling of land made by the army when it assisted the refugees during those difficult early months.

The struggle for survival was truly heroic, given the poverty, suffering, and despair of displacement, and the barren lands that were difficult to cultivate with the minimal tools they had:

“You could see their faces emerging — dark, dry, seemingly withered by the very soil they wrestled with all day — faces that bore more than age or exhaustion or the toll of their very skin, a store of stubborn patience and bitter resolve, wild not like a victor’s, but like that of the defeated who never accepted the terms of the loss.”

(Niki Anastaséa, *This Slow Day Moved On*, Polis Publications, 1998).

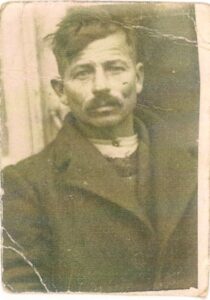

Grandfather Giannis Fylachtakis. The harsh conditions etched on his face.

The roads were gravel and traveling to Xanthi for essential shopping was a real ordeal. The few grocery stores sold only basic items such as sugar, salt, and soap.

As for water, apart from the lake, there was also a river. It started from the village of Paradeisos, passed through the area where the road that connects Xanthi to the village is today, after Genisea, and came to our village. It was a lifesaver, as it provided enough running water for drinking, washing, and watering the animals. Additionally, residents fetched water from a spring-pump in Porto Lagos. They would go there once a week with carts, fill one or two barrels, and meet their household needs with them. Before 1940, a well was constructed at the exit toward Selino.

Unfortunately, the lake and the river brought the scourge of malaria, which claimed many lives and persisted for several years. We know that in April 1926, a legislative decree was issued to establish the Association of Lowland Communities of Xanthi, which was tasked with carrying out water supply, transportation, and swamp drainage works in the communities it comprised. One of them was the community of Genisea, to which the village belonged since August 1924. Apparently, efforts were made to address the problem, but malaria continued to plague our fellow villagers until 1940. Touchingly, for many years the Thracians believed they would return to the “homeland,” but their hope was never realized.

At Christmas in 1928, the Eastern Rumelian refugees from Agios Vlasis arrived in Plastiria (as recounted by our fellow villager Thanasis Ekmektsis). They had left Bulgaria in October 1924. They traveled by ship to Constantinople, then to Alexandroupolis, Mesti, and finally to Strymi. There, they lived for a year in Bulgarian houses that had been requisitioned for the accommodation of refugees. Strymi used to be called Tsantirli, because the Bulgarians who built it worked as laborers on Turkish fields and initially lived in tents (tsantiria), before building houses. Their fields, which later temporarily came into the hands of refugees from Eastern Rumelia, were barren. The total of four years they spent in Strymi were very difficult. Yet the Greeks of Northern Thrace left their ancestral homes to build a new life in beloved Greece, and that gave them strength. They heard about Tepe Tsiflik from some who had passed through as soldiers or professionals, and they liked that it was close to a lake and the sea (because they loved the sea from their “homeland”), so they decided to settle here.

