Socail life

History of Nea Kessani

The engagement took place one or two weeks or more after the wedding, on Monday evening for the Eastern Thracians and on Saturday evening for the Eastern Romylians. It never took place during Great Lent (Christmas and Easter) or in leap years. It took place at the bride’s house, where rings were exchanged in front of the icon of the Virgin Mary, gifts were exchanged and a feast followed. In the old days, in the homeland, a common gift from the groom to the bride was the silver belt, a metal belt, silver for the rich, bronze for the poor (bakirozounaro), which the young wives wore around their waists. The bride kissed the hand of her father-in-law, who gave her money and jewelry. In the Eastern Romulan engagement, the groom prepared a ring, a handkerchief and a doubla into which he threw other things, stragalia, raisins, and candies, and the bridesmaids, his parents, but not he himself, took them to the bride. The bride in turn prepared a ring, a shirt, and handmade socks and distributed them. At the end of the engagement, they fired rifles. Now the couple could move freely holding hands, not hugging, so that the world could see them and admire them. The engagement lasted 1-2 years or even longer, depending on the circumstances. During its duration, the couple exchanged gifts.Of course, innocent flirting didn’t just happen at dances, but on any occasion where young men and women gathered, even at work. They also found imaginative ways to see each other; for example, when some girls gathered in a house to spend their night cleaning several kilos of corn, the boys who wanted to see them would sneak into the yard where they were sitting, because this work was done in spring or summer, hide in the pile of cleaned corn leaves and talk to each other safely there.

So, somehow, “love begins.” Then, the boy consulted with his parents and, if they agreed, they sent the matchmakers. So, they, not the groom’s parents, nor the groom himself, went to the bride’s house with gifts and asked her parents for her, saying:

“We didn’t come here to eat and drink.

We only came to love you and to see you.

“Give us your girl to marry.”

or “We loved your daughter, we came to take her.”

If they didn’t agree right away, they tried a second and third time. Sometimes two matchmakers would go for two different grooms and the best one would win. When they finally shook hands, they would fire rifles so that everyone would know. On the night of the engagement, the dowry that the bride’s father would give to the groom was also arranged (a field, an ox, 20 sheep, etc.). When leaving, the matchmakers would leave as tokens of the engagement, a gold doubla (large coin) or a fluri (small gold coin) or a medjit (half a lira) that was sewn into the bride’s turban.

If the matchmakers failed, but the young man really wanted to take the girl, just as if the groom’s parents wanted to marry him to someone, but he loved someone else, he would steal her and take her to his house. So he would steal her and they would go to the priest, who would ask the girl if she was with him of her own free will and if she had slept with him; if so, they were free to marry, if not, she could leave (from the story of grandmother Despina Fylachtaki from Katikioi in Eastern Thrace).

Wedding / Joy

It is no wonder that wedding customs are among the most beloved subjects of folklorists. Marriage and the creation of a family were and are the most important events in a person’s life. It is therefore natural that the wedding ritual, as well as everything related to it, is rich in customs and beliefs.

Courtship and flirting

The matchmaking was arranged by the parents and the boy’s family always sought the girl. The parents judged and chose the girls and boys, among other things, on the basis of the dance. The feasts were quite extensive and three-layered. They ate, drank and, above all, danced. The East Romulans would catch women and men in turns, while the East Thracians would catch all the men first and then the women (the first woman with the last man in line would be caught with a handkerchief); the adults would form a circle like a wall around the dancers and brag about their children. At the same time, they would watch who was wearing beautiful clothes, who was elegant, their posture, who danced best, who was more lively, who was dancing with whom, etc. Love would also begin during the dance. When a young man was interested in a girl (at dances where they took turns, of course), he would go to catch her at the dance; if she liked him, she would catch him, but if he had any flaws, she would not separate from her girlfriend and would not let him dance with her. So they would catch each other, only by the little finger (not by the fist), and the young man would squeeze her finger, at first she would not respond, but the second time she would squeeze him too and that was how love began and was declared.

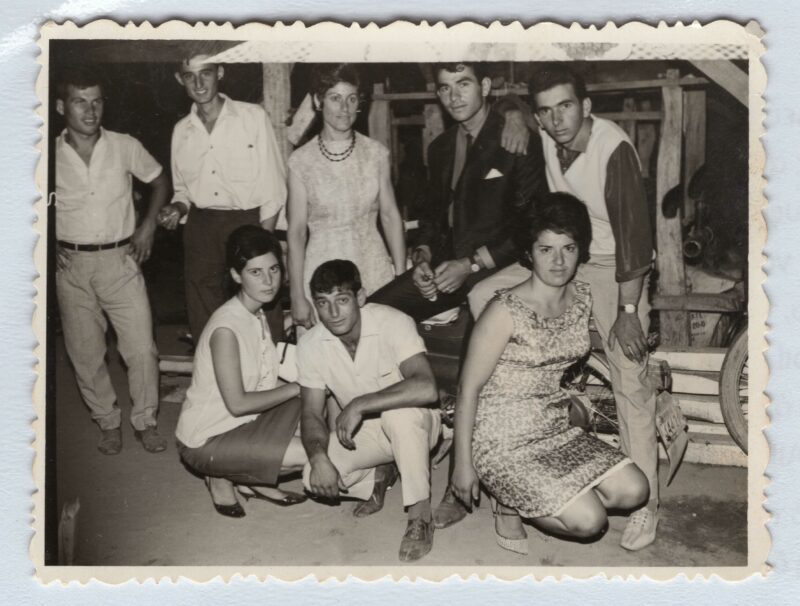

Below left, seated, Eleonora (Lola) Stavrakara, on the right, seated, Athanasia Drakou, behind her, crouched, Sotiris Baraklianos, and next to him, Vangelis Drakos.

