Community – Church – School

History o fNea Kessani

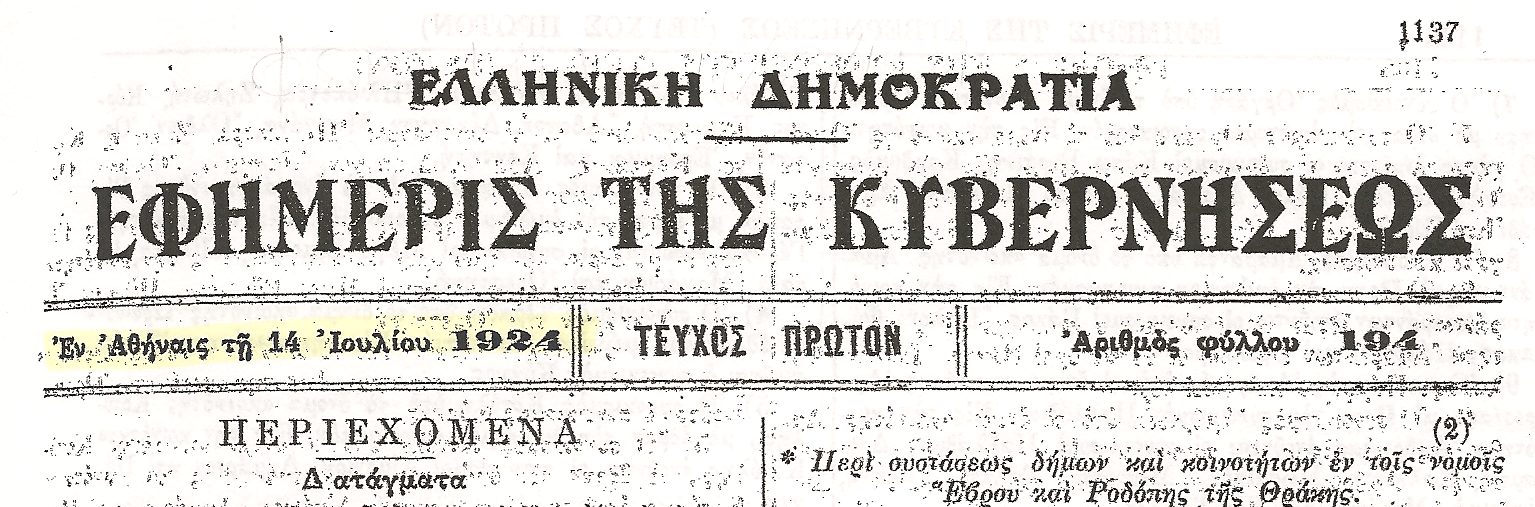

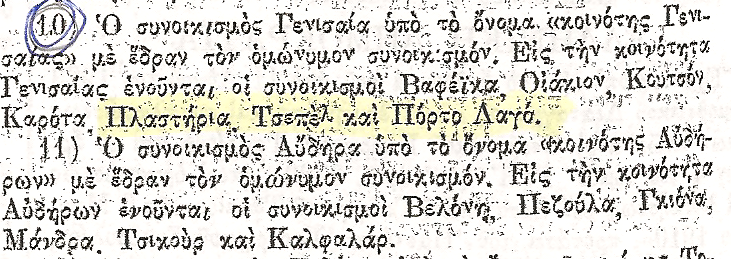

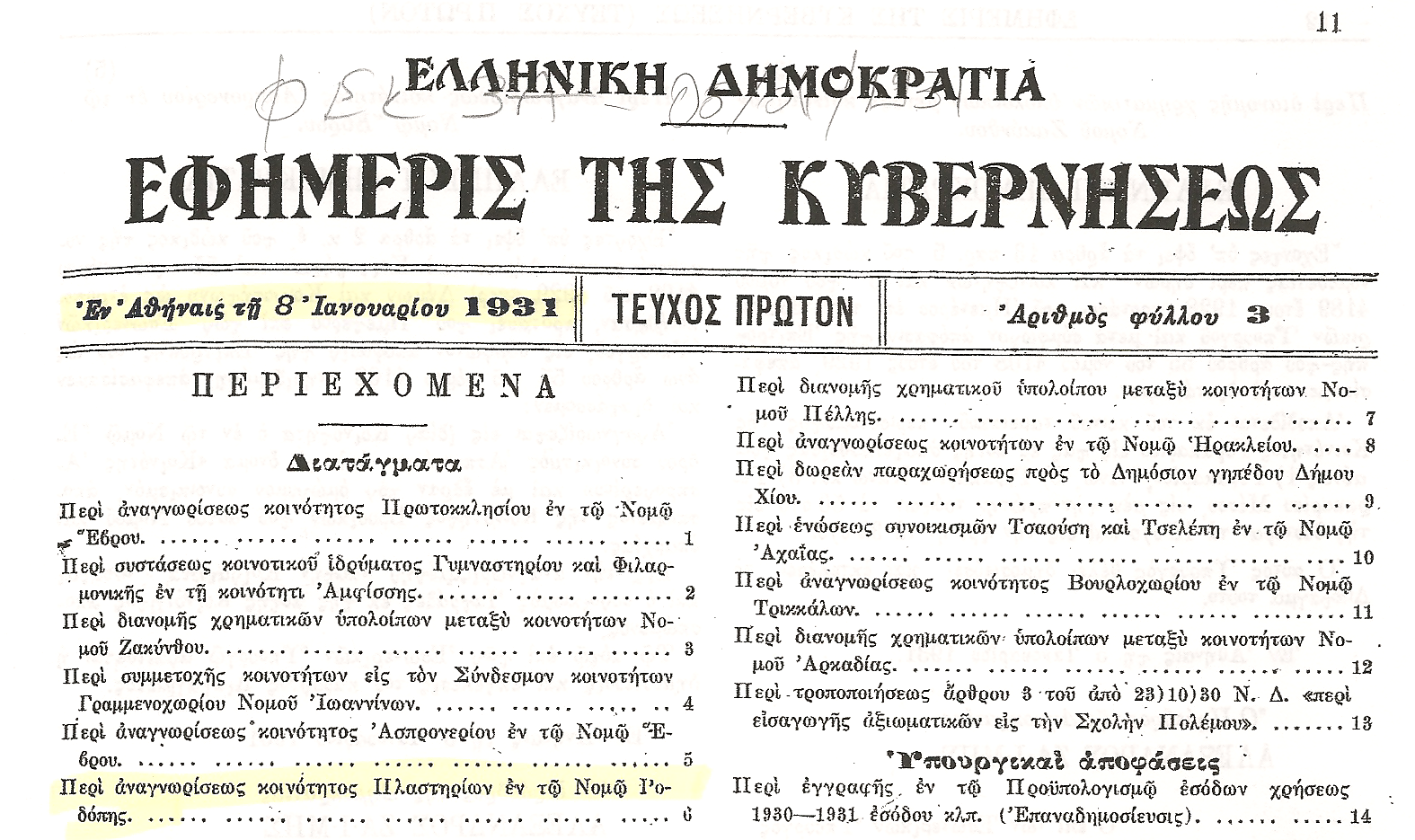

The issue of the name: Upon its founding, our village was named Plastiria in honor of the benefactor of the refugees, Nikolaos Plastiras. At some point, it was renamed Nea Kessani because some of its inhabitants were originally from Kessani in Eastern Thrace. However, even today it is still known as Plastiria, probably because the renaming did not have the support of all the inhabitants, many of whom had no connection to Kessani and continued to use the original name. In fact, while F.E.K. number 271A dated 03/09/1940 officially announced the renaming of the village, almost everyone confidently remembers that this change actually occurred during the 1950s. Moreover, in the 1940 population census, published in 1946, our village is recorded as “Community of Nea Kessani (Plastiria),” while on the military identity card of Stefanos Alexiadis, issued in 1947, it is listed as Plastiria.

There may be an explanation for this paradox: the 1940 F.E.K. changed the names of dozens of other villages except ours. We can observe that these were usually villages with foreign (e.g., Imamlár, Steveníkon) or very “common” names (e.g., Kasidochórion). These names needed to be changed into Christian (e.g., Agia Trias), ancient-sounding (e.g., Orestion), or otherwise more fitting names (e.g., Lefkochórion). However, Plastiras had openly and strongly opposed the Metaxas regime. What could have stopped this regime from stripping a refugee village of his name as a form of reprisal? Probably nothing. Unfortunately, just one and a half months later, World War II struck Greece, followed by triple occupation and civil war. These dramatic events, which consumed the entire 1940s, prevented the immediate implementation of all the renamings stipulated in the referenced F.E.K. and certainly the communication of these changes to the public — which explains why the people of Plastiria were unaware of it, and rightfully so. So, several years later, in the 1950s, the then community president, Ioannis Karamoussalidis, decided to implement the decision to rename the village. Still, as we mentioned, both names continue to be used to this day.