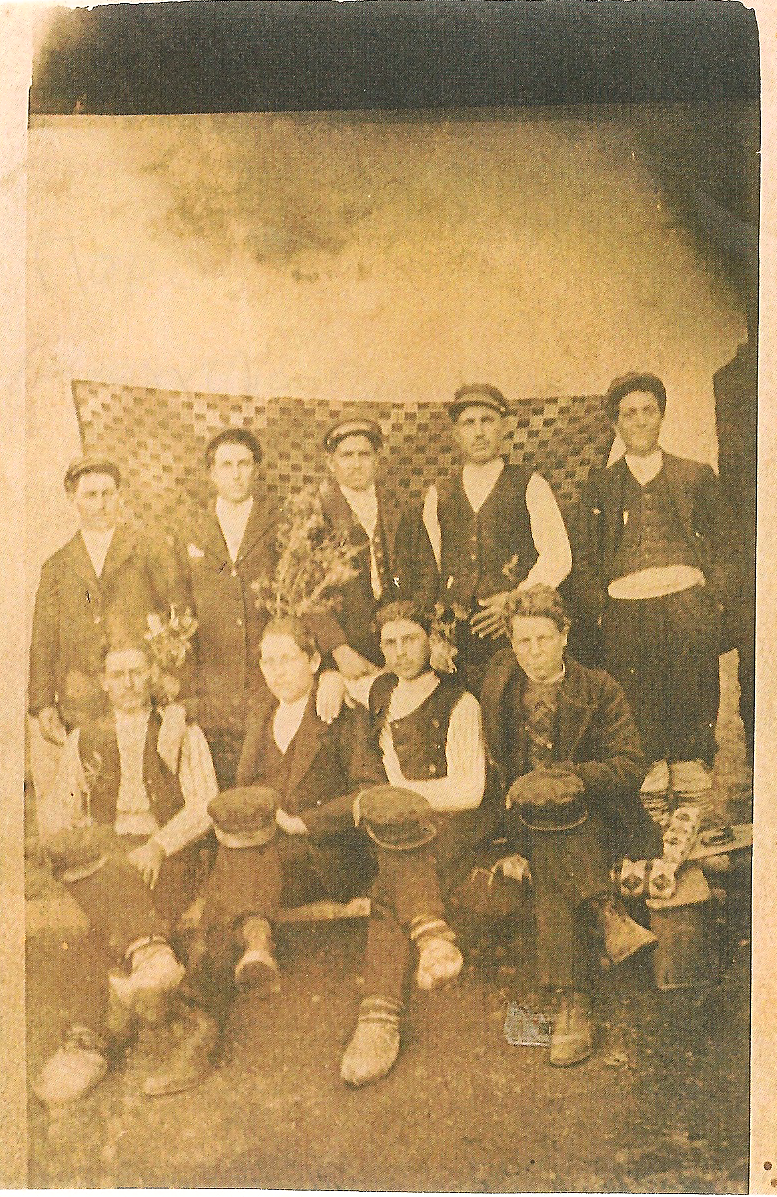

A group of young people from Northern Thrace on the Feast of the Annunciation, 1928.

Seated from the right: Tsatralis Fotis and Alexiadis Nikolaos.

Upon arrival, they found an organized settlement of Eastern Thracian refugees with duplex houses, grain and legume crops, two grocery stores, a small church (built by refugees from Basiki where the current water tower is), and 336 residents (according to the May 1928 census), who did not welcome them warmly, as they too would claim plots of land. In fact, the plots where they settled were suitable for legume cultivation, and when they were occupied, they provoked the anger of the Eastern Thracian refugees. Thus, along with coexistence came animosity. The Thracians called them Bulgars, while the Rumelians called the Eastern Thracians Turks. For about twenty years, there was intense friction, with them living in separate neighborhoods (mahalles), partying separately, and avoiding transactions and meetings. If girls from the Eastern Thracians approached Rumelian celebrations, their mothers would chase them away; the Rumelians, on the other hand, spoke disparagingly about the others. Moreover, because the Eastern Thracians were more numerous, they always elected their own village president, which displeased the Northern Thracians. The truth is that negative comments were muttered then and are still muttered even today. It is also true, however, that by the 1930s, the first “mixed” marriages began to occur, such as that of Dimitris and Eleni Tsamourtzis from Katikioi and Agios Vlasis, respectively. It was the need for survival and prosperity on the one hand, and their warm-hearted nature on the other, that softened the divisions and difficulties, so they could coexist productively and gradually turn Plastiria into a thriving village.

Characteristic and interesting is the description by N.K. Laios, a colonization officer, who in 1927 wrote:

“The rural Thracian, shepherd or farmer, is a calm and logical man, slow and serious with simple and regular habits. He gives the impression of a measured and stable person, which is typical of those devoted to the land. He judges calmly and coolly, thinks deeply, is hardworking and tolerant, but also stubborn… he lives conservatively… His relative, the refugee from Bulgaria, also reflects the true rural type, who lives by and for the land. He is almost identical to the Thracian, but more progressive, a seeker of progress, an agent of order.”

When the Eastern Rumelians arrived, they were 40 families. The state gave them a grant of 5,000 drachmas, and they built houses with adobe bricks, no longer duplexes, in the southern part of the village. The new houses were single-story, with the following rooms: the “chayat,” a spring living room; the wooden-floored “ondas,” the winter living room and the only room with wooden flooring, also used as a bedroom; the “ontatskak,” a small bedroom; and the old “nontas,” a makeshift room for all kinds of work. The roof was made with tiles from Serbia. The floor was covered with a mixture of water and red soil, which they renewed and tamped down every Saturday. On top, they laid mats and finally woven rugs. The yard had enough space for all the other known structures and the garden, as the house was located at the edge of the plot. Because they were intensely engaged in viticulture and wine production, some built cellars to store the wine, while the most skilled winemaker, grandfather Christakis Zafeiriou, had a barrel-making workshop and a cauldron for distilling tsipouro. The first house built was that of grandfather Vasilis Alexiadis. The rest of the houses were built based on the plan designed by grandfather Manitsas, grandfather Athanasiadis, and grandfather Vasilis Alexiadis (men of special prestige among the 40 families that arrived), according to which the colonization office finalized the village layout.