Of course, innocent flirting didn’t just happen at dances, but on any occasion where young men and women gathered, even at work. They also found imaginative ways to see each other; for example, when some girls gathered in a house to spend their night cleaning several kilos of corn, the boys who wanted to see them would sneak into the yard where they were sitting, because this work was done in spring or summer, hide in the pile of cleaned corn leaves and talk to each other safely there.

So, somehow, “love begins.” Then, the boy consulted with his parents and, if they agreed, they sent the matchmakers. So, they, not the groom’s parents, nor the groom himself, went to the bride’s house with gifts and asked her parents for her, saying:

“We didn’t come here to eat and drink.

We only came to love you and to see you.

“Give us your girl to marry.”

or “We loved your daughter, we came to take her.”

If they didn’t agree right away, they tried a second and third time. Sometimes two matchmakers would go for two different grooms and the best one would win. When they finally shook hands, they would fire rifles so that everyone would know. On the night of the engagement, the dowry that the bride’s father would give to the groom was also arranged (a field, an ox, 20 sheep, etc.). When leaving, the matchmakers would leave as tokens of the engagement, a gold doubla (large coin) or a fluri (small gold coin) or a medjit (half a lira) that was sewn into the bride’s turban.

If the matchmakers failed, but the young man really wanted to take the girl, just as if the groom’s parents wanted to marry him to someone, but he loved someone else, he would steal her and take her to his house. So he would steal her and they would go to the priest, who would ask the girl if she was with him of her own free will and if she had slept with him; if so, they were free to marry, if not, she could leave (from the story of grandmother Despina Fylachtaki from Katikioi in Eastern Thrace).

Engagement

Tsolakidis Giorgos with his wife Athena and Fylakhtakis Dimitris with his wife Argiri in 1954.

The engagement took place one or two weeks or more after the wedding, on Monday evening for the Eastern Thracians and on Saturday evening for the Eastern Romylians. It never took place during Great Lent (Christmas and Easter) or in leap years. It took place at the bride’s house, where rings were exchanged in front of the icon of the Virgin Mary, gifts were exchanged and a feast followed. In the old days, in the homeland, a common gift from the groom to the bride was the silver belt, a metal belt, silver for the rich, bronze for the poor (bakirozounaro), which the young wives wore around their waists. The bride kissed the hand of her father-in-law, who gave her money and jewelry. In the Eastern Romulan engagement, the groom prepared a ring, a handkerchief and a doubla into which he threw other things, stragalia, raisins, and candies, and the bridesmaids, his parents, but not he himself, took them to the bride. The bride in turn prepared a ring, a shirt, and handmade socks and distributed them. At the end of the engagement, they fired rifles. Now the couple could move freely holding hands, not hugging, so that the world could see them and admire them. The engagement lasted 1-2 years or even longer, depending on the circumstances. During its duration, the couple exchanged gifts.

Wedding

Wedding preparations began long before; the bride had to weave small, white towels, shirts, aprons, and other woven gifts, to offer as gifts to the relatives and guests.

Bride Sultana Fylahtaki. Her father Yiannis and her brother Dimitris have on their shoulders the characteristic woven towels that she had prepared.

A week before the wedding, the girls would go to the bride’s house and prepare the dowries, so that people could see them and admire her skill. After all, she had woven and embroidered them with great care and passion as a little girl for this very moment.

