Customs of the Folk Festival throughout the year

History of Nea Kessani

1934 – Dancers

“Life is uncelebrated, a long road is unexpected.” We are a people with a rich tradition, because we have a long and rich history. The ancient Greek miracle, the Christian Orthodox faith, contact with peoples from three different continents, sometimes voluntary and sometimes (usually) forced and violent, Greek nature with its unique biodiversity and rugged landscape, our light and sea, the restless and inexhaustible Greek spirit, all of these have shaped a folk culture very rich in customs and festive events. Our folk calendar includes major and minor Christian holidays, local and pan-Hellenic, but also some that have been preserved (albeit with variations) from antiquity and prove the timelessness of our culture. Thanks to the fact that the rugged landscape greatly limited contact between communities throughout Greece in the past, but also to the fact that the Greeks were active in a much wider area than its current borders, from which they were recently violently uprooted, each place developed different customs and habits for each festive day throughout the year. This makes the work of each scholar and folklorist extremely interesting. The sweeping changes of our time require that these cultural treasures of ours be recorded as best as possible, because if we lose them too, we will be left completely empty.

In this chapter we will look at the customs of the popular holiday calendar throughout the year, starting with Christmas. I tried to record both the customs of the past, that is, those that our grandparents had in the “homeland”, Eastern Thrace and Eastern Rumelia, as they described them to me, and those that we maintain and observe today.

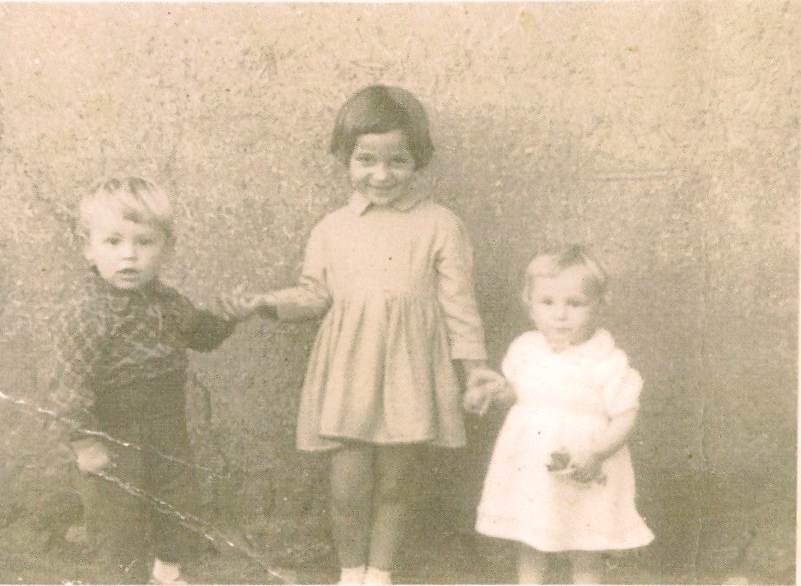

Tsolakidis Thodoros, Kynigopoulou Popi and Xanthi

25/12 Christmas

Christmas is the second biggest holiday in Christianity, after Easter. It is preceded by a forty-day fast during which fish is allowed until December 17, which is why it is considered a “happy” fast. When the day of the holiday approaches, children begin to prepare their groups for carol singing, as they did in the past. Back then, on the eve, the people of East Romulus sang carols from the evening, while the people of East Thrace sang them in the morning; today, all children sing carols in the morning.

Let’s first see how the people of Eastern Romulus celebrated ∙ the little children did not sing carols, but the young people from 16 to 30 would decorate themselves, gather together and start from the edge of the village to go through all the houses, sing, make wishes and receive the gifts, which were goodies, candies, walnuts, chestnuts, hazelnuts, carobs or cookies, but the most common were steaks from the pig that they had slaughtered for the holidays, which they would pass on a spit held by the children. Arriving at the door of the house, they knew that the housewife had the wick of the lamp down, they would start singing, the householder would listen to them and light the wick. They would bow down and say, divided into two groups:

“Christ is born

Joy to the world”

blessed,

the blessed, the glorified”

(and the other half)

“And as long as they go

and as long as they come”

“Christ is Risen”

The address “Christ is Risen” sounds strange ∙ it essentially states that in the ecclesiastical tradition the Birth and Resurrection of Christ are closely linked. Then they talked about the girl of the house, the boy, about his progress at school, about the betrothed, about the parents and the house, etc. The housewife, who had decorated the house with embroidered towels and paper decorations on the walls, and a festive tablecloth on the table, had a round bun (something between a tsoureki and a loaf of bread) ready to offer them. One of the lads was holding a small bag for the buns and as soon as the song ended he made a “meow” like a cat so that the housewife would understand who it was and give him the “baksis”. Then the householder would offer them wine with a wooden “kukla” and everyone would make a wish. They sang about him:

“We said on our day, let’s say about the master,

My master, on your bed a golden lamp shines

If you put oil on it, it shines on your master

If you put oil and a candle, it shines on the whole world “.

They kept these carols when they came from their homeland here for a very short time, to be replaced by what we say today. On Christmas Day, they would get up before dawn and go to church, decorated and happy, while someone, the grandfather or grandmother, would stay at home to prepare the table and specifically the kebab. Kebab is also called tigania, a delicious appetizer of fried small pieces of pork, which the people of Eastern Thrace also eat, but they call it jiz-biz. So, returning from church, everyone would sit around the table after the father had prayed and offered incense, and they would also eat kebab with lemon and drink wine. At Christmas, they did not make chicken soup or bampo, as in other parts of Thrace, they ate sweet pies with rice, zucchini, bulgur, cheese pies, sausages, meat, halva with flour, fruits and nuts. They celebrated for three whole days, without stopping, all together in the village cafe ∙ each one brought from his home whatever he could and they ate, drank, and danced tirelessly.

The Eastern Thracians celebrated in a similar way, with some variations: The children sang carols on the morning of the Eve and were given taliras or cookies. Unfortunately, I cannot quote the carols they sang in full, except for the beginning and the end:

“Christmas, Christmas, tonight Christ is born

born and nurtured but the world does not know it

both the world and the household and even the king ∙

born and nurtured with honey and milk,

the princes eat milk, the masters eat honey

…

As many stars in the heavens, goodies from the City,

may God give this householder so much good,

even if we sang to him, may God protect him

for Happy New Year.

On Christmas Eve, they slaughtered a pig, which they raised for this very purpose, and the neighbors gave them a few pieces. So in our village, we never had stuffed turkey, but pork. In the evening, the housewife would make the bampo, take the pig’s large intestine, wash it well and fill it with rice, liver, heart, and spices. Very early in the morning, after the festive service in the church, everyone would return to the warm, decorated house, where jizz-biz and raki or wine awaited them. They would also make stuffed chicken, eat at noon, drink and party until late.