Making a living was difficult: “When we came here in ’28, we had nothing. We had nothing to eat. Those who had older children sent them out to work here and there, and they brought something home. In the summer of ’29, they would go to Gervez’ and dig” (testimony of Athanasios Ekmektsis). The early years of life were very hard.

Athanasios Ekmektsis with his wife and children.

However, the Eastern Rumelians brought new life to the village. A large proportion of them belonged to guilds of skilled artisans and gradually opened workshops and stores—new grocery shops, cafes, a blacksmith’s shop, a tailor’s shop, a cobbler’s shop, a cooper’s shop, etc.—raising the standard of living for all villagers. They also planted various fruit trees in areas that seemed barren, but their greatest contribution was the vineyard. They had brought vine roots from their homeland, their beloved plant, which was later cultivated systematically and intensively by all the people of Plastiria thanks to the initiative of grandfather Christakis Zafeiriou who had a barrel-making workshop and a still for tsipouro where Mr. Antonakis’ venue stands today. Of course, vineyard cultivation is not an easy job, especially back then, with poor tools (the mattock, the flat shovel), it was a laborious task.

Yet, the vineyard proved “richly generous” for our village—retselia (i.e., boiled wine with fig or pumpkin), petimezi, must pudding, must cookies, wine—all were excellent foods. Petimezi was the best sweetener in the absence of sugar, while for dinner they often ate wine with bread. During the Occupation, they ate mamaliga, a cornmeal porridge, together with petimezi. Wine (and later tsipouro) became the trademark of Plastiria thanks to its quality. After all, since antiquity and later by Orthodoxy, it was considered sacred. I remember a typical scene—one Easter, we celebrated at the home of uncle Thanasis Ekmektsis. Toward the end of the festive meal, our host took a jug and poured the remaining wine on the ground, “so the dead could drink too, today Christ is Risen!” That is culture, ethos, tradition!

In general, the years 1929 to 1932 were very difficult for Xanthi, with widespread hunger. There is information that during the 1930s, the Kosynthos stream caused flooding problems in the villages up to Lake Vistonida, although it is not confirmed whether our own village was ever affected.

Christos Kartalis with his wife, Giannoula (née Noikokyridi), both first-generation refugees from Eastern Thrace (from Basaït and Beyentikioi, respectively).

1931 was a very important year. Plastiria became a community together with Potamia and Porto-Lagos, with our village as the administrative center. The first school was built, and land was officially distributed to landless refugee families. The distribution was carried out by the Settlement Offices, organized by the Refugee Rehabilitation Commission. The General Directorate of Settlement for Thrace was based in Komotini. The agricultural plots granted ranged from 30 to 40 to 50 stremmas (Greek land measure), depending on the number of family members. However, for our villagers, these were mostly forest lands. Between Plastiria and Selino, there was a small forest known as Fatme-orman, as well as another one toward Koutso, which had to be cleared to turn into fertile fields. Their effort was truly heroic, as they struggled alone, without financial aid such as bank loans, and with minimal means. Eventually, in 1934, they planted many beans, wheat, squash, and watermelons and had their first harvest, which was indeed good, as the land was fresh and rested. The following two years also yielded good harvests. Unfortunately, the settlement authorities withheld a large amount as payment for the houses and fields granted to them. Some people paid off these debts with the compensation they received for lost properties in Eastern Rumelia, which they had declared before fleeing. The poor, who had no properties there and naturally received no compensation, paid from the money they saved through hard work. However, during WWII, their “debts” were forgiven. They were also granted two stremmas of vineyards. Later, some bought many fields and built up wealth. They also had livestock—cows, oxen, buffalo, sheep—grazed by herders paid by the owners, sometimes also with meals, depending on the number of animals each had. Something few remember is that in the early years, there was an additional tax on products transported and sold in the city of Xanthi. The tax collectors had a checkpoint outside the village cemetery and thoroughly inspected the carts going to Xanthi for taxable goods. This taxation likely ended before 1940.

