The story of the Kartalis family

During the 20th century, events occurred that left an indelible mark on both global and Greek history. Our homeland, through continuous struggles, military and political successes, as well as national tragedies, finalized its borders and emerged as a modern state.

The most defining of all events was, in 1922, the Asia Minor Catastrophe and the definitive refutation of the Great Idea. The Greeks of Asia Minor, Pontus and Eastern Thrace saw their lives turned upside down forever, as they had to abandon their ancestral homes and take the painful path of refugee. They had to go “through fire and iron” to survive the war and their violent displacement, and when they arrived in Greece, they had to build a new life from scratch, in a place that was both a homeland and a host country. Their heroic path from tragedy to creation and progress was admirable. Who can deny that these were the true protagonists of History? They themselves are no longer alive. However, their stories remain alive and travel from generation to generation through the narratives of their descendants. Because man is bound by his roots, is defined by his family past and wants to remember. Because the greatest of all is the legacy of memory.

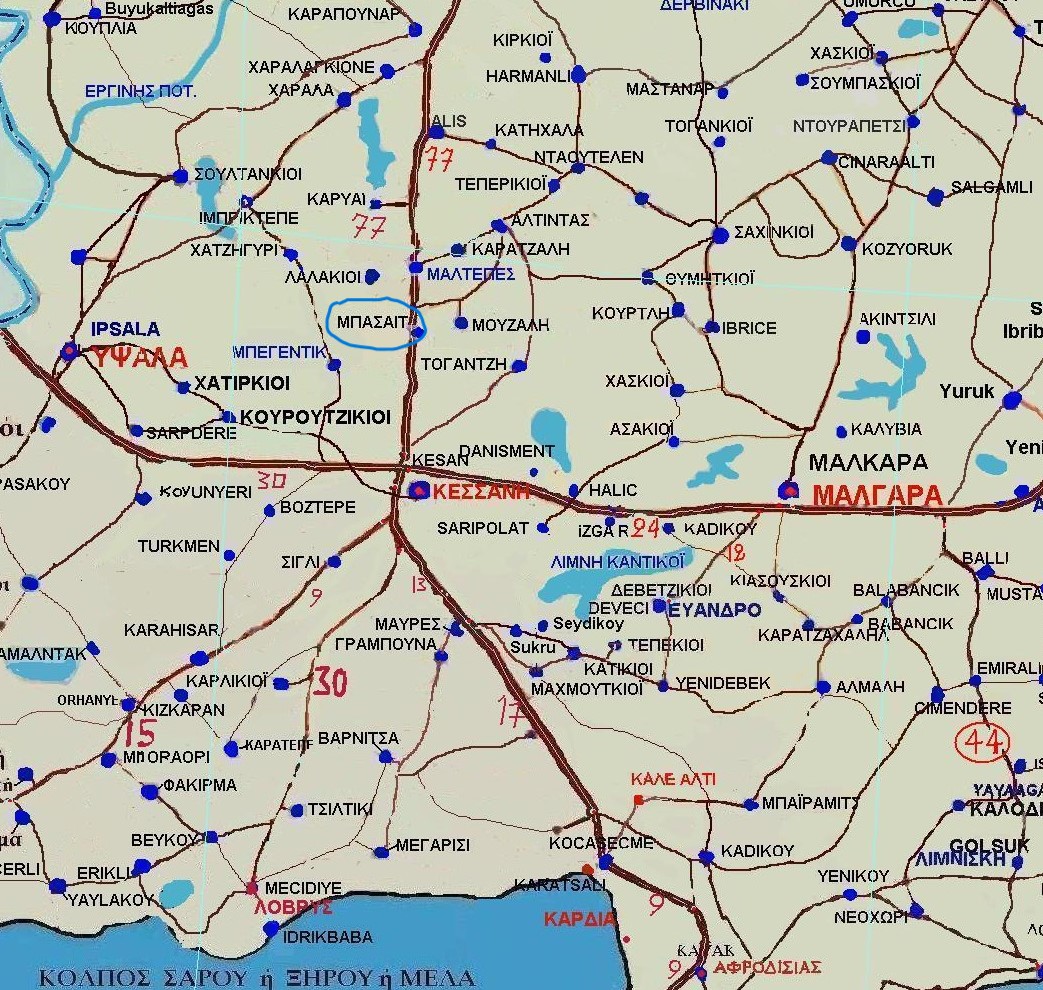

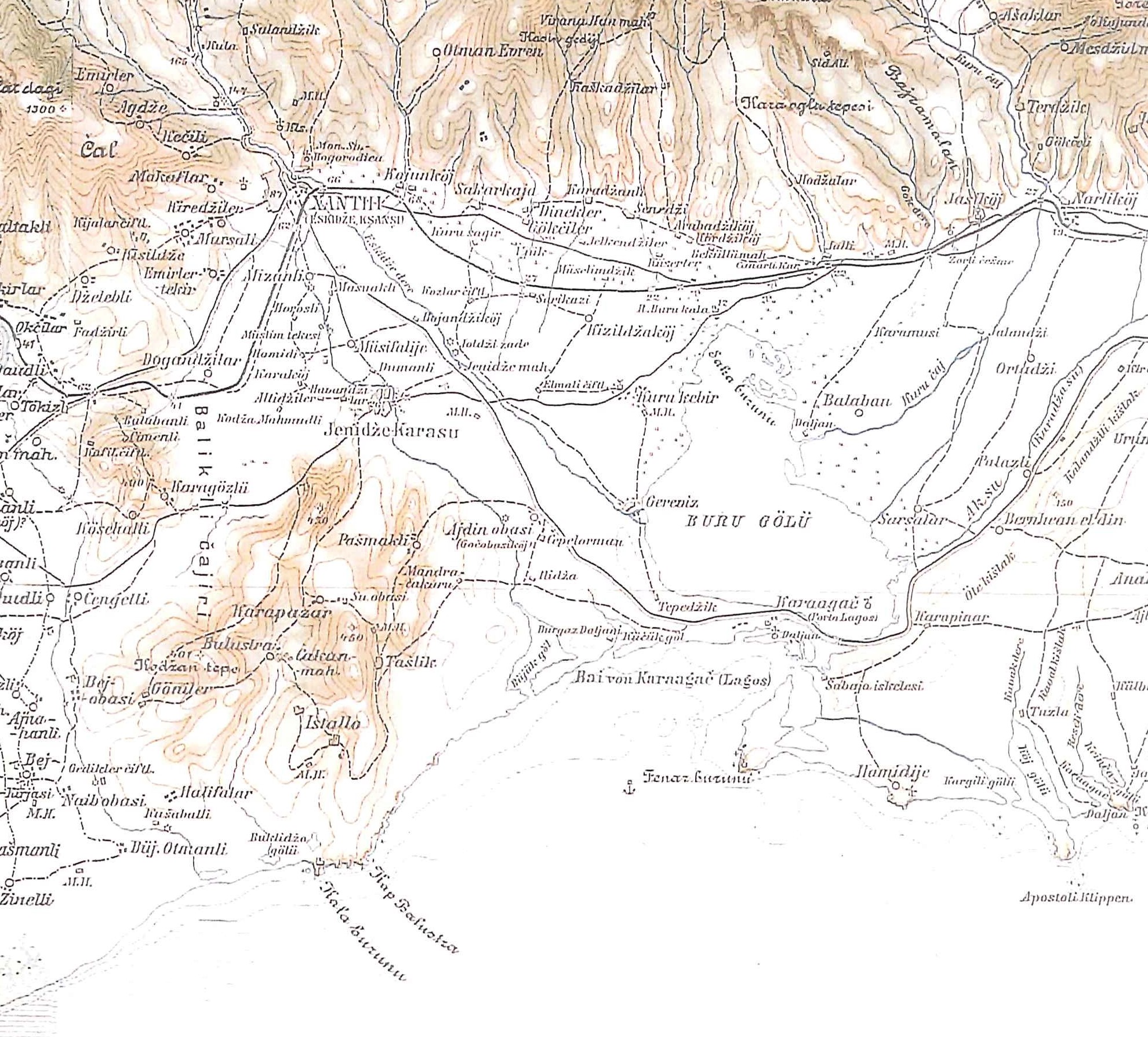

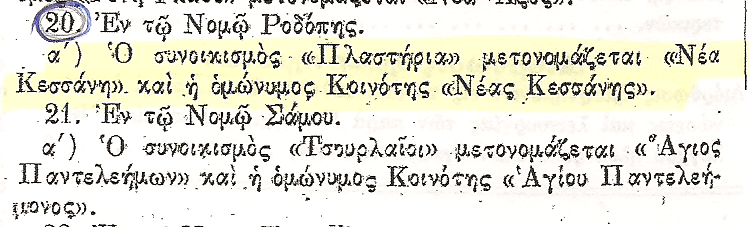

There is a village in the south of the prefecture of Xanthi, next to Lake Vistonida, which carries the rich legacy of the memories of the Thracian refugees who created it 100 years ago. Its first name, Plastiria, in honor of the general and benefactor of the refugees, Nikolaos Plastiras. The second, Nea Kessani, to remind one of the lost homelands. Its location is idyllic, next to the large lake and near the port of Porto Lagos. The first refugees who arrived in the place considered it suitable to settle after their long and hard wandering. One of them was Christos Kartalis, the father and leader of a great family of worthy Thracians, whose history is worth knowing.

Before 1922 and departure from Eastern Thrace

Christos was then a 20-year-old lad (born in 1902), Zisis a 16-year-old teenager (born in 1906), Anastasia a 13-year-old girl (born in 1909) and Sofia a 7-year-old child (born in 1915). Arriving at the Evros River, Christos, as a young and robust man, was drafted as a conscript to help the exhausted refugees cross the river. The exact route they followed is not exactly known. They made some stops in the prefectures of Evros and Rodopi, but in none of them did they decide to settle. At their last stop, in a village in Komotini, Christos, along with his father and fellow villager, Giorgos Albanidis, decided to search for a suitable place for permanent settlement on their own, and then bring the rest.

George Papazoglou, a distant relative of the family, vividly describes the uprooting:

“In October, the people of Hadjigyri had finished threshing, had carried the corn and had harvested. Their holds were full of crops. With a heavy heart, preparations for the “lift” began. All of them had the hope within them that something would happen and they would stay in their place. After all, for the last 10 years they had been accustomed to persecution. They could never understand this sudden change in their fortunes, the transition from the happy and glorious days of the two-year period 1920-1922 to the misery of refugee life. On Friday, October 6, 1922 (old calendar) in the afternoon, they went to the cemetery and said goodbye to their dead, who would leave them forever in their native land. They lit their lamps for the last time and said goodbye to them.

The Evros River is 20 kilometers away from their village. Thus, they reached the border and crossed into Greece on the same day, Saturday, October 7th. In October 1922, there was a lot of rain and the river was dangerously swollen. The people of Hadjigyri crossed over the bridge that existed in the village of Kalterkozi, today’s Poros.

Unlike most of the Eastern Thracians who moved to the south (Raidesto, Iraklia, Epivates, Peristasi, etc.) and from there crossed into Greece by boat or by train, without their flocks, the people of Hadjigyri, like all the Christians of the Kessani region, moved on foot, mainly by ox carts. And because the distance from the Evros River and free Greece was short, but also because only pedestrians could save part of their property and have some supplies to survive. Farmers and livestock breeders as they were, they would not have been able to move their herds otherwise. They took the large animals (oxen, cows, buffaloes, sheep and goats) with them and left pigs and poultry. They wrapped quilts or sheets and made bogos, “bochtsiadis”, for the transport of clothing, textiles, etc. They hid some objects in the holds or even in the wells, to find them when they returned, as they believed. As soon as evening fell, they boiled water in cauldrons and put the pies, the honeycombs with the bees in the hot water and took the honey. They slaughtered a few chickens and prepared food for the journey. They also took with them the icon of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, from 1850, from the church of the Virgin Mary. It was transported by the refugees from Hatzi-gyriotes and in her honor the church of Pigadia was named after her.

The carts were not enough to cover their needs. Therefore, because the distance to the river was short, about twenty kilometers, the most “tsorbatzids” made two or even three trips, some paid local Turks to transport them with their own carts, while others called their relatives from the neighboring villages of Maltepe, Basaiti, Beyndiki, Kordjiki and for safety reasons they moved in families. The movement took place together with their flocks.

The movement was relatively safe, unlike the movement of other eastern Thracians, who moved from areas further east than Kessani, from Rai-desto, Tyrol, and Tsataltza. They were attacked by Turks who were biding their time to rob them or take part of their herds.”

Arrival at Tepe – Tsiflik, creation of the settlement of Plastiria (late 1922 – early 1923)

Thus, when they found themselves in Tepe Tsiflik, as the area was called, which previously belonged to a Turk, Hadjis Ali Bey, they considered that it was as they wanted. Obviously the lake, which would provide them with clean water and fish, the sea which is not far away, but also the urban center of Xanthi at about 20 kilometers, were enough reasons to make the decision.