According to our tradition, on Christmas Eve the goblins or karkantzaloi or karkantzelia appear. They come from the high mountains and the deserted land (not from the bowels of the earth, as in other Greek traditions) and their purpose is to cause damage and steal the pig from the householders during the twelve days between Christmas and Epiphany, when the waters are unbaptized. They only come out at night and woe to anyone they find in front of them, they tease them, drag them, climb on them, dance around them and especially if they are old. They are monstrous, their children go around barefoot and miserable, they enter houses and steal goods. At 12 o’clock at night the rooster crows and they say: “Which rooster crows? – The red rooster, let it crow and be happy, we still have time until morning”. Later when it is heard again: “Which rooster crows? – The black rooster, let it crow and be happy, we still have time until morning”. But at dawn: “Which rooster crows? – the white rooster, – ah, hurry, it’s dawn, they’ll catch us”. Then everyone runs away, the mothers put their children on their backs, take their donkeys and quickly return to the mountains, to come down again the next night. The myth of the goblins, which is pan-Hellenic, is probably due to the fear of the living for the dead and the jealousy they attribute to them for the Upper World ∙ so they come on the twelfth day, circulate among the living and disturb them, without causing any serious harm. The Lights disappear for good, when the waters are sanctified.

They did not decorate a Christmas tree, nor a ship, as elsewhere. However, it was a wonderful opportunity for the whole family, relatives and friends to gather, to wish, to express their joy and love. This of course happens today too, except that now we have the Christmas tree, we listen to many foreign Christmas songs and we sing the carols that have become established throughout Greece:

Good day, lords

And if it is your definition

Christ’s divine birth

Let me say in your mansion

Christ is born today

in the city of Bethlehem

the heavens rejoice

all nature rejoices,

in the cave

is laid

in a manger of horses

the King of Heaven

and poet of all,

a multitude of angels sing

Glory in the Highest

and this is worthy

of the shepherds’ faith,

from Persia

the wise men come

with gifts

a bright star leads them

without missing a moment…

In this house where we have come

may no stone be broken

and may the master of the house live many years.

1/1 New Year

I think that today we give much more importance to the arrival of the new year than in the past, and this is due to the influence of Western Catholic culture. In Europe and the U.S., New Year’s Day was always celebrated as a big secular festival, while for the Greek Orthodox, on the contrary, the religious celebration of St. Basil was important and less enthusiasm for the new year. On the eve, the children would start singing carols again in all the houses, and because the New Year’s carols from their homeland were quickly forgotten, they would sing about New Year’s Eve and Santa Claus, as they still sing today, for the necessary (food then, money now) gift.

“New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Eve

My thin incense

and at the beginning of our good year

church with the Holy Throne/dome.

First Christ came out

holy and spiritual

to walk on earth

and make us kind.

Santa Claus is coming

and everyone / and he doesn’t accept us

from Caesarea

you, noble lady

image base/glue and paper

sugar candy kneader

paper and squid

see also with pallikari

the squid wrote

and the paper talks

Sit down and eat, sit down and drink

sit down and sing

I don’t know any songs

I know the alphabet

so we can cut the pie.

And next year!

The family of grandfather Christakis Ekmektsis in Agios Vlassis, Eastern Rumelia.

The people of Eastern Rumelia, however, did not sing about Santa Claus. They had another custom called “Sourva”. Three children would take a branch, a dal’, from a skullcap and go to the houses. As soon as the householders saw them, they would open the door and they would greet them with greetings:

“Sourva, surva, surva

Good morning and good morning,

lots of wheat, lots of barley,

May the barns be full, many birds

lots of goats, many lambs … (etc.)”.

Then they would gently hit the grandparents of the house with the branch and say: “sourva, surva, surva, old bones” or

«Sourva surva, giro kurmi

giro kurmi, giro stavri

like silver, like skulls

and in time, sons, sons, sons, kind-hearted.»

Of course, the traditional Vasilopita was not missing. The housewife prepared it on the eve (as today), which was bread stamped with the seal of the service, or a savory pie with minced meat and the lucky fluori hidden. In addition to the fluori, the Eastern Thracians also put other small objects depending on the family’s economic activities ∙ that is, if they were farmers, they put a little wheat, if they were tailors, a thread, and livestock breeders put a few hairs on a piece of paper. They also cooked chicken, cabbage rolls, cabbage soup, and they also ate pickles, nuts, and fruits. In the evening, they would cut the king’s cake, in the middle of which they would place a candle. The father would cut it and name the first pieces in the name of Christ and the Virgin Mary, then the house (i.e. the good element of the house), the grandfather, the father, and the rest of the family members in order of priority according to each person’s age. The lucky person who found the coin would have good luck all year long and would light a candle in the church with the coin. If the coin fell on the first pieces, of Christ, the Virgin Mary, or the house, the whole family would be lucky. We do more or less the same thing today.

Before the festive meal, the father had to incense everyone present, the house, the warehouse, the stable (=dam’), the chicken coop. In fact, the people of Eastern Romulus used to burn incense on a tile, not in the censer ∙ and they would let the coals go out, to see if they would catch ash, in which case they believed that they would have bereket’, abundance, throughout the new year ∙ if they remained black, they would not have a good year. After these rituals, they would all eat together and set off for the cafe, where the whole village would party until morning.

As for the beliefs about New Year’s, they believed (and I confess that we still believe) that they would do all year round what they did on this day. Thus, on January 1st, they tried not to argue, not to cry, etc., but also not to lend money to anyone. The girls would put a piece of the New Year’s bun under their pillow at night, so that they would see in their dreams the person they would marry. On New Year’s morning, the mother would get up first, find a clean, beautiful stone in the yard and touch the head of each family member with it three times, so that they would be strong all year long. Then, she would feed the chickens and say: “many chickens, many birds, much wheat, much barley” etc., wishing good luck for the new year. Finally, on New Year’s Day, we all enter the house for the “good foot” with the right foot and preferably let a small child enter first. Breaking a pomegranate at the front door is another New Year’s custom that we say brings luck, but I confess that I don’t know how old it is in our village.

The Church of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross of Nea Kessani

06/01 Lights

The Lights are a “Theotrani” celebration, because they sanctify the waters and the goblins flee because they fear the blessing. Tradition says that the heavens open and any wish someone makes is fulfilled. Also, that with the blessing the sea becomes sweet and drinkable. The church imposes a strict fast on the eve of the Lights. In the past, “in the homeland”, children did not go out on the eve to sing carols. Only the priest would go out and bless the houses and fields (the first blessing). Later, in the new homeland, over the years they followed the custom of singing carols to children on the eve of the Epiphany and saying:

Today the Epiphany and the light of joy and sanctification.

Likewise the stars are lighted

and all the waters are purified.

At the foot of the Jordan River, our Lady the Virgin Mary

sits on a donkey,

wearing swaddling clothes, holding a crown

and begging Saint John.

Saint John, my master Prodromus

can you baptize me?