Women in the struggle

Harvesting in Fanari. First is Argyris Malakis, then Fotoula (Stavrakara) Kartali, Themistoklis Blioumis, Anastasia Albanidou, Kostas Papazoglou, further back Athanasios and Maria Stavrakara, and last is Albanidis Paschalis.

The first spontaneous celebrations, mostly on weekends, began after the initial difficult years. The Eastern Thracians gathered in the square in front of the first little church, while the Rumelians gathered in the grocery cafés of Nikolaos Alexiadis and Stefanos Gialamidis to ease their hardships. The Eastern Thracian grocers were Stamatis Dafos and Georgios Peirounidis (though these were not cafés).

An event that demonstrates our village’s economic standing within Xanthi is that in 1933, the Court of First Instance was established in Xanthi, and the General Administrator of Thrace informed the presidents and secretaries of the communities that their contribution to its operation was mandatory. Specifically, our community had to contribute 6,400 drachmas out of a total of 325,500 drachmas for the entire prefecture—about 2%.

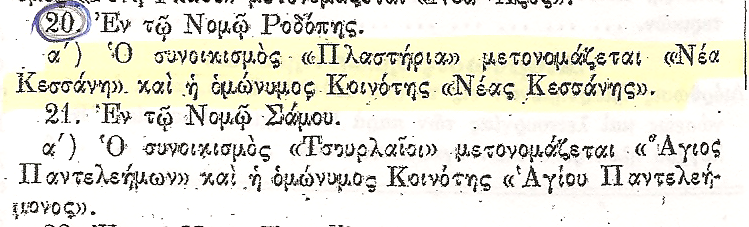

In 1936, the dictatorship of Ioannis Metaxas was imposed. As is customary in authoritarian regimes, opponents were persecuted, while favorable measures were taken for the rest of the population to gain consent. Thus, agricultural products began to be sold at higher prices, land debts were cleared, and in July 1937, construction began on the road between Xanthi and Porto-Lagos. All these were significant developments for the villagers, who justifiably felt grateful to the regime. Nevertheless, Plastiras opposed the new regime, so in September 1940, it was decided to rename Plastiria to Nea Kessani, to erase his name from the map of Greece. However, this became known and was implemented after the 1950s (details in the “Community” section).

1940 – 1950

In October, with the outbreak of the war, the enlisted men departed, but new residents arrived and settled in our village. They were Sarakatsani, who had previously moved from place to place ∙ however, with the war, the younger men were conscripted and their horses were taken. Thus, the women, children, the elderly, and those not called to battle were forced to settle somewhere permanently. Three Sarakatsani families stayed in Plastiria in huts they built in the neighborhood known as Gerveziotika. Many years later, they received land allotments and built homes in the village.

Giannis Tsiligiris with Kostoula and Maria Kiatipi, and his son Christos in Nea Kessani, 1947. From the book by Dionysis Mavroyiannis “THE SARAKATSANI OF THRACE, CENTRAL AND EASTERN MACEDONIA” Dodoni Publications, 1998

On April 6, 1941, Germany declared war on Greece and quickly broke the resistance of the Greek army, so by April 10 hostilities had ceased. On April 18, 1941, the Bulgarian ambassador in Berlin notified Sofia that the Germans had consented to the occupation of Thrace, except for a strip of land along the Evros river. The region secretly assigned to the Bulgarians by the Germans included Alexandroupoli in the east and extended west to the Strymon river and Lake Doirani. It was called “Belomorska Bulgaria” (Bulgaria of the White Sea – Aegean), with Xanthi as its capital. On Tuesday, April 21, 1941, the ragged and sorrowful Bulgarian army entered the city of Xanthi, marking the beginning of the second three-year Bulgarian occupation of Thrace.

Strict rules and prohibitions were immediately imposed ∙ the official flag, spoken and written language everywhere became Bulgarian, all Greek schools were closed (and reopened only after liberation), all Greek publications were destroyed, and street and store names were changed. Travel permits were required, and all weapons or military equipment had to be surrendered. Gatherings, leaflets, and movement from 10 p.m. to 8 a.m. were also banned. The behavior of Bulgarian troops would, they said, depend on the discipline of the local population. Our fellow villager Dimitris Fylachtakis was 11 years old at the time, working as a shepherd, and was often at risk of arrest by Bulgarian soldiers for returning late from grazing. Lastly, all churches had to hold services in Bulgarian, although in our village the Greek priest, Vangelis Tsolakidis, remained.