= = Thus, they slowly began to settle down and hope for a new beginning. However, some of the relatives and fellow villagers of the Kartalis family continued their journey and arrived in Iraklia, Serres.

Initially, they settled tentatively in tents provided by the army. According to the tradition of our village, Nikolaos Plastiras himself passed through the place, saw the desperate situation of the refugees and personally took care of their rehabilitation. What is certain is that the revolutionary government headed by the great general proceeded with decision no. 3473 of February 14, 1923 to the “mass expropriation of farms, manors and communal lands”. Thus, Tepe Tsiflik became a refugee settlement and was named Plastiria.

Then the state provided the refugees with the necessary timber and they made mud bricks to build the first houses in the north of the village (higher than the modern square). They all worked together, tirelessly and persistently, in solidarity; after finishing one’s house, they would start another. From then on, the young Christos Kartalis showed his dynamism and his willingness to work for the good of the community. So the worthy Thracians, building the houses in their new homeland, shared the work, the materials, the suffering and… a wall, because their houses were duplexes. On the border of two plots of land, two houses joined by a common wall and the sloping roof, which naturally belonged to different families. The common wall had a small window, through which the residents communicated and exchanged anything they needed. Christos’ family built their duplex with his father’s cousin, Adam Kartalis, to the east of the settlement near the lake. Adam Kartalis was married to Maria and had two children, Dimitris and Panagiota. According to the Thessaloniki newspaper “Fos” (Light) on 29/09/1923, 75 houses had already been built in the settlement of Plastiria.

1923 – 1939, family formation, arrival in Plastiria of Northern Thrace, progress

Housing was the first main goal. At the same time, however, they had to secure their livelihood. Christos’ family had brought their large animals and this was a significant advantage. They also began to work the small pieces of land that had been granted to them. The titles for these fields came into their hands, of course, in 1931 when Plastiria became a separate community along with Potamia and Porto – Lagos, with our village as its headquarters (from 1924 to 1931 the settlement belonged to the community of Genissea). Then the official distribution of land to the landless refugees was carried out by the Settlement Offices, which had been organized by the Refugee Rehabilitation Committee (the headquarters of the General Directorate of Settlement of Thrace was Komotini). The agricultural plots were from 30 – 40 – 50 acres, depending on the number of members of each family. The men of the Kartalis family worked tirelessly on the land, not only to secure the necessities, but also to increase their plots, which they gradually achieved. The following description by N.K. Laios, a settlement official in 1927, fits them perfectly: “The Thracian peasant, shepherd or farmer, is a calm and reasonable man, slow and serious with simple and normal habits. He gives the impression of a measured and stable person, which is typical of people devoted to the land. He judges things calmly and coolly, thinks a lot, is hardworking and tolerant but also stubborn, … in a conservative way...”

The conditions were certainly not easy. There was no financial assistance, not even the possibility of a loan in the early years (the Agricultural Bank was only founded in 1929) and of course the technical means were poor. The village roads were dirt and, when it rained, the mud made movement very difficult. Access to drinking water was also difficult. As Giannakos Kartalis remembers, there was a well for the animals outside the village, but a well in the plain had good water. The villagers would go there by cart once a week, fill one or two barrels and use them to meet their needs. He also remembers that some people would get water from a well in the neighboring village, Selino, but that water was not that good. Another big problem, also related to water, was malaria, which plagued the villagers for many years and the state’s efforts to deal with it were not particularly successful. As for medical care, it was almost non-existent. There was a doctor in Yenisea, but even traveling there was difficult. The only medicine that was easily found was quinine, while folk medicine (the giatrosofia) usually solved the problem.

Despite the difficulties, Christos Kartalis’ family not only made it through, but also made steady progress. In August 1927, 25-year-old Christos married 20-year-old Giannoula Noikokyridou, daughter of Christos Noikokyridis, who came from Begentikioi in eastern Thrace and was a charming and dynamic girl.

Their first child, who is recorded in the community’s municipal records, was born on November 15, 1928 and was named Keratsouda, but she only lived for five days and passed away on November 20. The next child was Ioannis, whom everyone still calls Giannakos, for his gentle and sweet character. Giannakos is recorded to be born towards the end of 1930, but he believes that his real date of birth is 1929. The explanation he gives is that at that time parents declared a slightly later date of birth for boys, in order to somewhat delay their military service, since it lasted a long time at that time and the long absence of the boys in the family made agricultural work very difficult.

As the family grew, so did their livelihood, as the dynamic Christos, together with his father and brother, worked hard to be able to buy more fields and become a successful and important family in the village. Christos even seemed to be developing into the head of the family and taking care of everyone and everything. For example, during a walk with friends in the village of Gkiona (perhaps to find new fields or simply for fun), he met the beautiful Zoumboulia Ampartzakis, also a refugee from Eastern Thrace, and he considered her a suitable bride for his brother, Zisi. He wasted no time, met them and indeed the couple got married in November 1935.

In the meantime, Plastiria had changed its population composition and had grown considerably. Because on Christmas 1928, 40 families arrived from Northern Thrace, Eastern Rumelia, which belonged to Bulgaria and the robust Greek population was being expelled from there. The new residents came from the village of Agios Vlasis in Mesimvria, from where they had left in 1924.

When they arrived, Plastiria already had 336 residents (May 1928 census), who were disturbed by the arrival of the new refugees. They settled in the southern part of the village below the modern square and with basic financial assistance from the state they built their houses and started their lives, bringing new life to the village. Three years later they also received a plot of land. The relations between the two parties were explosive from the beginning, as the Eastern Thracians and the Northern Thracians for several years focused on the differences they had, mainly in terms of their morals and “customs”, but the common problems on the one hand, the strength of habit due to coexistence on the other, led to the normalization of relations and the first marriages between them. For example, Christos Kartalis’ sister, Anastasia, married in November 1936 Nikolaos Alexiadis, a native of Northern Thrace, who had the most sophisticated café-grocery store in the village, while their first son, Vasilis, studied civil engineering and later supervised the construction of most of the village’s newer houses.