I bow and I will and I will prostrate

and I beg my Lord,

tomorrow I will ascend to heaven

to burn the heavens

and I will descend to the pit

so that you may be baptized in Christ,

to trample down the idols,

to trample down the groves,

to sanctify the fountains and the waters,

to sanctify the master and the mistress.

or

to ascend again to the heavens

to gather fat and frankincense.

We killed the rooster,

we found the lights,

give us our tip

let’s go to another door.

Second from the left is Christos Kartalis

On Epiphany Day, after the divine service, the entire village sets off with the priest, the hexapods and the icon of Christ for Lake Vistonida and the sanctification of the waters. The young people are ready to fall to catch the cross, the beloved symbol, because it is a great honor and blessing for whoever succeeds. It has happened that they have to break the ice on the surface of the lake for the brave ones to fall. The lucky one who catches the cross places it on a tray and goes through all the houses, for the villagers to worship and silver it. At noon, of course, the family festive meal and feast follow. Let us note that the consecration of the Lights is the holiest of all; we keep it for a long time afterwards as a healing means and to consecrate the home, the children, the estates.

07/01 Synaxis of John the Baptist/Saint John

Yiannis Fylachtakis with the suffering of being a refugee on his face

Yiannis Fylachtakis with the suffering of being a refugee on his face

In our village, this celebration was particularly honored and its customs are reminiscent of the baptism of Christ. Mothers would take the children outside and, despite the cold, would water them a little so that they would be strong. Also, newlyweds or engaged women would go from house to house and shower them while they feasted. The men, on the other hand, had the custom of pouring (mainly) wine on someone, to shower a friend of theirs, and the friend would pour more, to shower the first one, and so on, until the whole village would be soaked and they would even compete to see who would shower the most villagers. Once, they took the doctor in a cart and threw him into the lake by two young men for twelve kilos of wine. Finally, despite the sleet and the cold, they all threw a feast together, since everyone brought whatever snacks they could, sausages, pastourmades, cheeses, pies and of course plenty of wine and tsipouro, and thus the great and episodic celebration would ideally end.

08/01 Saint Dominic – Feast of the Babos

From left: Dina Mitreli, Panagoula Blioumi, Georgia the Babos, Fanio Blioumi, Giannoula Karamousalidou, Sofia Blioumi, Panagiota Papantoniou, Athanasia Ekmektsi, Machi Bourlouka, Zoe Pagonaki.

On the feast of Babos in 1979

Plastiria is one of the few villages in all of Greece that maintains the custom of “feminism”. It is a feast in honor of the most important woman in the village, the midwife, the one who freed women from the inevitable pain of childbirth and whose presence was necessary for the health of the mother and the baby. The name of the custom as “Babo’s Festival” comes from the Eastern Romulan idiom, where “babiden” means midwife. In Eastern Thrace, babo meant old woman, but there is no contradiction in this, since most of the time the midwife was elderly; the oldest woman is also the most experienced in the mystery of childbirth. Essentially, all women celebrate that day, since it is the only day of the year dedicated exclusively to them. That is why men are strictly prohibited from celebrating the day, they wear an apron and a scarf, take care of the children and do the housework. The custom has ancient Greek origins and specifically comes from the festival “Thesmophoria” – as Professor Georgios Megas, a Thracian, born in Mesimvria, informs us – which was a women’s and at the same time agricultural festival, during which women prayed for fertility, and from the “Aloa” which were celebrated in early January in Eleusis, where only women participated, who would return to the city drinking plenty of wine, laughing at obscene jokes and at the feast table where they ended up there were replicas of male and female organs, symbols of fertility.

In 2011 some of the worthy ladies of the women’s club.

From left: Fylachtaki Argyri, Alesta Athanasia, Karamousalidou Giannoula, Katsika Evangelia, the then president of the association, Ekmektsi Eleni, Malaki Petrini, Arvanitidou Asimina.

But let’s see how the first residents and founders of our village celebrated Bambo, as their daughters and ladies of the women’s association told me. From the day before, the women would prepare. They would warn their husbands to come back early the next day, to look after the children, and they would prepare snacks, such as loukoumades, pancakes and pies. In fact, one of the midwives would give a bottle of ouzo with a red ribbon to a girl (or a small group of children) and send it to treat all the women of the village and invite them to the feast the next day. So they would all set off together early in the afternoon for the house of the oldest midwife, the babo. They would carry a bottle of ouzo or wine as a gift, sweets, flowers, water, a towel and a bar of white or green soap, to wash the babo’s hands with. They would reverently honor the babo, who deserved it for the services she provided. Each woman washed her hands with the soap and water she brought, kissed them, did three penances and gave symbolic money. They did this so that the child would slip easily from the soap and that every birth that the midwife would undertake would be easy. In other words, it was a ritual with a symbolic and auspicious character. The midwife would also treat them and give them a sprig of basil. Then a pregnant or newlywed woman would take the jug, in which the midwife had washed herself, and throw it down; if she turned her face down, she would have a boy, if she turned her back, a girl. The ritual ended here and they returned to their homes to prepare the delicious appetizers for the evening feast, such as cabbage appetizers, pickles, pasturma, pies, sausages, pork, crab cakes, donuts, and good sourdough bread. They also milked the animals, did their chores, cooked, prepared the children, handed them over to their father, and after putting on their best clothes, each of them took the appetizers she had prepared (covered with the best towel) and set off for the celebration.

The appetizers were an important matter and they all made sure to make something exquisite. In fact, they would put them out on the windowsill to cool down, with the window open, so that the young men would pass by and “sniff” them, stealing them. An important element of the day’s ritual was the disguises (which were probably related to the ancient Greek roots of the custom) ∙ women disguised themselves and satirized people and situations. They dressed as a policeman or a doctor, professions inaccessible to women at the time, a newlywed girl or an old woman. We should note here that in the past there were three midwives in our village, but the oldest was at the center of the celebration. In the evening, therefore, they would go to the other two midwives to perform the custom with the soap and then set off for the midwife’s house, all the women together, forming a procession, usually dressed as men and sometimes with two-barrelled guns in their hands, symbols of male power and authority. They had with them the bagpiper, the only and inevitable male presence, since none of them knew how to play the bagpipe. They would advance rhythmically, almost dancing, following the rhythm of the music, with exclamations of joy, such as “iich”, “van”, “e,e” (perhaps a corruption of the ancient “euoi”, “evan”). Upon arriving, they would “tie” the bampo, that is, decorate it with a floral wreath on its head and a row of “grandfathers” (or otherwise chat-pat, i.e. popcorn) around its neck. They would take her and set off for the place where the feast would take place. This place was the village cafe, which had only been laid out with rugs so that it was empty and could comfortably accommodate the feast, or, if the weather permitted, the square. They had already brought there all the goodies they had made in the afternoon and plenty of sweet, home-made wine. The midwife, as an honored person, sat proudly on her throne like the queen-leader of the group and was surrounded by the elders. The rest were having fun as much as they could, as wildly as they could.