The Bulgarians quickly reorganized administration. Community councils were replaced with three-member committees composed of people with Bulgarian citizenship. Soon, a colonization effort began. Families from Bulgaria arrived and settled in the villages, occupying requisitioned homes. By early May 1942, 5,000 families had settled in the Xanthi area, 1,500 in the city and the rest in rural areas. In our village, tents were pitched for soldiers along the road from the village entrance to the current school, and houses were requisitioned for officers, along with any shops that had not already closed. The first school, built in 1931, was shut down and turned into a headquarters. Later, fortifications and bunkers were built in the Baira area.

Besides real estate, large animals—oxen, mules, donkeys, and horses—were also requisitioned “for the needs of the Bulgarian army,” usually without compensation. Greek producers of wheat or corn were allowed to retain only 100–150 kilograms of grain per person per year for family consumption. In general, Greeks suffered from hunger during the Bulgarian occupation of our region, although villagers, including those in our own village, were somewhat better off ∙ their entire harvests were requisitioned, their cellars emptied, but they had their gardens, chickens, managed to hide some grain in double-bottom barrels, and of course, they had Lake Vistonida, which saved them with its bountiful fish. It is moving to know that people from Xanthi came to our village—sometimes on foot—to sell their valuables for a bit of food. A short video (available on YouTube at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_XDc8Jz-iqQ) filmed by the Bulgarians in Porto Lagos is quite interesting—it was meant as propaganda to portray the region’s rich production and peaceful labor of the fishermen.

“Ntourdouvakia” or “ntourdouvakides”: In the Bulgarian language, the word “truda” means “labor” and the word “voinik” means “soldier.” The combination of these two words formed, in Greek, the word “troundovakia” or “ntourdouvakia,” which refers to a soldier—though not a combatant—but essentially a hostage of the Bulgarian army, a laborer in forced labor battalions, where many of our fellow villagers also ended up. Bulgaria needed cheap labor for some public works, such as road construction ∙ the easiest way was to conscript the occupied Greeks of Thrace, and so they did.

The 1941 draft class, born in 1920, had not served in the army. In April 1942, personal written conscription notices were sent for both the 1941 and 1942 classes. On May 1, 1942, about one hundred and fifty young men from the prefecture of Xanthi gathered at the railway station with a bundle of clothes, forced to be crammed into small freight wagons to travel to the Bulgarian countryside, to worksites like road building. There they lived in makeshift shacks under harsh conditions. They worked for 10 hours a day, with poor food, and if they weren’t young and strong, they wouldn’t have survived. None of them died from hunger, but lice, exhaustion, beatings, and the poor condition of their bare feet tormented them. Some were injured by landslides of rocks and soil. In fact, one of our fellow villagers (whose name is not mentioned by Thomas Exarchou, from whose book *Hostages of Bulgaria* all this information is sourced) was killed in a rock-blasting operation. In August they were granted a 20-day leave, and on October 14 they began returning to Xanthi. In 1943, even older Greek men were conscripted for forced manual labor. On May 27, 1968, it was announced that compensation would be paid to hostages from the period April 24, 1941, to August 28, 1944, upon submission of a relevant application.

Ntourdouvakia from Mandra and Avdira in 1942 somewhere in Bulgaria (photo source: f/b “Old Photos of Xanthi”)

The word “ntourdouvakia” entered our vocabulary along with other painful remnants from the harsh Bulgarian occupation and should be remembered by future generations, as it is an important part of our history. According to the list of hostage names, which exists in the book by Thomas Exarchou, the hostages from our village were:

Alexiadis Dimitrios

Albanidis Dimitrios

Vathrakeas Christos

Vathrakeas Christodoulos

Yalamidis Konstantinos

Karakatsanis Dimitrios

Karakatsanis Kyriakos

Karakatsanis Georgios

Kartalis Konstantinos

Menexidis Konstantinos (from Potamia)

Baraklianos Panagiotis

Myrtzakis Angelos

Stavrakaras Georgios

Stavrakaras Konstantinos

The word *ntourdouvakia* continued to be used even after the liberation and referred to forced laborers whom the Greek state now required to work without pay on various public works. This continued until 1967. Naturally, no one wanted to leave their work to become a *ntourdouvaki*, even for the homeland. The word was also used for laborers working on behalf of someone who could pay them.