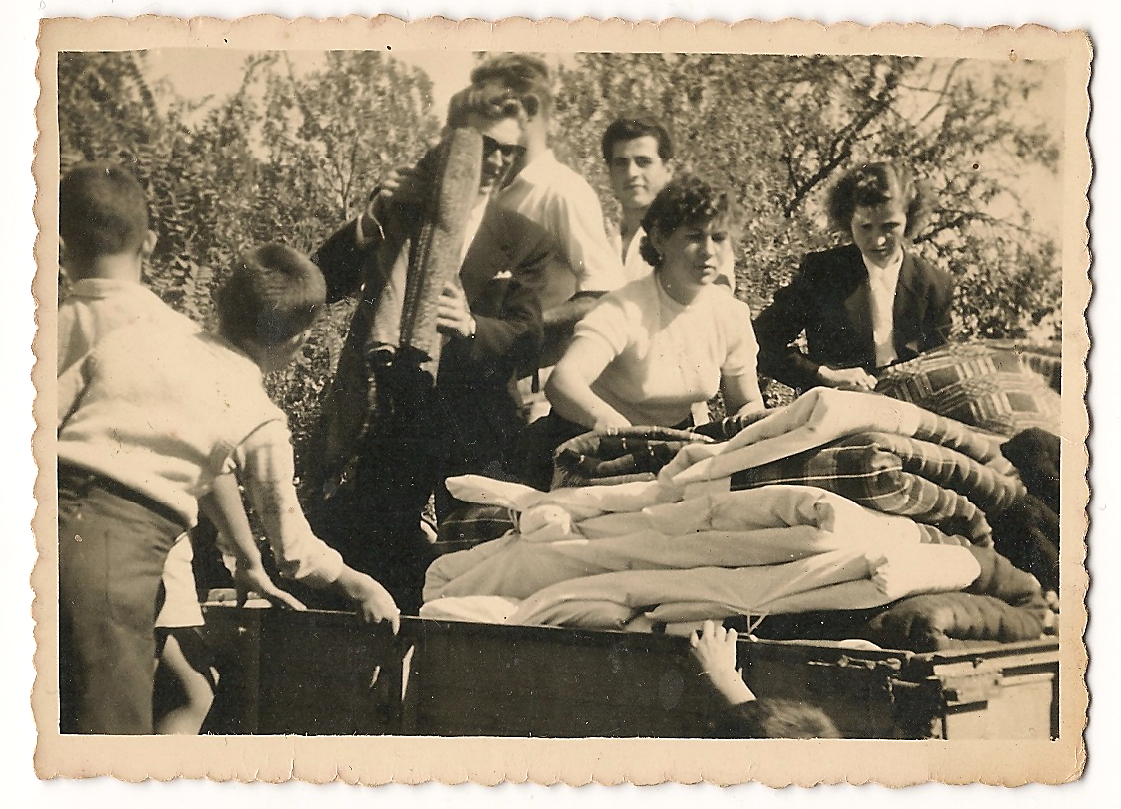

From the wedding of Karamousalidis Christodoulos and Stavrakara Giannoula. Friends of the bride lay the dowries on the cart for the world to see.

On Wednesday they baked a “bougatsa”, that is, a bun like a tsoureki that was broken over the bride’s head on the wedding day, before they left for church. On Saturday they brought the wedding dress and in the evening everyone feasted with their own family in their own homes. On Saturday, they also invited the villagers. Some relatives of the couple would go out with a wooden jug in their hand, the “tsotra”, they would pass by all the houses and invite the villagers, while the Eastern Thracians would treat them to ouzo/tsipouro, and the Eastern Romylians to wine. An embroidered handkerchief was tied to the handle of the tsotra. They were accompanied by the bagpipes, which gave an atmosphere of revelry.

The tsotra

In the past, weddings only took place on Sundays. On Saturday night, the groom’s father would slaughter the animals that would be cooked for the wedding feast, and the women of the neighborhood would come to prepare them. On Sunday, the barber would officially go, accompanied by musical instruments, to shave the groom, while his friends would sing to him. The bride would be adorned by her friends and the maid of honor, and they would also sing to her. She would wear a lot of jewelry, mainly strings of coins, while her house would be filled with youth, people, happy voices, and songs. Then they would break the bun over the bride’s head and distribute the pieces to the people present. In fact, single girls kept their piece and put it under their pillow that night, to dream of the man they were going to marry (this is more or less still done today).

The most official person of the day was the best man, who seemed to move all day long accompanied by his instruments and friends. The procession started from the groom’s house. The young man, his relatives and friends would go to the best man’s house dancing and singing, to pick him up and from there go to the bride’s house to pick her up. The groom would not enter the house, some of his relatives would go and they would have to haggle over how much money they would give the bride’s friends to give her her hidden shoe and let her out. Finally, her father or brother would wash her off. Until she came out of the yard, the bride would cry, either truly or falsely, and they would sing to her:

“Today is a black sky, today is a black day,

Today, mother and daughter are separated.

Give me a mother with my dowry, give me your wish too

“I will pass into another house, I will dwell elsewhere.”

And the mother replies:

“My daughter, wherever you go, don’t look back.”

“Because many have suffered from it, you are not alone.”

So the procession began. The groom was in front with the groomsman (kardasis) and the bride behind with the best man and relatives and the instruments behind, dancing. The groom was forbidden to turn around and look at the bride, but neither was anyone allowed to come between them. The dowry was taken in a cart to the groom’s house. They arrived at the church and the priest took them with him and took them to the middle of the church, where they had previously placed a large white (but not too full) pillow. After the ceremony, the groom’s parents passed first, then the bride’s and then all the relatives and guests, to greet and wish the couple. As they passed, they pinned money and pounds to the wedding dress and the groom’s suit, while the parents wore gold jewelry.