As we said, the custom comes from ancient Greek women’s fertility festivals and in all these festivals, which aimed at the “Genesis of people and fruits”, obscenities and depictions of the reproductive organs were allowed. Thus, our custom retained a certain orgiastic character in its subsequent course. That is, the women at this feast drank a lot, sang, danced, told wicked jokes and stories, laughed with all their heart, but also held anything that could resemble a phallic symbol, such as a long piece of wood, a leek, a bottle ∙ but now to satirize men and the “source”, in a way, of their power and not so much for the invocation of fertility.

It is no coincidence that the participation or mere presence of underage girls was strictly prohibited at the festival ∙ firstly, because on that day the father had to take care of the children and the mother had to have fun free from obligations and secondly, because the spectacle was “unsuitable for minors”. Of course, men did not dare to even approach ∙ their presence would desecrate the women’s festival and they would have to be punished. They would either be drenched or stripped naked, and in any case, they would not have a good time. When someone once hid in a closet to watch what was happening, they were discovered, stripped naked and forced to leave completely naked and drenched in the night and the cold. In 1974, the head of the community attempted to enter the area with the force of the police, but was chased away with sticks. The party lasted until late at night or even until the morning, when everything returned to its usual “patriarchal” rhythm.

Today, conditions and habits have changed∙ women give birth in hospitals with the help of professional midwives, men and women live more or less equally and have equally more opportunities for entertainment. Thus, we keep the custom of women’s rule, not because we need to free ourselves one day a year from the power of men and party, but because we love the tradition of our mothers and grandmothers, we love and honor this ancient and beautiful custom and we want there to be a celebration in honor of women and the fertility that only they bring as a sacred gift.

Thus, today a “babo” is defined and she is a lady from the women’s association of our village who enjoys the esteem of the others. Days before, the ladies of the club arrange with great care the formalities of the celebration, namely the food, the music, the invitations to the dignitaries, the preparation of the venue, etc. On the afternoon of January 8, they wear the traditional Thracian costumes, which the club has, and go in a procession, accompanied by music, to the house of the “bambo”, offer her trays with treats, she also treats them, dance for a while in her yard, make her sit in a decorated carriage and go singing and dancing to the K.A.P.I. venue, which is large and properly prepared for the celebration. Upon arriving, they all dance for a while in the square, along with the official guests with rows of patlakia around their necks, and enter the K.A.P.I. There, on a high stage, a reenactment of the custom is held, followed by food, drink and dancing. Now men and children are allowed, phallic symbols are absent and the presence of local authorities gives the day an official tone. However, everything is done with love and passion, we eagerly await this day every year, which has a resonance in the wider region, since a large number of people visit our village to watch and participate in the celebration.

A group of young people in Eastern Rumelia, at the beginning of the 20th century

1/2 Tryphon the Martyr

2/2 The Preacher of Jesus Christ

3/2 The Holy and Righteous Symeon the Theodochos

These three feasts in the first three days of February are significant for farmers and pregnant women. Saint Tryphon (or Tryphos) is the patron saint of viticulture, the main occupation of the Northern Thracians and their great weakness. On this day, a service is held with bread and holy water that is poured into the vineyard to make it blessed and fruitful. In the village of Agios Vlassis, there was a holy water of Saint Tryphon and on his feast people gathered, drank holy water, got wet and hung pieces of their clothes on the surrounding branches, so that they would be healthy.

On Hypapantis we celebrate the reception of Jesus by Saint Simeon in the temple of Jerusalem and on this day farmers and especially millers do not work. The next day, Saint Simeon is celebrated. They say that the saint “marks” the children of pregnant women who work or cut something on his feast day. Pregnant women cannot cut anything during the two previous days, which is why they have prepared the food they will need in advance. The belief in this belief is so strong that there are stories of such marked children.

“Tryphos rubs the bones,

the Virgin Mary shapes them, and

Symios marks them.”

Chrysoula Akhtari at the 1977 carnival

Chrysoula Akhtari at the 1977 carnival

Carnival

The Sunday of the Publican and the Pharisee, the Sunday of the Prodigal

The Sunday of the Carnivore, the Sunday of the Cheese Eater

“Now is the carnival

the feet have joy

and on Clean Monday

the birds take to the air”

In the past, Carnival in Nea Kessani, but also in the villages from which its inhabitants came, was not celebrated as it is today with masquerades, streamers, parties and parades. They didn’t even dance for several years. From an early age, children and young people up to the age of 18 would go around and collect all the old baskets, baskets, and baskets and gather them in the square. In the evening, after work, the whole village would gather in the square and set the baskets on fire. The children would jump over the fires and say: “Every flea on the beach”. At the same time, the adults would sing and dance:

“The King spoke,

the old women should get married

and the old women would dance like horses

they would dance and dance

they would dance and dance.

an old woman with a big mouth

cabbage

a man is cooking

kicking the pot

eat the dogs cabbage

drink the ducks’ drinks,

I’m going to get married.

Children were still involved in the game ∙ girls made balls out of cloth and played. Another game was tsapalak’ (the Eastern Thracians called it kopsitsa) ∙ boys and girls would line up in pairs, someone would clap their hands, so that the last pair would separate and run in opposite directions, the boy would chase the girl and once he caught her, they would go to the beginning of the line and so on. Mothers watched the young children playing and paid attention to their future brides and especially to those who had a boyfriend and went with him to tsapalak’.

An original and entertaining custom of the holidays was done at home, when family and friends gathered to eat and celebrate, they would hang a boiled and peeled egg from the ceiling, the children would gather underneath, with their hands behind their backs and try to bite the egg ∙ whoever managed to do it, without using their hands of course, won. On Tsiknopempti they would grill and have fun in the houses and they used to burn the corks of bottles on the edge and smear them on each other. In general, over the years and as the terrible difficulties of World War II and the civil war were overcome, the people of Plastiria began to celebrate Halloween more intensely, masquerading in improvised, comical costumes, dancing in the village streets and visiting the homes of friends and neighbors, to cheer them up and make them laugh their hearts out. Also, in the past, groups of carnivalists would come from neighboring Potamia with improvised camel effigies and perform the custom of “Camel” or “Tzamala” and stir up the village in a feast.

Among the men, first was Petros Kartalis, second was Dimitros Kartalis and fourth was Vasilis Blioumis. Among the women, Froso Papantoniou came first, Konstantinia Kartali second, then Vasiliki Topaki, Athanasia Blioumi and Stavroula Kopsalidou sixth.

On the Sunday of Carnival night, the housewives meticulously cleaned their utensils to eliminate any trace of fat or meat and threw away any savory foods that were there, in order to prepare for the strict fasting of Lent that would follow.