Thus, the 1930s were nothing short of a period of rapid growth for our village. Some additional factors that helped were that agricultural products were sold at better prices, many farmers’ debts were written off, and in 1937 the construction of the road between Xanthi and Porto Lagos began. Indicative of the economic importance that Plastiria quickly acquired is the fact that until about 1940 the extremely active villagers were additionally taxed for the products they transported and sold in the city of Xanthi. The tax collectors had their haunt outside the village cemetery and meticulously checked the carts that went to Xanthi for products to be taxed. There were of course difficulties, such as the great problem of malaria and the inadequate state infrastructure, but the first generation of refugees had lived through worse and knew how to work hard and progress. Before 1940, according to testimonies, Christos Kartalis was elected president of the village for a term, a fact which on the one hand demonstrated his interest in the good of the place, on the other hand gave him the opportunity to help his fellow villagers more effectively. At the same time, he built his own house near the village church, the location of which he had suggested. His parents, Zisi’s family and Sofia now lived in his ancestral home.

1940s: Renaming of the village, World War II,

Bulgarian occupation (April 1941 – September 1944), civil war (1945 – 1949)

However, the positive course of the community was interrupted by the entry of our country into World War II with the Italian attack through the Greek-Albanian borders. A few weeks before, on September 3, 1940, the Official Gazette was published with the decree renaming the village from “Plastiria” to “Nea Kessani” (fact that was realized about ten years later)

As it is known, after the Epical Greco-Italian War, the German attack followed and in April 1941 the occupation of our country and the beginning of the triple occupation. In May 1941, the German occupiers handed over Xanthi to their Bulgarian allies, who once again tried to de-Hellenize and Bulgarize Thrace.

Their first move was to requisite all the good houses, in order to settle Bulgarian officers, soldiers, and civilians there. In our village, one of the requisitioned houses was that of the family of Christos Kartalis, as well as the school building, which had been built in 1931. According to the testimony of Giannakos Kartalis, who was 11-12 years old at the time, there were many Bulgarian soldiers in the village. 7 Bulgarian soldiers and a sergeant stayed in their house, who succeeded the German soldiers who had preceded them. The characteristic of the time was of course hunger, since the Bulgarian army had requisitioned all food and with great difficulty some villagers had managed to hide a few grains, which they ground with a hand mill, in order to eat a little and not die of hunger. Because the situation was even more difficult in the city of Xanthi, people from Xanthi often came on foot to the village, to sell something, even their dowries, to get a few eggs, or simply to collect turtles, which, as they said, tasted like chicken. Giannakos Kartalis remembers that his mother, Giannoula, once bought a rag from a woman in order to help her economically, because she was ill.

On the other hand, since life moves forward even in adversity, thanks to the power of love and hope, Sophia, Christos’ sister, married Kostas Alexandridis, a resident of the village (originally from Karatza Halil in Eastern Thrace), in June 1941, and their first child, Apostolos, was born in October of the following year. The ability of this family to flourish even in the most difficult circumstances is admirable!

During the occupation, the Bulgarian occupiers allowed the villagers to speak Greek (something that was forbidden in Xanthi), but they were very strict, violent and often imposed heavy chores on them, such as traveling to Xanthi on foot to transport animals for slaughter. Also, in the area of Bairá, they had built detention centers, as well as fortresses for their anti-aircraft defense and transported two barrels of water there daily for the soldiers’ needs. Their characteristic, however, was poverty. As Giannakos Kartalis recalls, the German soldiers who passed through the village were better dressed and equipped than the Bulgarians, who appeared ragged and hungry.

Another aspect of the era were the “dourdouvakia”. The word means a soldier, not a combatant, but a worker in forced labor battalions. Bulgaria needed cheap labor for some public works, such as opening roads; the easiest way was to forcibly conscript the occupied Greeks of Thrace, which they did. Thus, in April 1942, the young men of the classes of ‘41 and ‘42 were called up. On May 1, 1942, about one hundred and fifty young men from the prefecture of Xanthi were at the railway station with a handful of clothes, forced to be crammed into small freight cars, to travel to the Bulgarian countryside, to various construction sites. There they lived in makeshift shacks under harsh conditions. They worked for 10 hours, with poor food, and if they had not been young and strong, they would not have been able to endure. Lice, fatigue, beatings, the poor condition of their bare feet tormented them. Some were injured by landslides of rocks and dirt.

Hostages (Dourtouvakia) from Mandra and Abdera in 1942 somewhere in Bulgaria

The late Thomas Exarchou, in his book “Hostages of Bulgaria”, mentions that one of our fellow villagers (he does not mention his name) was killed in a rock-blasting operation. From the list of hostages recorded in the same book we find the following names of residents of the village:

- Alexiadis Dimitrios

- Albanidis Dimitrios

- Vathrakeas Christos

- Vathrakeas Christodoulos

- Gialamidis Konstantinos

- Karakatsanis Dimitrios

- Karakatsanis Kyriakos

- Karakatsanis Georgios

- Kartalis Konstantinos

- Menexidis Konstantinos (from Potamia)

- Baraklianos Panagiotis

- Myrtzakis Angelos

- George Stavrakaras

- Konstantinos Stavrakaras

Fortunately, there were no tragic events with executions by the Bulgarian occupiers in our village, as happened in other places. And when the civil war began after the liberation, the peaceful people of Plastiria neither participated in any way, nor did they face serious problems. Twice, guerrillas passed through the village ∙ both times their main demand was food and supplies. The first time they also attempted to recruit villagers, mainly workers in the salt pans. Giannakos Kartalis recounts that the second time, as he was walking with two of his friends, they were stopped by two guerrillas with weapons in their hands and asked to talk. So they began to explain their ideas to them, but Giannakos was worried that he might be targeted, because of the wealth that the family had managed to acquire (they had already bought several fields in Fanari, Rodopi prefecture). Fortunately, the conversation did not last long, the guerrillas asked for water from a house, took what supplies they could (with 4-5 carts) and left.

1950s

With the end of the 1940s, the painful period of military conflicts and bloodshed for our country ended. Peace came along with the hope of regrouping forces and development. Christos Kartalis, always dynamic and active, was once again taking care of the village and its residents, as a member of the community council in 1950 (according to community documents), while he was also a cantor in the village church, which is dedicated to the Rise of the Holy Cross.

At a celebration in the village square on April 13, 1956, with grandfather Christos Kartalis in the middle of the congregation, performing cantor duties.