Of course, over the years, many things have changed besides the name. In 1997, under the Kapodistrias reform program, Nea Kessani ceased to be an autonomous community and became one of the four municipal districts of the newly established municipality of Abdera. The other three were: Avdira, Mandra, and Myrodato.

And since 2011, according to the Kallikratis reform program, it belongs to the municipal unit of Avdira in the new Municipality of Avdira. It is considered “new” because it was created from the merger of the pre-existing municipalities of Avdira, Vistonida, and Selero. Its administrative seat is Genisea, as the largest village, while Abdera has been designated as its historical seat.

The following table records the population development of our community:

| Census Year Settlement |

1928* | 1940 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 |

| Nea Kessani | 336 | 631 | 798 | 826 | 701 | 702 | 681 | 550 |

| Lagos | 196 | 266 | 488 | 498 | 420 | 424 | 372 | 394 |

| Potamia | 199 | 220 | 213 | 295 | 240 | 218 | 198 | 147 |

*This census was conducted in May 1928, that is, seven months before the refugees from Agios Vlassis of Eastern Rumelia arrived in the village and are therefore not included.

The presidents of the community and of the community/local council up to today (2013) are the following:

Before World War II

Karavetis Christos

Papantoniou Antonios

Karamousalidis Ioannis

Kartalis Christos

Blioumis Dimitrios

After World War II

Karamousalidis Ioannis

Kartalis Christos

Christoforou Christoforos

Albanidis Georgios

Galimaridis Savvas

Karamousalidis Ioannis

Kartalis Christos

Bourloukas Evangelos

Mazarakis Georgios

Karavetis Ioannis

Tsatralis Paraskevas

Dafos Konstantinos

Fotidis Fotios

Christoforou Georgios

Vathrakeas Eleftherios

Tsatralis Drakoulis

Kotsalas Nikolaos

Albanidis Georgios

Karakatsani Chryssoula

Mousikakis Iraklis

Mitrelis Konstantinos

Fylachtakis Alexandros

Drakos Christos

Dinos Georgios

POTAMIA, LAGOS, VISTONIDA: Since the establishment of the community of Nea Kessani, apart from our village, the villages of Potamia and Lagos were also under its jurisdiction, while our “lake” has been of crucial importance since the village was founded.

Potamia is located 18 km from Xanthi, on a bypass of the national road Xanthi-Komotini. It too was founded in the early 20th century by refugees from Asia Minor, whose customs differ significantly from those of Thrace. The inhabitants are mainly engaged in agriculture and livestock farming. The village church is dedicated to Saints Anargyroi Kosmas and Damianos, and the entire village celebrates on July 1st. Its residents are kind-hearted and hospitable people.

Potamia has hot springs that supply water to the Potamia Baths. The community of Nea Kessani attempted to make trial use of the geothermal fluid in a 6-acre greenhouse unit from 1987 to 1992. The otherwise ambitious program was not successful and the operation of the unit was suspended.

However, the thermal spring of Potamia is located in an area of great interest due to its natural and aquatic wealth and is considered of immense ecological importance. Its value was known since the time of the Ottoman rule, when patients would come for thermal baths. Modern free Greece was slow to discover it. As far as we know (making a leap in time), in 1945 the baths belonged to the contractors Germanidis and Adam, in 1978 to the Prefectural Fund of Xanthi, and since 1981 to the Community of Nea Kessani. In 1996, at the initiative of the then Community, the construction of a building with communal hydrotherapy areas was decided. It is a tourist complex of buildings that can fully serve a large number of visitors who are interested in the treatment of many ailments: inflammatory arthritis, degenerative joint diseases, chronic rheumatism, gynecological conditions, neuralgia, nephritis, allergic dermatoses, etc.

The operation of the Thermal Springs of Potamia has now ceased, but at one time it gave our region a breath of development and creation, since it was a destination for therapeutic tourism, where young people from the area used to work each year. [source of the above information was the website of the Municipality of Avdira]

Lagos, or Porto-Lagos (= the port of the lake) is located twenty-six kilometers from the city of Xanthi and serves as a center for the distribution of goods. The old national road connecting Xanthi and Komotini (the new one being the modern Egnatia highway, which bypasses it) is lined with dense groves of white poplars and passes through its houses.