Clean Monday is the first day of Lent. In the past, at least, they considered the fasting of Easter Lent very important and everyone followed it strictly. On Clean Monday we eat fasting foods, bean soup, pickles, laganes, olives, fresh onions, tarama, halva and of course plenty of wine, the good that the people of Plastiria do not lack even during Lent. In the past, some women would observe a three-day fast, that is, they would not eat or drink for three days after Carnival Sunday. This three-day fast from food and water seems a bit excessive to us, but back then they considered it an honor and a blessing to observe it, unless of course someone could not stand it, in which case they would eat, because they considered it a sin for someone to faint from fasting. But God was then the only hope, the only doctor, and they deeply believed that, if they could endure this three-day fast, God would keep them and their families strong.

A custom brought by the Eastern Thracians and which was maintained until a few years ago, but which has been abandoned today, due to its peculiarity, was the hanging of dogs. They would put two stakes in the square, which they would connect with a rope, wrap it around several times, and put the dog in the loop below, let go of the rope, which would unroll and the poor animal would turn around several times, only to land helplessly on the road and run away dazed and frightened. They did this to have a good harvest, especially for sesame, and, according to another theory, to keep the village dogs from getting mad.

17/02 Saint Theodore

The customs of the Eastern Thracians and the Eastern Romylians for this day are different. The Eastern Thracian, therefore, a farmer would prepare a bun for each pair of oxen he had (if he had any), an offering, and boiled wheat, which he would take to church. Every morning he would get up, go to the stable and pass the bun through the horns of the pair of oxen, which, shaking their heads, would cut the bun in two and the ox that cut the largest piece was the lucky one. Then he would feed the bun to the oxen and the remaining pieces would be eaten by the family; the rest of the day they would eat boiled wheat instead of bread. The young men would go to the field and cut a thorn with a flowering shoot, which they would prune in the name of the girl they loved, at night they would put the thorn under their pillow and wait for it to bloom the next day, which meant that they would marry their beloved (it seems that men also had such divination methods). That same night they would gather and go back to the houses that had free girls and steal various things, which they would collect in the square, it was very entertaining, especially when the parents woke up, discovered that they were missing various things and then had to sort them out from the square. Even today we have the custom of stealing things from houses.

Since the revival of the cute custom in our village in February 2024. The things of the houses with the free girls are waiting for their owners to come to the square to pick them up.

But the girls also stole from three houses the first-born ∙ they took flour, salt and pepper, kneaded them while singing, made a bun and baked it in the ashes, then divided it among themselves and each one put her piece under her pillow, so that they could see their beloved and left it there for three nights.

And for the people of Eastern Romulus, Saint Theodore was the Saint of the girls’ luck. On the eve, the unmarried girls did not do any work, especially they did not take thread for spinning, because the Saint’s horse would get tangled in it and would not find their lucky one. At six o’clock, the girls all went together to the house of our newlywed, who had prepared a very salty bun, with flour from three other newlyweds. But until she made the bun, they would take a board and go to the nearest stream or river to the village and place the board like a bridge from one end to the other, they would close their eyes and walk over it without speaking, while they would often lose their balance and fall and the place would ring with girlish laughter. After this ritual, they would go to the newlywed’s house to get their salty bun, she would wait for them at the door with a cup of barley and a sickle in the animal manure. Before entering the house, the girls would take some barley, open a hole in the manure with the sickle, plant it and say: “This barley that I sow, may I reap with the one that I will dream of tonight.” Then they would go inside and the woman would give them the pieces of the bun, which they would put under their pillow.

01/01 March

On March (the day of the 1st March and the day of the 1st March), the people of Eastern Romulus would hang a red cloth on the door of their house, while the people of Eastern Thrace would hang a wreath of flowers and the first would say: “May Babomarta be good, may she not bring us bad weather”. Babomarta was (allegedly) a bad woman, a bad month, and that is why they would bring out a red cloth, not a white one, because otherwise they would have hail. They would also wear a bracelet made of white and red thread woven around their neck, finger, or wrist, so that they would not get tanned, and on their feet, so that they would not stumble. They would take him out when they saw the swallows and put him under a stone with ants.

25/3 Annunciation of the Virgin Mary and National Holiday

In addition to the established celebration of the national holiday and the honor of the Virgin Mary, in Nea Kessani there used to be the cute custom of the swallow. The children of the village would all make a swallow out of wood in the morning, attach it to an axle so that it would spin, and paint it so that it would be beautiful. With this game they would go back to the houses, even to the surrounding villages, and say:

“Proclaim great joy to the earth

Praise, heavens, the glory of God

Rejoice, gate, rejoice

Rejoice, holy Cross.

Dance of our Apostles

And we, the disciples

Let us go back to the country,

Let us go back to the country,

Let us go back to the kings

The figs in the handkerchief

The wine in the glass

I have a good teacher,

if he starts to beat me

and if he starts to turn around

Priests in the sanctuary from this year

and better than ever.

Amen»

or

«Evangelize the earth great joy

Praise, heavens, the glory of God

Flying swallow, flying and speaking

and not silent.

March, my good March

and cool April

you showed that miracle

and learned the letters

letters royal

and you, housewife

go into your cellar

and put your passions back

give me five eggs

five eggs for Lent

and next year»