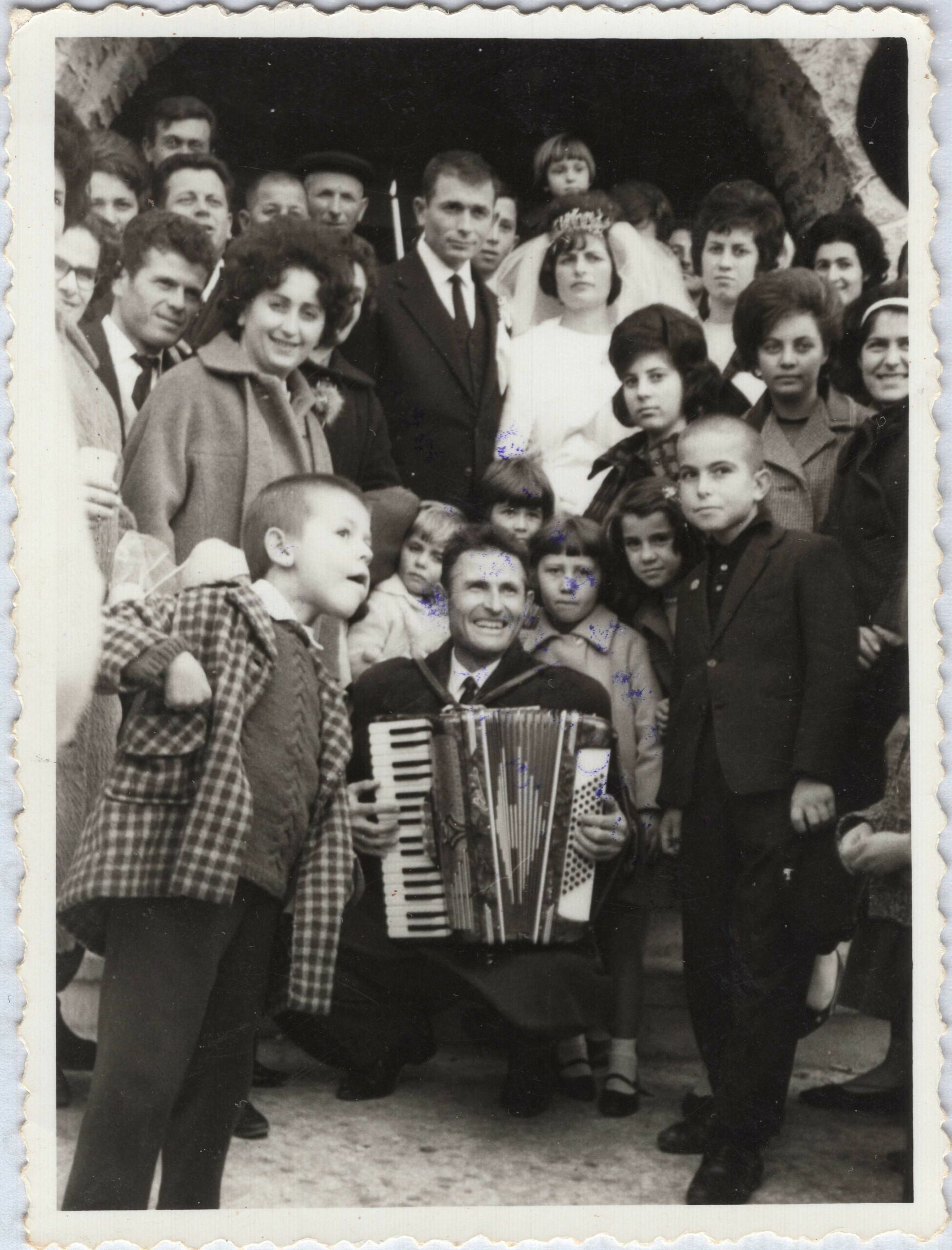

From the wedding of Xanthopoulos Charalambos and Bougioukas Fotoula.

At the wedding of George and Vasiliki Topaki. Next to the bride is Eleonora Stavrakara.

Immediately afterwards, the procession with the instruments would begin for the groom’s house where the feast would take place. Before the bride entered the house, her mother-in-law would wait for her at the threshold to treat her with a spoonful of sweetmeats or honey, so that their relations would be good and sweet (as much as this is possible, of course). Then the couple would step on an iron, a “gyni” covered with a pillow, and they would enter the house. The bride had with her two beautiful bridesmaids, whom she would veil when they arrived at the house. She would also give an embroidered shirt to the groom-to-be, who in the procession would hold a tall stick with a handkerchief tied to its top and walk behind the couple. Upon arrival, the bride’s relatives would take her to dance and continue to pin money on her, as she “draped” them with the fabrics she had prepared long before. The feast was a three-way affair, dancing, food, wishes, revelry, drinking, everything was given in excessive doses.

A nice, big group of people are going to a wedding party. Dimitros Kartalis is the tractor driver and his wife, Fotoula (Stavrakara), is next to him.

From the wedding of Gaitanis Eleftherios and Areti Detaki in 1954.

On Monday, the dowry was hung on ropes in the bridal chamber for people to admire. Another thing that the mother-in-law and then the rest of the relatives had to see first was the bloody sheet from the couple’s first night, to prove that the bride was “good”, that is, a virgin. In fact, they carried it around in a basket and then had another feast with halva, pies, and grilled meats to celebrate (even if the bride was slightly pregnant, the sheet would come out bloody).

As for the other great joy, the birth of healthy children, they had their own way of predicting the sex of the first child. When the bride came home from church, she would throw a tray of candy or rice onto the tiles or over her shoulder to be thrown to the newlyweds. If it landed on its back, it would be a girl; if it landed on its stomach, the first child would be a boy. Another way was to bring two pillows. Without the bride seeing, they would hide a knife under one and scissors under the other and have the bride step on one of the two. If she stepped on the one with the knife, their first child would be a boy.

The traditional East Thracian wedding has some differences, which are as follows: On Monday, the groom would send a bougatsa (roll) to the bride’s house with a young man to request that the wedding take place the following Sunday. If the father accepted, he would cut off a small piece and keep the large one, sending the small one to the groom. Otherwise, he would send the bougatsa back and the wedding would take place the following Sunday. On Thursday, 3 first-born women would gather at the groom’s house and sift flour with the sita (a small sieve for flour) and say:

“Wishes, wishes, my child, on your first roll with daddy’s in the wish”

In fact, as they were sifting and then kneading, they would suddenly throw some flour on the groom. After baking the dough, they would put it in a basket, which was held by three children, who were not orphans, and the three first-born girls would dance around it. The children wore a red fez on their heads. On Friday, the women at the groom’s house would make a kna and “karambogia” to dye their eyebrows. On Saturday, three free girls would take the kna to the bride’s house and dye her hair, fingers, fists and forehead and dance. They would keep this kna and everyone who danced with the bride at the wedding feast would dip their finger in it. Also, on Saturday, they would take the dowry to the groom’s house. After the coronation, the parents passed by, to greet the couple and the crowns, they would put rings, a cross, a watch, a chain, etc. on the newlyweds and sing.