At the same time, the second generation of refugees was growing up, getting fat and enriching the place with youth and vitality. In 1950, Giannakos was twenty years old and Dimitros was eighteen. Working in the fields and with animals did not scare them. The family already had several acres, on which they cultivated wheat, rye, millet, and they also had vineyards. They had sheep, cows, oxen, and horses, which they took care of themselves, but they also hired shepherds who (as was customary) lived in the pens. In the fields, in addition to Christos and his two sons, other members of the extended family worked, so everyone earned money. They started at dawn and stopped at dusk. As Giannakos Kartalis remembers, after hard work, the young people had the courage to go for a walk in the village, with a portable gramophone-suitcase, like the one Paschalis Dafos had, to go to friends’ houses, especially those where there were not engaged girls, and to dance to the beautiful songs of the post-war era. Always modestly, respectfully and under the watchful eyes of their parents, of course.

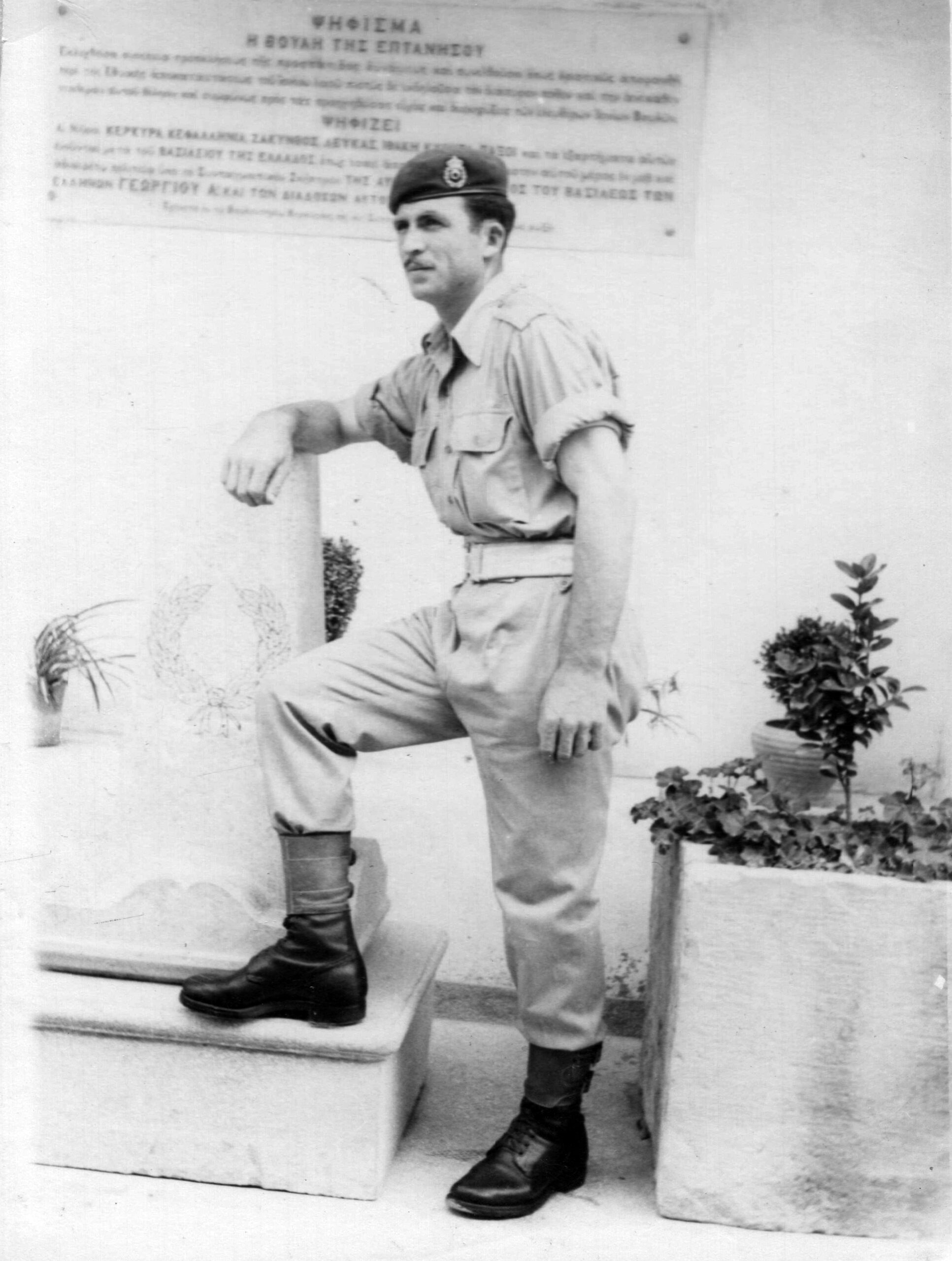

But the young men also had obligations to their homeland. In 1952, Giannakos began his military service, which lasted two years, in the artillery corps, with the specialty of cook. His brother, Dimitros, followed in 1954, also for two years in Igoumenitsa and Corfu. 1954 was also the year of local elections and the boys’ father, Christos Kartalis, was elected president of the village.

Giannakos Kartalis

Dimitros Kartalis

1960s

After fulfilling this duty, the two brothers returned to their father’s home and to their agricultural work, as always tireless and dynamic. In the meantime, Plastiria (which had changed its name, but people still knew it by its first name) had become particularly popular for its parties. Sometimes improvised, after the day’s toil, with the women’s songs and the accompaniment of an accordion or a harmonica (Yiannakos also had a harmonica), sometimes more organized, on Sundays in the square, three-story parties were set up and people from many villages flocked to it. That was when “love began to blossom”. As young people were caught in the syrto, the young man who was interested in a girl would go next to her and take her “by the hand, oh by the handful” and she, if she wanted, would squeeze her finger a little, to show her own interest. And while the young people danced and flirted so discreetly, their parents were proud, but at the same time they were watching the prospective grooms and brides, so that they could then arrange the matchmaking, in consultation with their children of course.