Fortunately, our village did not experience tragic events during the occupation, such as executions that occurred elsewhere. The Bulgarian soldiers were, as expected, strict and often violent, as there were instances of beatings, and fear was present. However, they were not inhumane during their stay in the village. Some even had their families with them. After all, the villagers were peaceful and patient.

Similarly, they did not face serious problems during the civil war that unfortunately followed the end of World War II and the liberation. The people of Plastiria wanted and managed to stay out of the bloodshed and remain neutral. Only a few guard posts were installed by the national army, and officers handed out weapons to some villagers to stand watch ∙ a nuisance really, since no one was inclined to do so. Twice the partisans came ∙ the first time peacefully for supplies, while the second time they entered some houses more forcefully and demanded provisions, which they even promised to reimburse … when they took power.

Finally, for this period, it is worth mentioning that at the end of the 1940s two water tanks were installed, which were actually rolled into the village, so houses gained taps, and that in 1948 the first children from our village attended high school, which was of course located in Xanthi. The first to go was Vangelis Kopsalidis, who became a veterinarian, then Vasilis Alexiadis, who later became an engineer, Fotis Fotidis, who became a teacher and served in the village, and Apostolos Alexandridis.

Seated is Athanasios Tsamourtzis, while standing from left to right are: Nikos Tsolakidis, Thanasis Kampakis, the renowned teacher Dimitris Paliatsos, who helped many village children succeed, then Stavros Tsatralis and Apostolos Alexandridis.

1950 – 1970

It is said that in 1950 the village’s benefactor, Nikolaos Plastiras, visited the village and a celebration was held in his honor. This is most likely a myth, first because during the last three years of his life (he died on July 26, 1953), he was very active politically, so if he had the time and opportunity to make such a trip, it would have been more widely known, and second, because there is no photograph of this celebration, while we have many older photos documenting every aspect of village life. It is more likely that a celebration with Plastiras present took place before 1930, specifically in 1929 when Eleftherios Venizelos visited Xanthi, but these are, for now, only speculations.

Indeed, the twenty-year period from 1950 to 1970 marks the peak of the village’s prosperity. During that time, many public works were carried out, such as roads, the church of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross (in the 1950s), and the water supply system (in the late 1960s). It was also then that the renaming of the village to Nea Kessani was officially recognized and implemented.

The residents continued to work hard to make a living, but at least there were jobs. The port of Porto Lagos, the salt flats, the baths of Potamia, the farmlands, and the flocks of sheep, cows, buffalo, oxen, and pigs provided many job opportunities for the village’s young men and women. At the same time, many girls worked in fields not belonging to their families, usually in Gervezi (= Selino), on the estates of Memetakis.

To the right is Memetakis

Of course, we are not talking about well-paid or easy day jobs. For example, salt extraction was among the most profitable but also the hardest and most dangerous types of work. Workers also came to the salt flats from Mandra and stayed there, while workers from Xanthi were hosted in the village school.

Workers at the salt flats. The smiling man in the hat is Dimitris Fylachtakis.

There were also many shops ∙ cafés, all kinds of workshops, and grocery stores that fulfilled almost all the needs of a self-sufficient and thriving community.

In the grocery store of Nikolaos Alexiadis ∙ standing from left is young Kostas Alexiadis and Nikolaos Alexiadis. Seated from left: Eleftherios Vathrakeas, Theodoros Argyriou, Konstantinos Stavrakaras, and Gaitanis Eleftheriou.

School year 1955 – 1956

The sewing instructor with her students.

The population grew, and the old school was full of life. At the same time, for several years the Home Economics, Handicraft, and Vocational School “Greek House,” founded in 1938 by the folklorist Angeliki Hatzimichali under the auspices of the Ministry of Social Welfare, organized sewing classes in the village. A teacher would come to the village and teach the girls tailoring and dressmaking. In addition, children—mainly boys—who finished primary school had the opportunity to continue at the Gymnasium in Xanthi. There, they rented small rooms in pairs or trios, attended school in the mornings, and once a week received a package from the village with food ∙ bean soup, chickpeas, eggs, bread. With those, the worthy children who were determined to succeed in their studies grew up. Later, they managed to study at esteemed institutions and pursue successful careers either in the public sector, which needed educated employees, or in the private sector (though far from the village). From that time on, Nea Kessani began to produce many accomplished scientists (engineers, doctors, lawyers, educators, etc.), as well as skilled professionals.