“Enjoy your yoga.”

that brings you partridge

partridge

and holds it in his hands

and kisses her on the lips

or

“Come out, come out, mother-in-law.”

to see your yoga

that brings you a partridge…”

“Come, bride, and kiss your mother-in-law’s hand.”

who planted basil to give you a mate”

“An only son meets in the middle”

in the middle of the sea where a bazaar is held

They were turning the only children with the pearl

and there’s one that’s two or three with an old scooter”

“An only son is known by his walk”

“They stink of his clothes and squeak of his shoes.”

As relatives and friends passed by, they clapped their hands and shouted how many children they wished they could have.

Arriving at the house, the bride, before entering for the first time, in addition to the sweet that her mother-in-law treated her to on the threshold, bowed and entered. The bride had a bridesmaid with her. After the coronation, the groom would take two young men and treat the guests with a bagpipe to accompany them, tsipouro or wine, bowing to them, while the bride would give, as we said, handmade handkerchiefs, woven towels, shirts, etc. to the relatives. After the feast, when they went out to dance, the bride would bow 3 times and throw a handful of coins and an apple for the children to collect. On Monday, a second feast was held with the bride’s relatives. The dowry stayed in the groom’s house for eight days and people would go to see it.

The couple was now bound by the unwritten moral rules of the Greek patriarchal family. One honored the other with a shared dedication to caring for the family, with clear roles and obligations that had to be adequately respected. The man had the final say in everything and imposed his authority even with physical violence, which was legitimate for previous generations. Divorces were then rare to non-existent. However, premature death was common and widowers remarried because they would not be able to make ends meet on their own, whether they were men or women, especially if there were children. The children of the two widows who now became half-siblings were called half-siblings and were equal.

Fylakhtakis Dimitris with his stepmother, Despina, and his little half-brother Alexis.

Birth

The couple Giannakos and Niki Kartali (who is pregnant with their third child, Gianna), on the left Niki’s cousin, Angeliki Dangou, and on the right (Niki’s brother) Thanasis Papantoniou with his son, Evlampios. In front are the children: Dangou Petroula, Kostas and Christos (Takis Tallos) Kartali and Dangou Dimitrios.

After a couple got married, they would wait a few months to announce the good news that the bride was pregnant. If 1-2 years passed and they remained childless, they would start to worry and this would become a topic of conversation among the villagers, whether with good or bad intentions, which is still the case today. Women who could not have children would pray to the Virgin Mary and to Saint Stylianos, the protector of infants, to grant them the most precious gift. When the icon of Saint Paraskevi was found and Grandpa-Goat set up a makeshift iconostasis to guard it, the women who could not have children would go, take a handful of soil from there and see if there was a worm in it, something alive, so it was a good sign, they had hope that they would have a child. In fact, if they found a dead bug, it meant that they would give birth to a dead child. The ideal was of course for a couple to have many children, to be blessed. However, adoption was not excluded, which they did not consider shameful, as in other places, but on the contrary they believed that they were doing a good thing to take in an orphan and give him a home and love. As for the first child, they preferred it to be a boy, but they never went to the extremes of the islanders, who desperately wanted boys. A girl was also a blessing, as long as she was healthy. A humorous quatrain is the following:

“I have a son, I have joy.”

when will I become a mother-in-law?

I have a daughter, I have bitterness.

“I will work day and night”

Papantoniou family in 1940: parents Evlampios Papantoniou and Anna (née Bourazani), Fotoula (the eldest daughter), Niki (the youngest), Froso (the baby) and Thanasis.

We have already said how they predicted the sex of the child when they returned from the coronation. They also believed that a woman would have a boy if her belly was pointed during pregnancy, while if it was round she would have a girl. Also, when they slaughtered a rooster, they took the round bone from its throat and threw it on the tiles of the acheron. If it stayed on top, a girl would be born, if it rolled down, a boy.

Pregnant women had to be very careful, not only about their diet and movements, but also not to provoke their fate by ignoring some unwritten laws. Because it was forbidden to do any work during the three days of the feast of Saint Tryphon, the Assumption of Jesus and Saint Simeon, the first three days of February, as well as to cut anything. They made sure to have the foods they would use on those days ready cut, because otherwise they risked giving birth to scarred or deformed children. Those three days were sacred for pregnant women, they were their feast and an opportunity to rest. They also took care of themselves and were happy, so that their children would be beautiful and happy.

Pregnant women did not work on the feast of Saint Eleftherios and Saint Stylianos either, on the first one in order to be freed easily, that is, to have a good childbirth, on the second because Stylianos was the patron saint of infants. Furthermore, when they encountered an animal on the road, they would lift the rope and pass under it, not stepping on it because the child would be born with the umbilical cord tied around its neck. Finally, a pregnant woman was not supposed to attend a funeral.

There was no doctor in the village. Sometimes someone from the city would come to examine the sick. So the women were delivered by the midwife, the “babo” in their homes. Of course, childbirth is not an easy thing and any complications could not be treated without the resources of a hospital, so unfortunately some women died during childbirth. That is why they said “The woman in labor has one foot in the grave”. So the babo would anoint her hands with oil and “liberate” the woman. Two midwives that our village once had were Stergiani Gaitani and Zacharoula Barbara. As soon as the birth was over, she would wash and swaddle the mother and lay her on the mattress; then she would wash and swaddle the baby in the tub. They would pour hot water and sugar on it to make it “lovely” or salt to make it “tight”, wrap it in its blanket and give it to its mother. The mother would begin to visit her after the third day, while it was forbidden to visit her after sunset. On the three days that the child was born, they believed that the Fates would divide it, so they would decorate the baby and place coins and diamonds on its pillow and gold-embroidered towels and handkerchiefs around the cradle. They would even say to her:

“It has the meaning of a foot in

Don’t cry at all.