In addition to its economic importance, Porto-Lagos is a visitor attraction thanks to the chapel of Saint Nicholas to the east – white, picturesque, built on a small islet connected to the land by a quaint wooden bridge, it appears to float miraculously. It is a dependency of the Vatopedi Monastery and is of great religious, historical, and artistic value. The interior of the church is of interest, particularly an icon of the Saint, a fine example of 16th-century Cretan art, as well as a stone built-in relief from the south door which also depicts Saint Nicholas.

A crucial factor for the local economy and development is the fishing activity in the lake with carp, mullet, and eels, in the coastal areas and of course in the renowned fish farms of Lagos. The eels, in fact, are exported to the Netherlands and Germany. A very interesting short video (which can be found on YouTube at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_XDc8Jz-iqQ) was filmed by the Bulgarian occupiers during World War II at Agios Nikolaos in Porto-Lagos to promote, for propaganda purposes of course, the rich production and peaceful work of the fishermen throughout the region.

Lagos is inextricably linked to the history of Lake Vistonida. In Byzantine times the area was called Poroi (poros = passage) and had a direct connection with Peritheorion. It held great strategic importance but was also a center of oyster farming and fishing. The Byzantines had named it “Poroi”. Over time it changed to “Porou”, then “Porou”, and during the Ottoman rule “Bourou”, referring to the entire lake along with the island opposite the small town of Porto-Lagos. The name “Porto-Lagos” was given by Italian sailors (Venetians and Genoese condottieri) and means “Port of the Lake”.

Of course, various factors deprived the place of its former glory. However, Lagos continues to be of great importance for the development of the region; the port has been dredged, and loading and unloading of ships brings notable activity. Every year on the Epiphany, the waters are blessed in a festive atmosphere by the Metropolitan of Xanthi, and the waterfront is bustling with people. In July, during Maritime Week, various cultural events take place, and on the final evening, during the sardine festival, the port fills with people who enjoy the stroll, the fresh fish, the plentiful wine, and the live orchestra. Finally, on August 6, the locals celebrate the name of their village church, the Transfiguration of the Savior.

Lake Vistonida is one of the most important wetlands in Greece and Europe due to the rare flora and fauna that thrive in it, which is why it is protected by the international RAMSAR convention. It is the largest lake in Thrace, covering an area of approximately 42,000 stremmata (10,400 acres), which varies depending on the season, while the three channels connecting it with the Thracian Sea at Porto-Lagos brackish its waters, making it one of the largest lagoons in Greece. Its birdlife includes up to 302 species (such as herons, purple herons, cormorants, swans, pelicans, geese nesting during their migration, etc.). On its shores live many animals, such as otters and badgers, and the silent world of its 37 species of fish is equally impressive.

For the residents of our village, however, it was always simply “our lake”. Women washed clothes, children played and bathed, men hunted, fished, and provided their families with the best nourishment during times when other places (like Xanthi) suffered from hunger, such as during the interwar period and World War II. It was also a place of forfeit if someone broke a promise or lost a bet. The other side of the coin, of course, was the nightmare of malaria, which afflicted and killed many during the early decades, but its benefits were greater and lasting.

Every year, the blessing of the waters on Epiphany is held there. Unfortunately, today our lake is threatened by pollution (urban wastewater, agrochemicals, industrial waste, garbage), the intensification of agriculture and aquaculture, and uncontrolled hunting. The situation is urgent, and we hope the authorities will take action.

SALT PANS

The salt pans have been a consistently important economic factor for our village. The opportunity to extract the valuable salt provided work for many years to our villagers and to many other residents of both the plain and Xanthi. According to tradition, our salt pans were known since the Ottoman period, although this is not confirmed. In Greece, during the 1840s, eight salt pans were in operation, while at the beginning of the 20th century there were 16, and during the Interwar period 25. Since 1996, eight remain operational, owned by the company Hellenic Saltworks S.A., among them the salt pans of Nea Kessani.

They cover an area of 900 stremmas (90 hectares) with an annual production of 5,000 tons. The work begins each year in March/April and stops at the end of October. As mentioned, the salt pans provided many day wages to our villagers. However, they were hard-earned wages. Salt extraction, for example, was among the most profitable yet also the most dangerous jobs. In the past, many people worked at the salt pans between August 15 and September 5. Workers also came from Mandra, many of whom stayed there, while workers from Xanthi were hosted in our school. The last jobs were in covering the salt with roof tiles — work only for the most skilled craftsmen. The worst job was that of the “laspas” (mudman), who had to clean the salt of mud and droppings. Today, of course, most work is done with machinery.