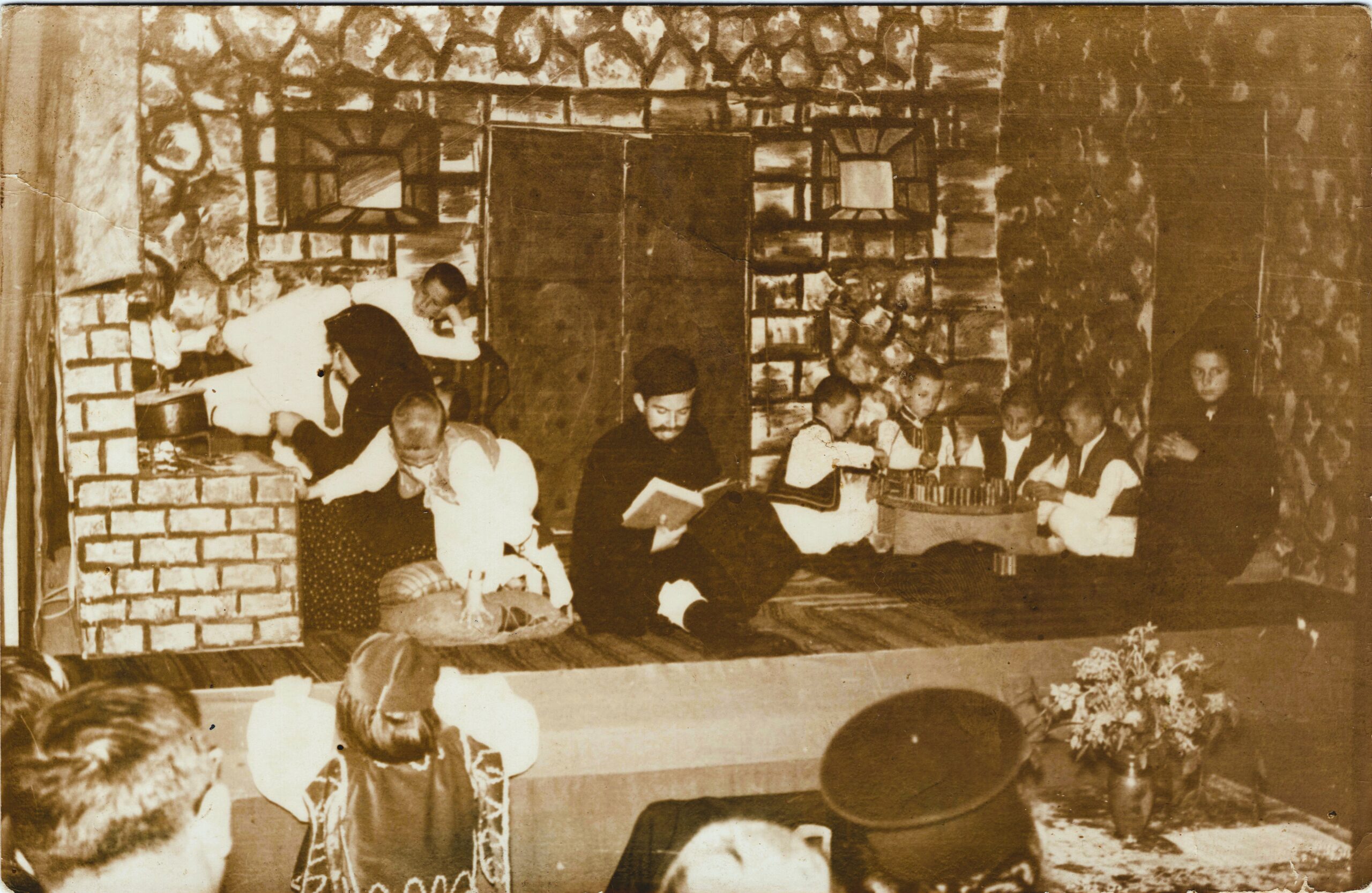

From an impressive performance that was performed by the legendary village teacher, Dimitris Psliatsos, with his students in honor of the anniversary of the National Revolution of 1821.

23/4 of Saint George the Trophy-bearer

The people of Eastern Romulus made a sacrifice on the day of the feast of Saint George. They baked it and distributed it with bread to three houses.

As in many parts of Greece, here too on this day they made a swing ∙ young men and women would find a large tree and tie a beautiful swing, with flowers attached to its ropes ∙ any girl who climbed up was forced to say the name of the one she loved, because from below another would beat her with a vitsa (thin rod) and would not leave her alone unless she confessed. At the end of Agios Georgios, everyone, young and old, would be “weighed” (=weighed) on the village’s only scale, to see how many kilos they had lost or gained since the previous year.

The women of Eastern Thrace would again perform the “klidona” ∙ a girl would silently take water from the well, that is, she would take it without speaking to anyone, neither on the street nor at the tap, which she would pour into a small earthen jar and the unmarried girls would put their rings and bracelets inside. They would lock the jar, leave it all night under the stars, and in the morning they would gather, open it, and take out the jewelry one by one, reciting verses.

Easter 1953: Outside Nikolaos Alexiadis’ grocery store and in front of the Cooperative’s warehouse, villagers from Ai Vlasis and Bana gathered to honor their good friend Stergionis Petsanis who had come to visit the village after 23 years. Seated (from left): Kiosses Pantelis, Ekmektsis Stefanos, Michaelides Eleftherios, Kampakis Panagiotis, Petsanis Paraskevas, Alexiadis Stefanos, Christoforou Athanasios, Baraklianos Georgios, Dimitrakopoulos Ioannis ∙ standing: Kiosses Stergionis, Michaelides Stefanos, Karakatsanis Kyriakos, Eleftheriou Sterios, Tsatralis Fotis, Baraklianos Giannis tou Georgiou, Petsanis Paraskevas, Petsanis Georgios, Topakis Paraskevas, Christoforou Giorgakis, Ekmektsis Georgios, Petsanis Stergionis, Ouzounidis Fotios, Peirounidis Vangelis, Ekmektsis Demetrius.

EASTER

The greatest celebration of Christianity, the foundation and quintessence of Orthodoxy. For the Greeks, it has a double symbolism, since it also signifies the sacrifices, passions and resurrection of the Nation, after the Turkish rule and the heroic revolution.

It is a movable celebration and is preceded by a fifty-day fast (it is called forty-day because in the past it was indeed forty days, and that is how the term was preserved), which was once observed by everyone, except perhaps children, who naturally could not stand it. It is celebrated on the first Sunday after the full moon of the vernal equinox. The faithful participate in the events that we honor with the celebration during the Passion Week that begins with the Saturday of Lazarus and Palm Sunday.

Lazarus is one of the most sympathetic religious figures for the Greeks ∙ his friendship with Christ, his stay in Hades and especially his miraculous resurrection by the God-Man move us. Lazarus was the man who saw what follows after death, but he kept it a secret from all humanity. The only thing the world knew was that he never smiled, so horrible were the things he saw in the underworld. Only once did he sneer, when he saw someone stealing a clay jug and said: “One piece of clay steals another”, so says the tradition. In Nea Kessani on the Saturday of Lazarus, children were once again the protagonists of the custom. Groups would gather and go around the village singing “Lazarika”. They would take a broom, put a head, hands, and clothes on it, so that it resembled a human, Lazarus, and on top of that a white cloth, which of course symbolized the shroud. So with Lazarus in hand, they passed through all the doors, singing and giving them eggs, sweets, etc. (something like carols, that is):

“Lazarus has come, the lambs have come

Sunday has come when they eat fish.

Get up, Lazarus, and don’t sleep

Your mother has come from the city

brought you paper and rosary beads.

Write Theodore, write Dimitri,

write lemon trees and cypress trees.

Where were they? Lazarus, where are you?

I was on earth, hid,

now I have come out and live, poor man

black sky, cracked.

Your hens also lay eggs

and your nests cannot hold them

give us to enjoy them too

next year too!

On Palm Sunday we celebrate the triumphal entry of Jesus into Jerusalem. Exactly one week before the Jews cried out “Aron, aron, crucify him,” they sang “Hosanna! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord,” and spread laurels in His path. The church is decorated with laurels (or laurels); at the morning service the faithful share them, to keep them on their iconostasis to burn in the censer in a difficult moment. In Eastern Rumelia, boys and girls took the laurels to the fountain and sprinkled them. If there was a river nearby, the girls would go and throw their yams into it; whoever’s yam went the furthest would become “kumbara”, that is, she would set a table for the others, while they would sing:

“Whoever goes first will be the bride

she will be the bridegroom.”