However, some had to choose emigration in search of better work and living conditions, mainly to Germany and Australia. Indeed, many of our fellow villagers live abroad and maintain ties with the village, as much as circumstances allow.

In the 1950s, the football team “Diagoras Neas Kessanis” was also established, which not only managed to join the 4th National Division but also reached the championship final of the 1992-1993 season, where they played against the team from Genisea (the team continued competing until a few years ago, when it was unfortunately dissolved due to a lack of new players).

The legendary Diagoras Neas Kessanis team. The first goalkeeper on the left is unknown. Standing from the left: Zizikas Ilias, Kampakis Thanasis, Tsatralis Stavros, Eleftheriou Gaitanis, Peirounidis Vangelis, and Alexandridis Apostolos. Seated: Fotidis Vasilis, an unknown, Tsamourtzis Triantafyllos, Christoforou Giorgos.

At that time, Nea Kessani must have been one of the most vibrant villages in Xanthi prefecture, full of activities and festivities. In the winter, warmed by wine or tsipouro and a good fire, the men would gather and enjoy themselves in the cafés, while the women brightened their chores with evening gatherings. During the warm months of spring and summer, spontaneous celebrations would often take place after work in the village square or the local cafés ∙ at Stratís Christoforou’s, Stergionis the barber’s, and Fotis Gialamidis’ cafés, with Antonakis Ekmektzis’ joining later. Music was usually played on gramophones with large horns, which the two fierce rivals, Gialamidis and Ekmektzis, would even turn toward each other to spite one another. These were spontaneous, traditional feasts full of music, dancing, wine, jokes, matchmaking, games, and a carefree joy that is sorely missed today. It wasn’t that they weren’t tired from working the fields, tending animals, the port, or the salt flats, or that they had solved all their problems, financial or otherwise ∙ but they were strong, optimistic, embraced physical fatigue as it ensured their livelihood and a degree of self-sufficiency. Most importantly, they relished good company, connection, and celebration—carefree, exuberant, and joyful.

Conditions remained favorable even during the military junta of the colonels. While in Athens and other large cities, persecution, fear, and the restrictions of a totalitarian regime made life difficult for many (both dissenters and non-dissenters), in rural areas things were different. The cancellation of farmers’ debts, public works, economic growth that coincided with the junta years, and the absence of anti-regime action made this period rather positive for the residents of Greek villages, including ours.

From the 1960s onward, some of the original homes were demolished to build more modern ones with concrete. Most of these “new” houses are two-story, with a ground floor or semi-basement, often used more by the family due to its spaciousness, coolness, and functionality. It served as a storage area, space for family gatherings (Christmas, Easter, engagements, celebrations), and was the primary living space. The upper floor is somewhat more formal. Access is only from an external staircase, and an upper balcony is considered essential. The loom and hand mill disappeared, and the fireplace was replaced by a wood stove or central heating. Everything changed.