From an ecological perspective, salt pans — although largely man-made wetlands — hold great ecological importance, primarily because they offer food and shelter to various important bird species.

CHURCH, SAINT PARASKEVI

The village’s first church was small and built in 1923 where the water tower stands today, by the first refugees from Eastern Thrace, using “siazia” (mud and straw) and later adobe bricks. It served the religious needs of the village until the mid-1950s, when a new church was built, also dedicated to the Elevation of the Holy Cross, like the first one. The location for the new church was chosen by Christos Kartalis (a first-generation refugee from Basaït, Kessani), a leading figure in the village who served as president of the community and for years acted as cantor. The skilled craftsman Georgios Petsanis was the one who carved and placed the stones for the modern church, and the first ceremony held was the funeral of his father, Paraskevas. The church was recently renovated, and the bell tower was covered with decorative brick, with financial support from many villagers and even expatriates, making it truly beautiful. It celebrates every year on September 14, when a local festivity is held.

The priests of the village from its founding to today are as follows:

Evangelos Tsolakidis

Nikolaos Psaronikolakis

Stergios Dringas

Aristeidis Karavokyris

Evangelos Konstantinidis

Theofanis Boumpoukis

Nikolaos Pehlivanis

Georgios Iakovidis

One of the most beloved locations in Nea Kessani is the small chapel of Saint Paraskevi, situated to the northeast of the village, very close to the shores of Lake Vistonida. The chapel was built following a dream had before World War II by Grandpa Konstantinos Katsikas, in which Saint Paraskevi revealed to him the location of her holy icon. The icon was unearthed, and Grandpa Katsikas made a small makeshift shrine using a barrel. Occasionally someone would come to light the small oil lamp. Often, residents of Lagos would also come, saying they had seen the Saint in their dreams asking them to light her candle. Later, through fundraising efforts, a chapel was built, which unfortunately burned down in 1958, and a new one was erected. Only the icon survived the fire. I will dare mention that in a copy of a tax register from the Ottoman period, five monasteries in the region of Xanthi are recorded. One is listed as the Monastery of Saint Paraskevi, although researchers cannot identify it with any known existing monastery or church in our area. Could it be that this icon originated from that mysterious monastery?

On the feast day of Saint Paraskevi, July 26, a festive vespers service with the traditional offering of bread is held on the eve of the celebration. The women prepare “kourbani” — roasted meat with rice — which is shared with everyone, followed by a rich celebration in the village square. The head of the animal slaughtered for the kourbani is buried behind the church’s sanctuary. For some years in the past, it was not buried but cooked and eaten as well. A grandmother from the village of Sidini found out about this and walked all the way there to warn the faithful not to change the tradition, and since then the animal’s head has been buried as in the old days. Another tradition says that Fotis Yalamidis would sacrifice a lamb every year for the Saint. Some years he neglected this offering, until he saw the Saint in his sleep asking why he no longer brought her the gift, and from then on, he resumed the annual offering of a lamb for the kourbani.

EDUCATION

“In 1924, we entered first grade of elementary school. There was no school. In one room, we lit a fire on the ground, and the children — a few children — sat around it on the floor, holding books in their hands, with the teacher standing. Later, they made a makeshift church out of ‘siazia’, and we had lessons inside the church until 1930. I completed all of elementary school there. Sometimes we had a teacher, sometimes not, for various reasons. We learned the alphabet, let’s say — we wrote on the blackboard with chalk and on a slate with a stylus. That’s how we learned our few little letters.” Testimony of Thanasis Mousikakis, a refugee from Katikioi.

The second building used as a school for just one year was the home of Giorgos Vathrakeas. Later, a proper school was finally built in 1931, with stone foundations and brick walls from the brickyard in Potamia, called Tsepel. In that school, children were taught until 1991–92, when the new beautiful school was constructed. However, today it stands empty due to a lack of students. Fortunately, the building has now been renovated and maintained by the highly commendable and very active Cultural Association “Saint Paraskevi”.