“Why did Fate decide to write it tonight?”

Theodoros and Xanthi Tsolakidou with their children, Dimitris, Giorgos and Giannoula in a 1930 photograph.

No warm bread was placed in the chamber of the woman in labor for forty days, and when the sun was shining, nothing was taken out of the house, so that a demon would not suddenly enter and trample the woman in labor and the “salo”, the baby. After sunset, no one visited the woman in labor. Even her husband had to return home before nightfall; if he was late, the grandmother had to light coals in the censer and take it out the door, or at least the man had to take off and leave one of his clothes outside and not go immediately to the woman in labor, but spend some time in another room. Not even baby clothes were left hanging outside at night. Furthermore, the midwife would take a bottle of water to the priest, read it, and with this holy water they would sprinkle the forehead of the woman in labor and the baby every morning for forty days for health. The woman in labor stayed at home for forty days, did not visit any house and did not go out on the street, mainly so that she would not meet another woman in labor or a new bride and be “stepped on” (suffered harm) and her milk would be cut off, or so that she would not be cursed. After all, they believed and we believe a lot in the evil eye. Thus, so that the baby would not be cursed, they would put a coin, a blue bead or a cross in his cap, and in his cradle they would hang an amulet in a small triangular bundle, in which they would put holy wax, a wick from a candle of the Virgin Mary or Christ, three peppercorns or cloves or frankincense if they could find it, while at its two ends they would sew a blue bead. Furthermore, when someone went to the birthing place, she would leave a few threads from her dress for the baby and if they happened to peek, they would smoke them with these threads. Finally, they avoided looking intently at the child so as not to embarrass it, and when they were happy, they would say “ftu skorda”. At forty days, the mother would take the baby and go to church to receive the forty-day blessing, which is a short ceremony of welcoming the new person into the church. As she went, her mother would sprinkle the road she passed with the holy water (which we mentioned before) until the bottle was empty and then she would enter the church. If the woman in labor left the house before forty-day blessing, it was said that wherever she stepped, no grass would grow. After forty-day blessing, the mother would visit three relative’s houses.

If a baby was grumpy, crying and not feeding, a friend would take a swaddle and when the herd was returning from a crossroads at night, she would throw it on the ground and when three cows passed by, she would grab it and, without speaking to anyone, she would go and swaddle the baby. This would happen for three nights and the baby would finally calm down. The babies were swaddled tightly, tightly so that their little bodies would develop properly and so that they would have straight legs. Of course, the infants did not like this at all, who would be sad in their narrow woolen prison and cry. In the first year after the child was born, the grandmother would receive her last gift, a rooster if it was a boy or a hen if it was a girl. Relatives and friends would constantly come to see the newborn and, along with their gifts, mainly clothes, they would shower him with gifts, just like today.

When the child grew a little and crawled, they would hide three objects that symbolized three professions, the scissors of the tailor’s profession, the knife of the rancher or butcher, and some agricultural tool of the farmer, and they would watch to see which one the baby would find, so they would say that this profession would follow when he grew up.

Lullabies:

“Sleep, my little bird.”

and your luck is working

and your good radical

“He carries you, he brings you”

“Sleep nourishes children”

and hello makes them bigger

and the wax Virgin Mary

“Good night to them”

(from left) Bourlouka Machi with her child Vangelis, Christoforos Georgia, Eleftheriou Maria, Tsolakidou Margarita, Lampaki Evangelia, Fylachtaki Argyri, Tsamourtzi Paschalio with her son Dimitris, Balambanis Katina, Karamousalidou Giannoula and Irini, Tsolakidou Athena, Tsatrali Vasiliki, Christoforos Giannoula, Mitreli Soultana, Tsolakidou Xanthi, Eleftheriou Afentia and her mother Areti, Tsolakidou Kortesa, Stavrakara Loulouda, Eleftheriou Efthymia.

(from left) Bourlouka Machi with her child Vangelis, Christoforos Georgia, Eleftheriou Maria, Tsolakidou Margarita, Lampaki Evangelia, Fylachtaki Argyri, Tsamourtzi Paschalio with her son Dimitris, Balambanis Katina, Karamousalidou Giannoula and Irini, Tsolakidou Athena, Tsatrali Vasiliki, Christoforos Giannoula, Mitreli Soultana, Tsolakidou Xanthi, Eleftheriou Afentia and her mother Areti, Tsolakidou Kortesa, Stavrakara Loulouda, Eleftheriou Efthymia.