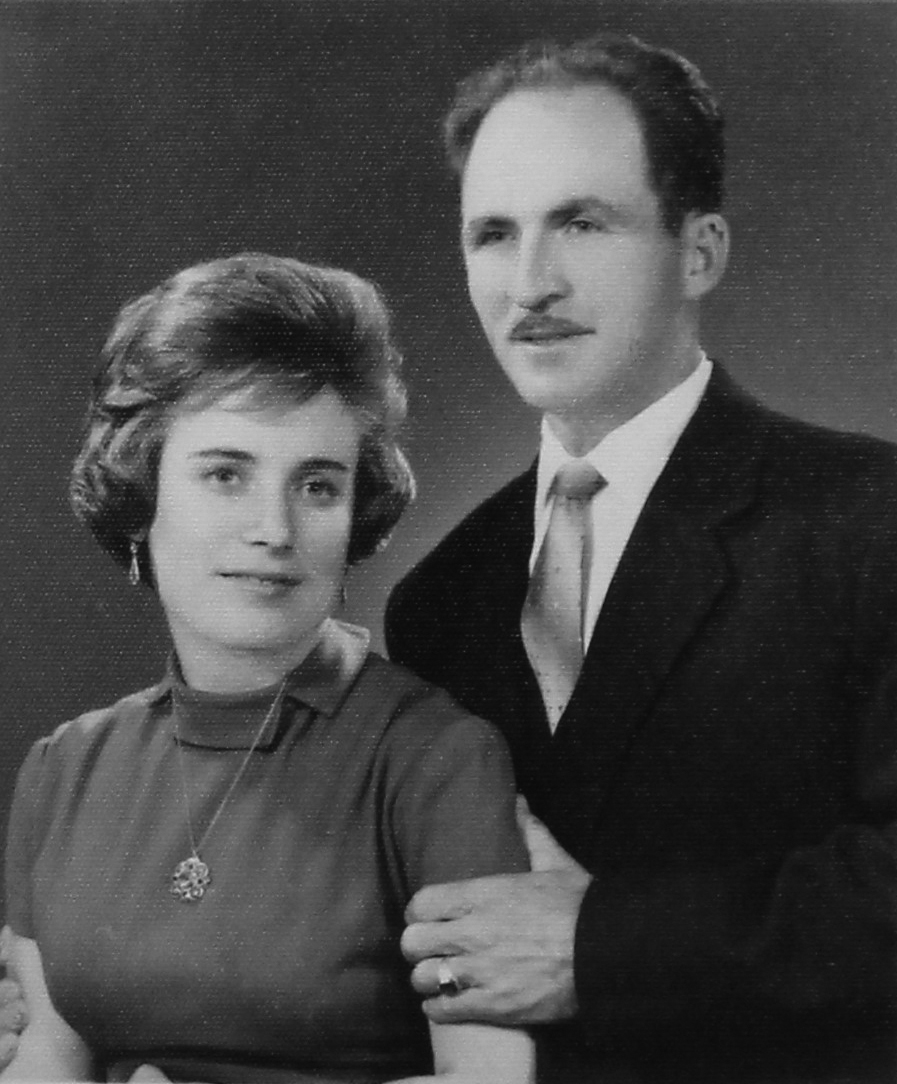

So the moment came when Giannakos Kartalis also took the wish of his father, Christos, and sent a matchmaker, to ask for the beautiful Niki, daughter of Evlampios and Anna Papantoniou, also refugees from Basait. The matched couple was united forever in the sacred bonds of marriage on October 21, 1956 and created a beautiful family, having three children, Christos (1957), Kostas (1958) and Gianna (1961), who made them very proud in the following years with their value, morals and successes.

After a few years, it was Dimitros’ turn to love and marry another beauty, Fotoula, daughter of Athanasios and Anthoula Stavrakara, also from Basait, Kessani. Their wedding took place on April 30, 1961, and the beloved couple had two worthy sons, Christos (1962) and Sakis (1966), both now eminent in their fields.