Holy Week begins, the most devout week of the year, fasting becomes stricter, songs are forbidden (as is the case throughout Lent), the atmosphere is heavily mournful, work almost stops and everyone watches with holy sorrow the passions of the Lord, as they unfold in the services of each day. The only work allowed is to prepare the house for the holidays and only during the first few days. On Holy Thursday we do not work at all. On Good Friday we do not work until noon at 12.00 when the bell rings for the ceremony of the Deposition. On Holy Saturday we are allowed to make the final preparations until the afternoon. On Holy Wednesday we bake the tsoureki in the morning and in the afternoon the anointing takes place, where the priest crosses the faithful with oil, for blessing and health. In the past, they did not anoint the faithful with oil in homes, unlike today.

On Holy Thursday the main ceremonies and events of Holy Week begin. Housewives dye eggs red, but also yellow, blue, green (at least for the people of Eastern Romulus), in all the colors of the rainbow, with purchased dyes. In the past, they used to knead buns, while today they use buns, which were decorated with red eggs and almonds. In fact, these Easter buns were simple, they did not contain milk or eggs. They were made by godmothers for their christenings in the shape of a doll for girls and a horse for boys. They made the doll’s body triangular and placed a white boiled egg on the head and a red one on the body with its arms crossed over the egg. For the horse, they started the dough with a sigma, then opened a mouth and made bridles, placed the red egg and it was ready for baking, without brushing it with egg. They also prepared a bun with a red egg in the middle, which they took and broke in the vineyard, for good luck. These were the things that housewives from Agios Vlassis did. Otherwise, they made a simple bun or a basket, which they decorated with 5-6 red eggs, as well as a bun with an egg in the middle, to break on the vine. The water with the paint that they had dyed the eggs was either poured on the root of a flower in the house (Eastern Thrace) or kept for seven Thursdays afterwards, during which they also dyed eggs, such as on Holy Thursday (Eastern Rumelia). Some, mainly women, fasted for three days from both food and water, on Holy Thursday, Holy Friday and Holy Saturday until Easter. If they were in mourning, they did not dye eggs on Holy Thursday or they dyed them black.

In the evening, the church plays “Today He is Hanging on a Tree” by candlelight in an evocative atmosphere, as the priests, cantors and children turn the cross around the church in a reenactment of the ascent to Golgotha and the crucifixion. The rest of the night until morning, the women of the village keep a vigil for the dead Christ. At the same time, the girls decorate the epitaph with various flowers or, as in the old days, with the “tear of the Virgin Mary”, as the dakrakia, the white hyacinths, are called, which grew on the banks of the river and in ditches and filled the small church with their sweet aroma. Waking up Christ, the women dressed in black lament:

“Today is a black sky, today is a black day,

today everything is sad and the mountains are sad

today the wicked Jews fired shots

to crucify Christ, the King of all…

(follows an extensive description of the Passion and how the Virgin Mary experienced it. It ends with Christ’s promise to his mother: )

… Only on Holy Saturday, around noon

when the rooster crows, the bells ring

the Lord signifies, the earth means, the heavens mean

and Hagia Sophia with three golden bells means

then mother I come with you, may you have great joys.

Whoever says it is saved and whoever says it is sanctified

and whoever listens carefully will receive paradise

paradise and incense from the Holy Sepulchre.

This song has many variations, but they all have common characteristics: the narrative character of folk parables, the intense emotion, they present the holy figures in their most human and painful dimension and mix the evangelical narrative with popular imagination and tradition. For example, they involve a fictional episode with the gypsy, which comes from folk tradition and which explains the way of life of the gypsies, since their distant ancestor supposedly received the curse of the Virgin Mary, because he maliciously made five nails instead of three for the crucifixion of Jesus. The women sympathize with the beloved Mother of Christ, they cry with her and indeed nothing is done hypocritically, the atmosphere is mournful and devout.

At the Crucifixion they hang embroidered handkerchiefs and shirts (votives) for health. In Eastern Rumelia, the gifts given to the Epitaph, towels, socks, handkerchiefs, embroidery, whatever everyone wanted, were put up for auction and the money was kept by the church for the poor.

The Epitaph in the church of Nea Kessani, in the Holy Church of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, on Easter 2024.

On M. On Friday they would go to the vineyard until the bell rang for the removal. In the afternoon, as is the case today, the procession of the Epitaph took place to the square, after all the faithful had previously bowed down; children were even made by their parents to pass under the Epitaph three times in length and width, so that they could be blessed. On the way back, they would distribute, as is the case today, the flowers of the Epitaph to the faithful. On Holy Saturday morning at the service, when the priest says “Arise, God, judge the earth,” he scatters bay leaves, which the women try to grab before they fall and hold them for the plucking.

Late in the evening of Holy Saturday Saturday is the Easter service, the house is clean, decorated, the sweets and Easter food smell sweet and inviting, everyone is well dressed, happy, ready to watch the resolution of the drama, the Resurrection, and to celebrate the victory of life over death. When the clock strikes twelve, they all sing together outside the church “Christ is Risen”, wish “Happy Birthday”, hug, kiss, crack their eggs and say “Forgive”, to show that all differences and quarrels are forgiven and forgotten and love prevails. The Easter service follows until about 2 a.m., which almost everyone attends. Returning home, we cross the lintel of the front door with the flame of the candle, to show that this house brings the blessing and joy of the Resurrection and we light our candle with the Holy Light. The festive table is ready and everyone is set to enjoy the traditional magiritsa, with entrekia, eggs, tsoureki and sweet wine. We do not set the table immediately, but the next morning.

Niki Kartali (right) and her friend Mastichenia Vathrakea crack their eggs one Easter.

On Easter day, the big feast takes place, the lambs are patiently roasted on a spit since dawn, or stuffed with rice or vegetables since evening in wood-fired ovens, the tables overflow with delicacies, traditional songs resonate and the wine flows abundantly ∙ the Greeks feast. Of course, they once didn’t eat much meat (probably due to economy), they preferred tsoureki, kouloures, red eggs, halva. At 12.00, the Second Resurrection takes place in the church. Throughout the rest of the week, the “asprovedomado”, the feasting does not stop, essentially, until Thomas Sunday, when it is Antipascha, the end of the feasting.

20/7 of Prophet Elias of Theovitos

(Custom of refugees from Agios Vlassis of Eastern Rumelia)

Prophet Elias, the Saint of the mountains, was celebrated in the village of Agios Vlassis of Eastern Rumelia with the sacrifice of a bull, a custom that dates back hundreds of years, but which was abandoned after their becoming refugees and settling in Nea Kessani. At the end of the summer, everyone, without exception, waited for the day of the feast of Agios Lios, to carry their bundles, neither earlier nor later. On this day, they made a kurbani (=animal sacrifice) in honor of the Saint being celebrated and for the health of the village, although the patron saint of the village was Saint Athanasius. We do not know exactly why, and the villagers who give us these testimonies simply say: “it’s been raining for years”. It was probably a remnant of an older ceremony, in which all the villages, which were built on the mountain of Ai Lias with the Saint’s monastery as their epicenter, participated. The entire celebration was considered a consecrated tradition, from which it was forbidden to deviate.