1970 – Present

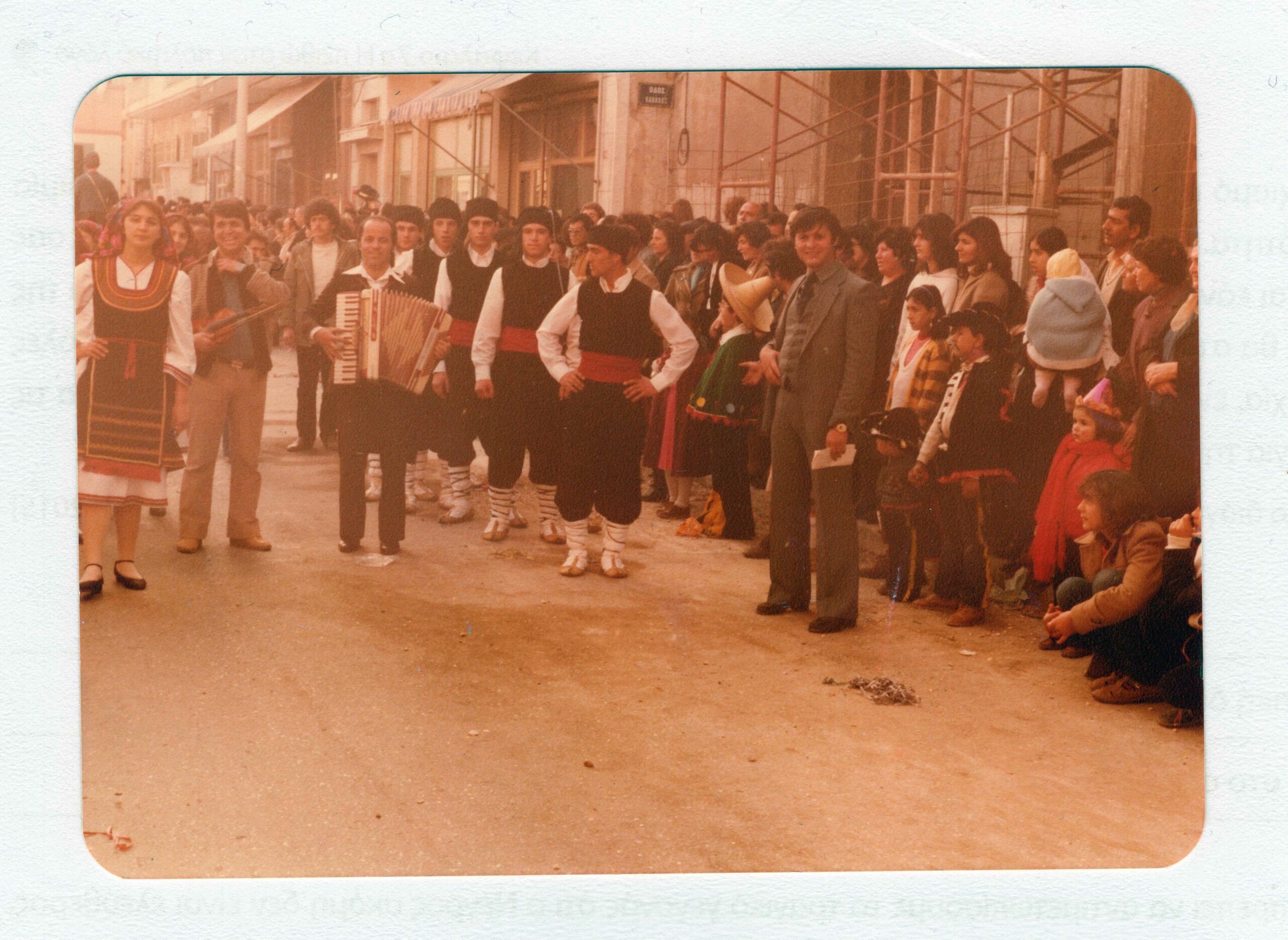

Youth from the former village cultural association at the Thracian Folklore Festival of Xanthi – 1970s.

The restoration of democracy (Metapolitefsi) found many from the village’s younger generation starting new jobs far from their family homes. Xanthi had by then become a growing city with numerous career opportunities and a vibrant life, drawing many people from all across the plains’ villages. Thus began the gradual abandonment of Nea Kessani by its youth. Those who stayed worked in agriculture and animal husbandry—difficult manual jobs that didn’t appeal to most. The village began to look deserted in the winter, especially on weekdays. Thankfully, on weekends, major religious holidays, and during the summer, it came alive with new families and children visiting grandparents and enjoying holiday time in the best place possible. In the summer, the village was revived with groups of young people having fun in the square. Every Christmas, Easter, and on other special occasions, wonderful feasts were held, filled with relatives, laughter, traditional dishes, excellent wine, and joyful grandparents. When the excitement grew, groups would take to the streets, visiting one another to extend the celebrations.

The period of abundance in Greece (1981–2000) brought financial prosperity to our fellow villagers both inside and outside the village and helped retain some young families, prompting the construction of our new and beautiful school in the 1990s. However, it has since closed due to a lack of children. The building has been renovated and maintained by the very noteworthy and active Cultural and Educational Association “Agia Paraskevi.” In recent years, newer residents (mostly temporary) include economic migrants from Albania (or Bulgaria), either alone or with their families.

Sadly, time has taken away from us our beloved grandparents—the heroic founding generation of our village—leaving only a few from the second generation as our comfort. Now, their sons and daughters have taken their place, keeping the village alive, maintaining their homes and gardens, passionately producing oil, wine, and crystal-clear tsipouro, organizing great feasts during the major local celebrations, and honoring the history of Nea Kessani.

Fortunately, since 2000, we see a trend among the third generation returning and settling in the village in newly built, beautiful homes, either having started a business here or working in Xanthi. This is a very hopeful sign. In fact, the economic crisis currently troubling Greek society might even have a positive effect if it leads more young people to appreciate the opportunities and value of life in the countryside.