Ο Γιαννάκος με τη Νίκη

Ο Δημητρός με τη Φωτούλα

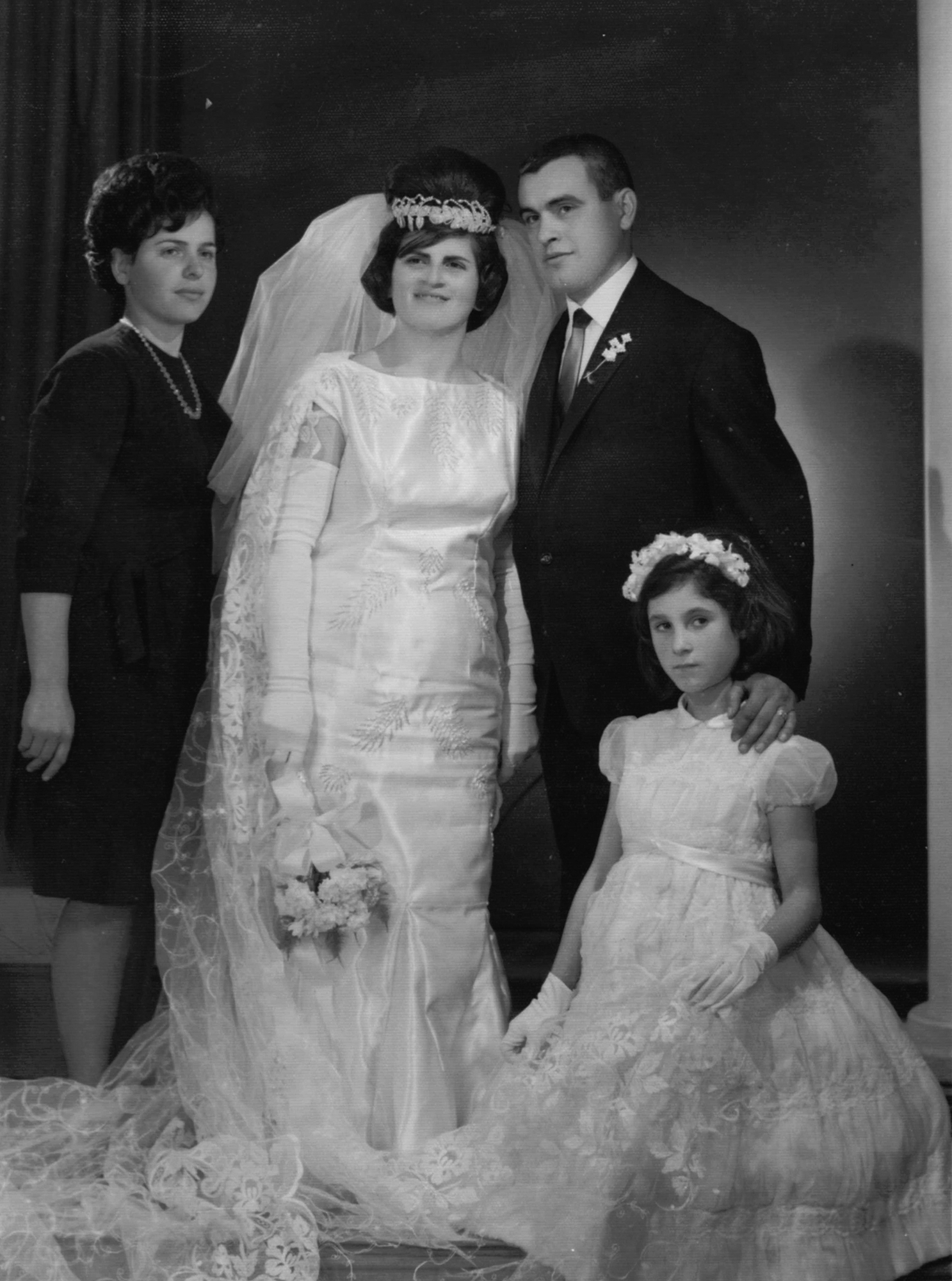

In 1963, there were two changes in the house. First, Giannakos and Niki built their own house near the village square, on a plot of land, inherited from his mother from a relative of hers, whom she had taken care of in the last years of his life. The plot of land was one of those given to the first refugees in 1923 and was large enough to accommodate a spacious house and all the necessary buildings for the couple’s agricultural and livestock operations. The other event was Virginia’s marriage to Xanthi native Nikolaos Akhtaris and her move to the city of Xanthi, where she created a beautiful family, having had her two children, Chrysa (1965) and Kostas (1972), of whom she can justifiably be proud.

Virginia Kartali, bride.

Virginia Kartali, bride,

between her brothers Giannakos and Dimitros.

up 1970s and 1980s (Colonel Dictatorship 1967 – 1974)

Christos and Giannoula watched their family grow and their home fill with joy, as they welcomed their grandchildren, one after the other. Protective and giving, they expressed their love by taking care of their every need, but also admonishing them sometimes severely, in order to transmit their principles to them, as well as to prepare them for the harsh terrain of life. That is why, for example, when they were old enough, grandfather Christos would take them with him to the fields, so that they could help him and see what agricultural work meant. In fact, he was particularly happy about Sakis, the second son of Dimitros, who loved the land very much and happily followed his grandfather to the farms, helping him with zeal. On the other hand, sometimes grandfather Christos would put his grandchildren on the platform and take them for a swim in Porto Lagos. On one of these occasions, the children did not want to get out of the sea, nor to return to the village. Grandpa called them once, called them twice, there was no third time. He got on the tractor and took the road back home alone. The children, to their great disappointment, understood firstly that they had to return to the village on foot and secondly that grandfather was not joking!

This is how Christos Kartalis’ family went through life, close-knit, united, with dignity and honesty, with a willingness to offer to others and, of course, with a lot of work and strict organization. As Giannakos’ daughter, Gianna Kartali, recently commented very aptly: “In this family, the word ‘tired’ was never heard.” Because their priority was success, not rest or fun. And everyone knew their place and their duties and everyone took into account the word of their father, Christos, first and foremost. In fact, they often worked not only on their own farms, but also, because their family was one of the few who had a harvester, they helped several of their fellow villagers with the harvest.

The next milestone in the modern history of our country was the imposition of the dictatorship of the Colonels on April 21, 1967. Apart from the upheaval caused by this shocking event, it had no other serious consequences for the lives of the village’s residents. In Athens and other urban centers, the persecution, fear and painful problems caused by an authoritarian regime made life particularly difficult for many (dissidents and not). However, in the countryside, the cancellation of farmers’ debts, public works, the economic progress experienced by farmers, but also the absence of anti-establishment action, made this period not particularly unpleasant for the residents of Greek villages, as well as ours. A characteristic event that Takis the Tall remembers from his grandfather, Christos, and which highlights the clear distancing from the politics that he had chosen, is the following: in 1974, when the Turkish invasion of Cyprus took place and conscription was declared in Greece, the seventeen-year-old Takis was following the events and was worried. However, when he caught up with his grandfather, Christos, outside on the street and told him, upset, what had happened, he calmly interrupted him, emphasized that all these events should not concern him, since he would not be conscripted due to his age, and took him to the field to pick up clover. Christos Kartalis was a practical and realistic man; he did not deal with political events, which he could not influence as a citizen. However, he was actively involved in the issues of the community in which he lived and in which his words and work had an effect. That is why he was once again a community councilor between the years 1968 – 1972, when Konstantinos Dafos was the village president.

The following years, after the transition to democracy, were calm and creative for the Kartalis family.