BAPTISM

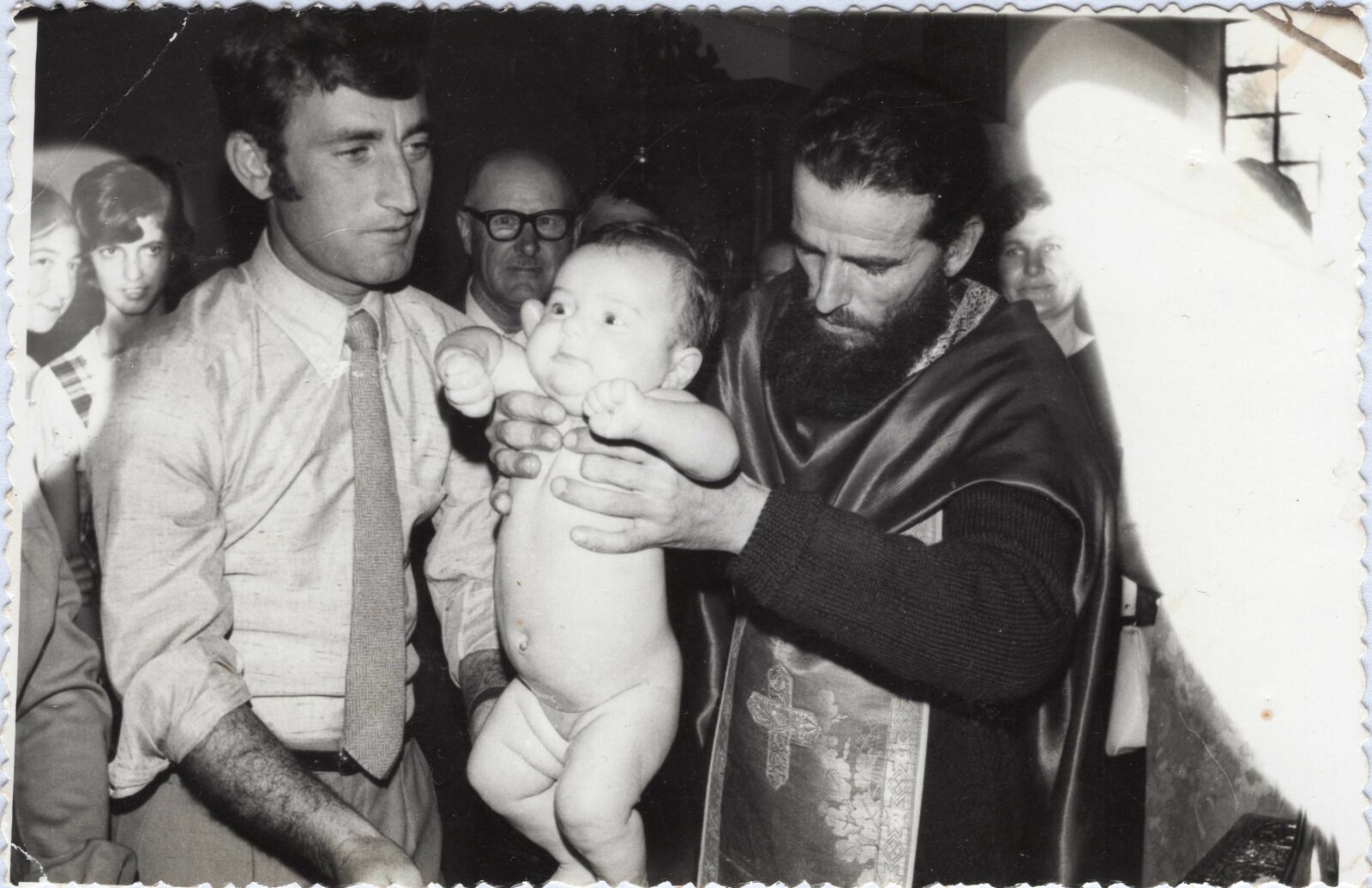

From the baptism of little Kostas Akhtaris

In the past, the people of Eastern Thrace baptized their children before they were forty, it was a sin to baptize them afterwards. The people of Eastern Romulus always did so after forty. On Sunday morning, they prepared the food. The midwife would take the baby to church, after she had dressed him herself at home, together with the godmother. Today, the parents take him with the godmother. As soon as the baptism was over, the godmother would dress the child, take him and take him home. The mother would go out to the door and after making three penances and kissing the godmother’s hand, she would take the child into her arms. She would also give the godmother a present.

For three days, they did not wash the baby and his clothes from the holy baptismal oil and they wore his cross for these three days, which they removed later if they wanted. On the third day, the washing of the oil took place, that is, the godfather or godmother washed the baby and his baptismal clothes from the baptismal oil and threw the water in a place that was not stepped on. This is exactly what is done today. The parents and the godfather did not say the child’s name until the baptism, not even at night, so that it would not come to harm. However, mortality was once high and infants were in danger of getting sick and dying before they even reached forty. So if he did not have time to be baptized, the midwife would take the baby in front of the iconostasis, say “I believe” and “Apotheosis Satan” three times, cut a few hairs from his head, sprinkle it with oil from the lamp and give him his name, this process is called lamp baptism. There is also air baptism, which is done without oil only in front of the iconostasis, again raising the child up and down three times as if baptizing him in the swimming pool. The oil and the baby’s hair from the lamp baptism were thrown into the church’s crucible. If he eventually lived, they would rebaptize him normally with the same name.

Kostas Stavrakaras is the godfather at the baptism of Fotis Koutaliou. The priest is the long-time vicar of our village church, Father Fanis Bouboukis.

Children’s toys

“To dance and be happy”

now that he is a young child

and tomorrow as if he’s getting married

“He will enter into suffering”

The children helped their parents as much as they could with housework and fieldwork, while also taking care of their younger siblings, but when the chores were finished, they made sure to have fun and play, as no child plays today, in the age of screens .

dolls

The little girls had their dolls. Because buying dolls was expensive and in the past there were no ready-made dolls, they would make them at home with simple materials. They would take two sticks, one longer and one shorter, and tie them crosswise. The small stick represented the hands. The head was usually made of plain cloth, preferably white, and a little cotton. They would paint the eyes, nose, and mouth. They would make the dress from another piece of cloth and the doll would be ready. They also loved to play with the baby animals in the house, which they would take care of like mothers.