So on the 20th of July, all the men of the village gathered, led by the priest, at the threshing floor, which was a few meters away from the church, where a well-fed bull awaited them, tied to a large tree. This bull, bought with a donation from the villagers, had to be 2-5 years old, uncastrated (boulas), of any color except black and not to be tired, nor to have ever been yoked. Women were prohibited from the entire ritual. First, they stuck a candle to its horns, incense was burned on it and the priest read a prayer. Then they opened a pit, into which (the previous year) they had thrown the tail, ears, horns and bile of last year’s bull, so that “the dogs would not eat them the next day”, one of the villagers, after crossing the animal’s neck with his knife, cut its throat, taking care that all the blood spilled into the pit. With this blood they crossed the foreheads of the children for “gerosyn'”. This was followed by the grating and chopping, accompanied by bagpipes. Small pieces were distributed to the houses and the rest was boiled with rice for the evening feast at the threshing floor; everyone brought bread, salads and whatever else they wanted, while as they drank they poured a little wine on the ground as a kind of libation to the dead.

They did not leave the bones to the dogs, but threw them on the roof tiles. This entire ceremony, the “antet’”, was performed with religious devotion (despite its purely pagan character), in honor of the Prophet Elijah, and they believed that if they omitted anything, illness and disaster would fall upon the place.

An hour’s drive from the village was the monastery of Ai Lia, long since ruined. Tradition says that once upon a time, a deer would go there every year to be sacrificed (= sacrifice) for the Saint, but one year it arrived tired and the residents slaughtered it before it could rest, so it did not come back and from then on they began to slaughter a calf.

26/7 of Agia Paraskevi

Agia Paraskevi protects the eyes, the most precious asset of man. Just outside the village, towards the lake, a white chapel is built in the name of the Saint. It was built before World War II, because of a prophetic dream that an elderly gentleman had. Since then, it has burned down twice for unknown reasons, a fact to which some unpleasant situations have been attributed, such as the drought that occurred for a while. However, it was rebuilt repeatedly and today, thanks to the tireless work of the village priest, it is magnificent.

Every year the church celebrates and on the eve of July 26th a festive vespers is held, to which the whole village and many people from Xanthi and other villages flock. There is a bread offering with breads that some offer in the name of their own, they put the breads five by five in wide baskets, with a bowl of wheat in the middle, where they fix five candles in a circle and a small candle. The priest reads the breads and commemorates the members of the families who make the bread offering, holding in his hands a bread from each basket, then they cut them into large pieces and distribute them to the people, usually girls, in the baskets. This is followed by the prayer of the Saint and the established three-course feast in our square. The qurbani is distributed either on the eve after the prayer, or on the day after the liturgy.

06/08 Transfiguration of the Savior

On August 6, our church celebrates the Transfiguration of Christ on Mount Tabor, in front of his three disciples before he was crucified and at night, they say, the heavens open. On this day, the farmers of Nea Kessani bring the first grapes to the church, place them in front of the icon of the Savior, the priest blesses them, wishes them a “good harvest” and distributes them in the church, so that everyone can taste the sweet fruit.

15/08 Dormition of the Theotokos

On August 15, our Church celebrates the Dormition of the Theotokos and this is the greatest Theotokos feast of the year. Our people describe it as the “Easter of the summer” and it is as beloved as the holy face of our Virgin Mary. The feast is preceded by a fast that begins on the 1st of the month, as well as the celebration of the Prayer to the Virgin Mary every afternoon (except Saturday) until the 13th of the month. On this day, the faithful flock to the churches to honor the beloved holy person and a festive meal usually follows. especially in homes where there is someone or something celebrating (and there are many such homes).

29/8 Beheading of John the Baptist

On August 29th we commemorate the beheading of John the Baptist, which is why it is a great fast. In the past, they did not eat black food, such as olives, black grapes, eggplants, black wine, nor red, such as watermelon, tomatoes, etc., because they said that they were watered by the blood of the Saint. They still did not cut the head off any fruit, vegetable, or bread, in memory of the Saint’s beheading (we still observe this).

14/9 Elevation of the Holy Cross

The church of the village of Nea Kessani celebrates this day. From the evening of the eve, a festive vespers is held, the church is decorated with flags, and on the day the service is held, which everyone attends. Tradition says that when Saint Helen was searching for the Holy Cross of the Lord and wondered which one of them was it, she understood from a fragrant basil that grew next to it. Thus, on this day, many sprigs of basil are taken to church, which are shared after the liturgy. These sprigs are called “cross flowers” and are sacred; after the liturgy, the women prepare unleavened dough, put it in a bowl, add cross flowers, cover it and, oh my goodness, the dough rises without yeast. In the evening, a wonderful feast is held.

26/10 of Saint Demetrius the Great Martyr of Myrrh-Bearing

Saint Demetrius, patron saint of Thessaloniki and protector of farmers and herders, is honored throughout Greece with special reverence, and his feast is a milestone in the lives of winegrowers, who open the barrels and taste the new wines. Saint Demetrius also used to mark the end of the term of the shepherds who guarded the sheep, goats, and oxen, at which time they looked for new owners.

In our village, therefore, on the feast of Saint Demetrius, a custom was held, which is probably related to this event, rather than to the Saint himself. On the eve of the festival, a small group of young men, usually shepherds, would rouse the entire village. They would dress strangely in sheep’s skins, lots of clothes, wear large bells and hold a glitsa. One of them would necessarily dress as a woman – the jamala – whom the others were supposed to claim. So they would go around and enter houses and improvise short performances, always trying not to be discovered. The villagers would give them wheat or whatever else they had. On the day of Saint Demetrius, everyone would gather and feast with the money from the jamalas. This custom has been abandoned.

30/11 of Saint Andrew

The Thracians said that on Saint Andrew’s day the cold “strengthens” and is followed by the “Nikolovarvara” which marks the beginning of winter and harsh weather conditions. In our village, on the eve of Saint Andrew, the housewives of Northern Thrace would prepare a pie, usually a cheese pie, and distribute it to the neighborhood with the wish that it would “strengthen” the wheat they had sown in the fall. Some would make the so-called “assoure”, that is, boiled wheat, mashed, with cinnamon, herbs and nuts. Eastern Thrace housewives make assoure on the eve of Saint Barbara and call it “barbara”.

4/12 of Saint Barbara

On the feast of Saint Barbara, housewives make “barbara”. We boil wheat (kolyvozoumo) adding sugar, raisins, dried figs, some also add legumes such as chickpeas, and we serve it in bowls with roasted sesame, sugar, crushed walnuts, cinnamon and herbs and distribute it in the neighborhood “for good”. In the past, they believed that Saint Barbara protected children from smallpox and the sweet they distributed (traditionally to three houses) was their offering to the Saint, to protect children from the evil disease.