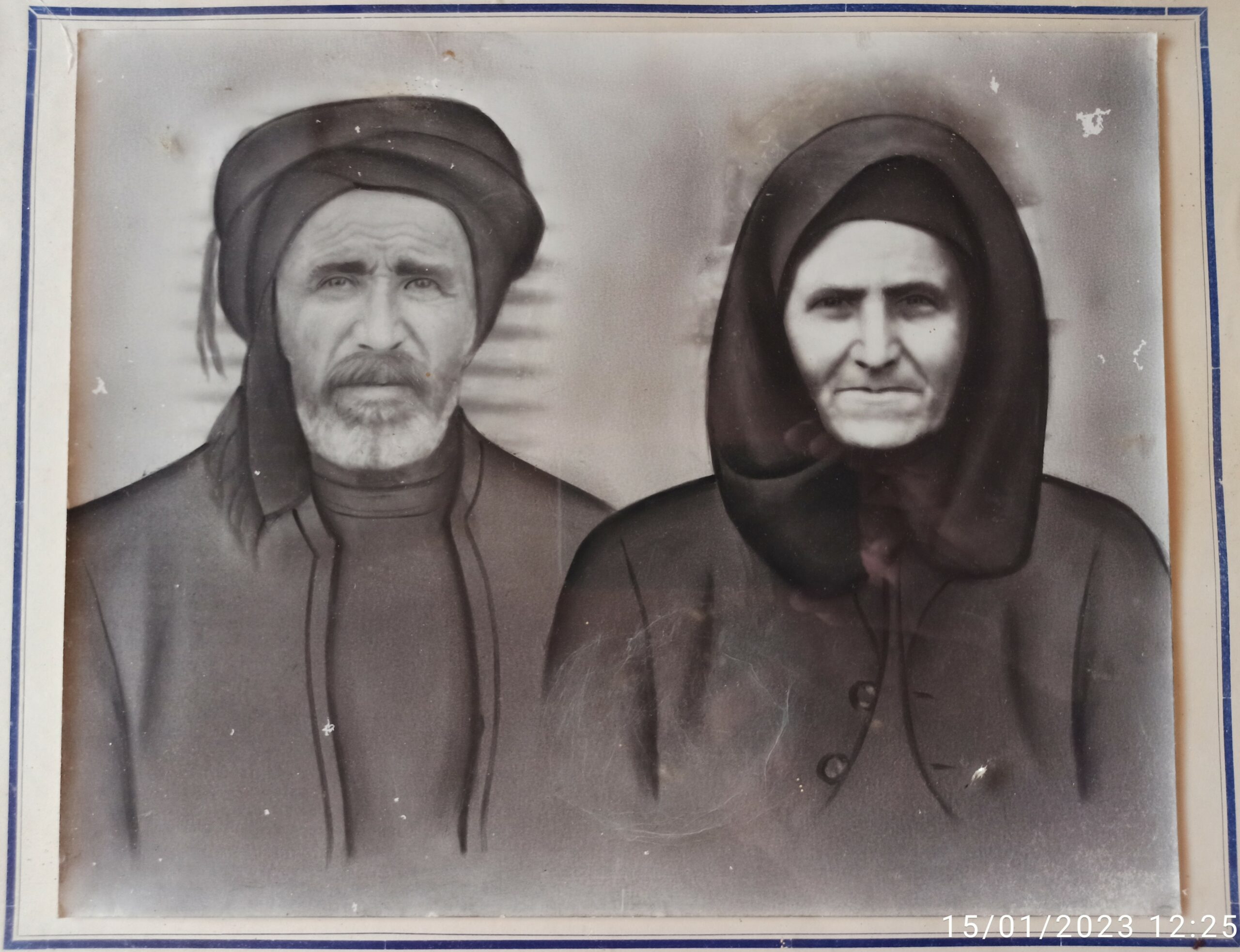

Christos and Giannoula took pride in seeing their grandchildren continue the family tradition of hard work and success, as they were educated and began their own journey with hope. But life sometimes comes full circle and for Christos this moment came in 1985. The entire village attended his funeral to bid farewell to one of its founders, a leading figure who dominated the lives not only of his own, but also of the entire community. It was a moving moment when the coffin with his body arrived at the house. The woman of his life, Giannoula (Noikokyridou) Kartali, came out alone to the door to greet him, Doric, serious, proud. The large crowd that had gathered fell silent, not even a whisper was heard, and as the coffin approached the entrance of the house, her voice broke the silence: “My master, welcome to your home”! Eight years later, in 1993, she also followed the path of eternity and passed into the history of her family, but also of the entire Thrace, as its worthy child.

Christos and Giannoula Kartali experienced the tragedy of the uprooting of Hellenism from its ancestral homes and the suffering of refugee life, but they endured, struggled and ultimately created an admirable family. Their legacy remains alive in their worthy descendants.

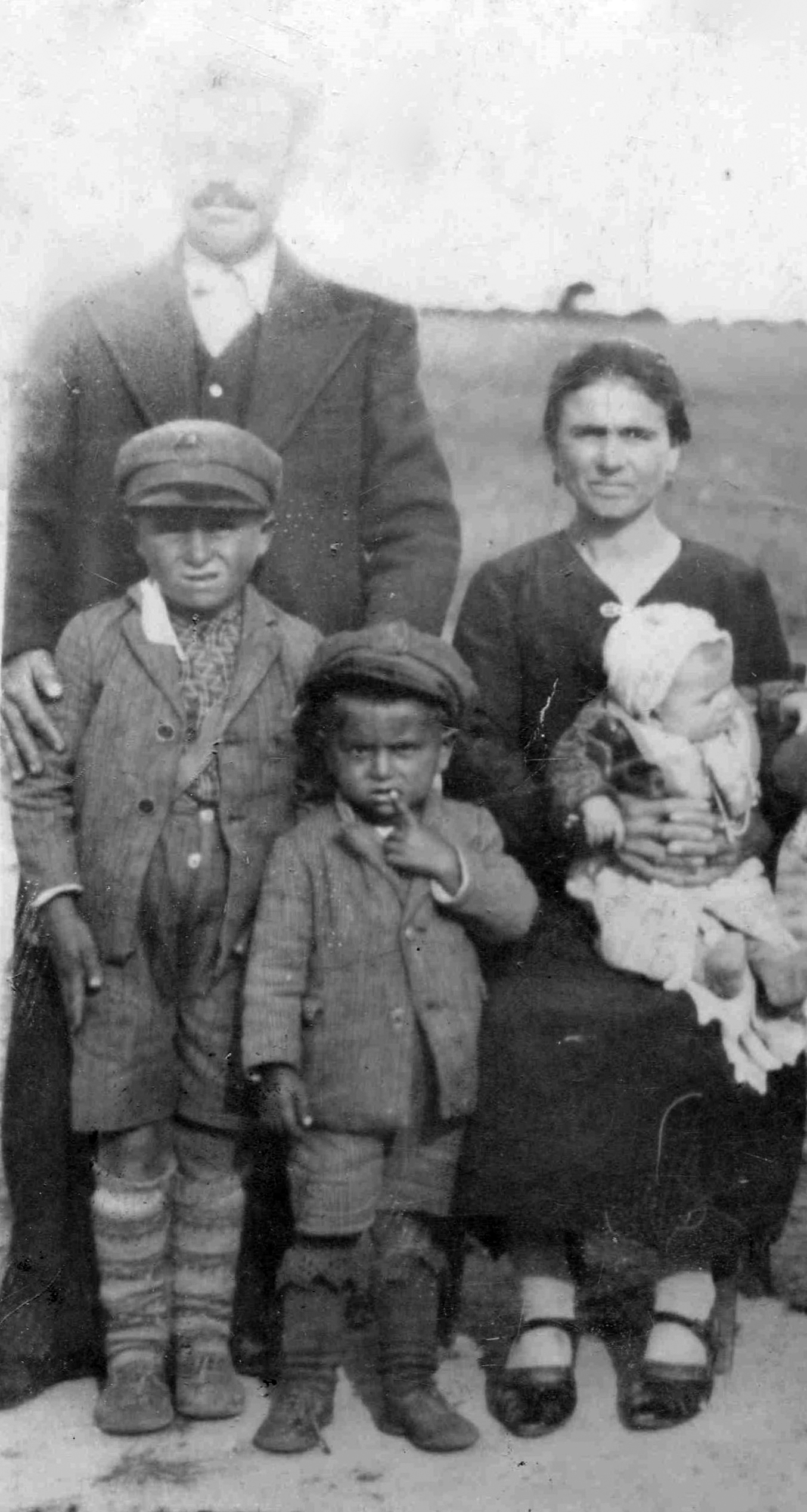

In the family’s first home: 1950 (from left) Giannakos Kartalis, his father Christos, his mother Giannoula, his brother Dimitros, his sister Virginia and cousins Dimitroula and Konstantinia Kartalis.