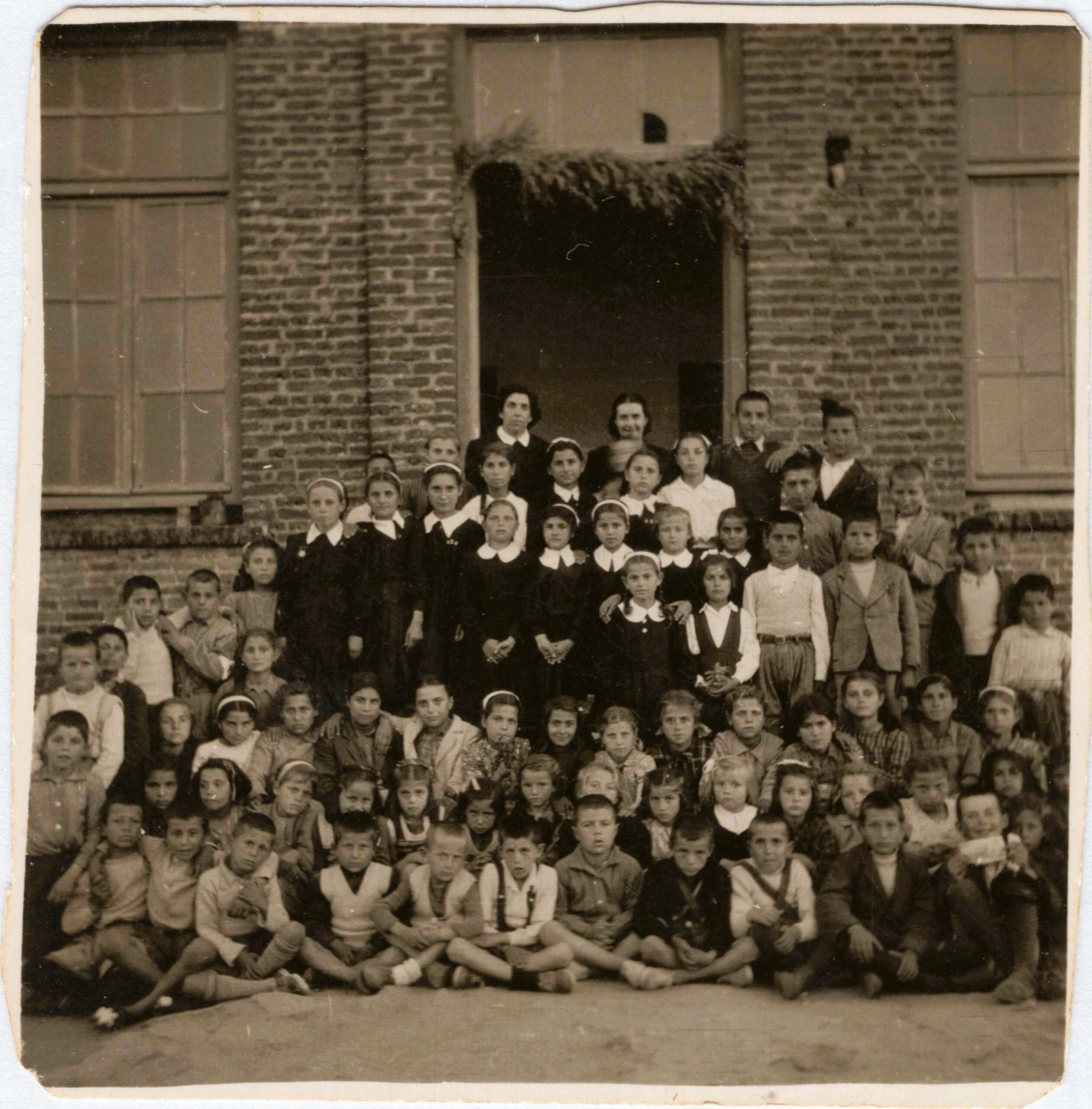

A wonderful photo from the old village school. On the left, the first girl in the lovely school dress is Fotoula Stavrakara, who years later became the wife of Dimitros Kartalis. Also, in the third row from the bottom, the third girl is Dimitroula Kartali and the tenth is Konstantinia Kartali (daughter of Zisis and Zoumboulia). Finally, in the front bottom row, the fifth child sitting, a blond boy, is Apostolos Alexandridis.

The President of the Hellenic Republic together with Thomai Koutaliou, President of the Cultural Association, in front of the new school. The children of the association wear traditional Eastern Thracian costumes.

School year 1948 – 1949

The school in 1955-1956