Bones or small bones

Guts were played in various ways. It was usually played with two children sitting on the floor facing each other and with five or more guts. They would throw four guts on the floor and with the right hand they would throw the fifth one up and until it came down and they could catch it again with the right hand, they would pick up the guts from the floor first one by one, then two by two then three and one and finally all together, always using only the right hand. They would often paint the guts to make them more beautiful. In another version, they would throw a volley and have to set up six bones.

It flies – it flies

All the children sat on the floor or on the ground and put their little finger (index finger) all on one spot. Then the mother would say “the bird is flying” and raise her hand up. The others did the same. She continued saying “the butterfly is flying, the eagle is flying, the donkey is flying”. Some of them, in their haste, would raise their hand to the donkey and lose. But they would burst out laughing and the game would continue.

The long-ass

The children would bend over one behind the other in such a way that the head of one would touch the bottom of the other. After 5-6 children in a row had bent over, then one child would run at full speed and try to jump over the first one and sit on his back. Then he would go to the end of the row, bend over in the same way, and the game would continue.

Chillik’

For this game, two sticks were needed, a small one about fifteen points long with pointed ends and a large one about half a meter long and this was the tsilikomana or tsilikoverga. The child who played first would put down the small stick and hit its end. The stick would jump into the air and then he had to hit it again with the tsilikoverga so that it would go far. Other times they would touch the mixed stick to a stone in such a way that one end of it touched the stone and the other on the ground. They would pass the tsilikoverga into the gap that was created, raise the tsilikoverga up and hit it again to go far. Another way was to dig a small hole and put the tsilikoverga so that half of it was in the air and they could hit it.

The other child, who was far away, would try to catch the tsiliki and if he succeeded, he would send it back to the one who hit it, who would hit it again with the tsiliko rod. In this game, they set various rules. One was that any child who caught the tsiliki would switch places with the one holding the tsiliko rod or tsilikomana. Another rule was that if the player failed to hit the tsiliki three times, he lost. Also, to count who hit the farthest, they would count with the tsiliko rod, saying tsiliko chomak, tsiliko chomak.

Saita/Chatal’ (slingshot)

They took a strong, forked stick, the chatal, about 15 points long. At the two ends of the fork they tied a rubber band as thick as a finger, and about 30 points long. In the middle of the band they placed a small stone. With their left hand they held the chatal and with their right they squeezed the small stone that was in the center of the rubber band. They stretched the rubber band and let go of the small stone. It would fly away. They placed many bets on whether they would hit a target with the small stone.

The Biz

This game was played mainly by boys. The child who was guarding had his back turned to the other children. With his left hand he hid his face (his eyes) and with his right he passed it under the armpit of his left hand behind him, with the palm turned outward. One of the children playing would clap his palm and shout “biz”. The child who was guarding would try to find who hit him. If he found him, they would change places. Otherwise, he would continue this until the child who would hit him was found.

The Mosque

The children in this game were divided into two teams. One guarded the mosque which consisted of pieces of tile stacked one on top of the other. The other team was about five meters away. where a line had been drawn and held a ball (topi). A person from the second team from the distance of the line would mark the mosque with the ball and try to throw it. If he threw it, the ball would go to the team guarding the mosque. The team that threw the mosque would try to rebuild it and the team that had the ball would throw it from one child to the other until they found the right moment when someone from the other team would try to place a tile on the mosque and hit it with the ball. If he hit a child, that child would burn and leave the game. When the team had placed all the tiles and erected the mosque, they all happily shouted the word “mosque” and the teams changed positions.

Little goats

That’s what they called hide-and-seek and they only played it at night, apparently to make it more difficult.

Slave girls: in a corner of a building there were some slaves. The liberator would touch the slaves one by one and free them. They had to run to avoid being caught.

Three, it was the triplet.

In the winter when they couldn’t go out, young and old would play, saying “in the village in such and such a neighborhood there is a man, a woman, two children, a grandfather… who are they?” and the other person had to find it. Another great pleasure was swimming in the lake, which their parents often argued about. Today, this image comes to life again, when in the summer the children gather in the village for the holidays and, like back then, girls and boys gather in the square and play their own games, in addition to the old ones, apples, archery, rubber bands, marbles, basketball, bicycle races, lice, etc.

The boys, being the most lively, formed a large group and played soccer with a cloth ball, chase, again divided into two teams, trying to free their own from the prison where the other team had thrown them, etc., making the village echo with their voices.

When they wanted to divide into groups or choose between two things, they would say the following verses, which were a series of improvised, incomprehensible words, “unsuitable” for adults:

“One mani doo doo mani”

three rom caza com

com com pitsi keli mantra keli vam

chi-chi rak michi rak

“pliam plik” (its place has now been taken by Abe ba blom

Death

Every person is born with their destiny predetermined, their little lamp is lit when they come into the world, which they leave only when their little oil is saved. No matter what they do, they cannot escape their destiny, which is why we often say “If it is written to find you, no matter what you do, wherever you go, it will find you”. Death was, after all, something very familiar to the generation of the first inhabitants of the village, since they had known wars, diseases, hunger, refugees and mortality was high. But the pain and fear of death, no matter how inevitable it is considered, is great.

“Why are the mountains black, why are they withered?

Let no wind fight them, let no rain beat them

Only Death passes with the departed.

drags the young in front, the old behind

He drags even the little children in the saddle, scattered about.

The elders beg and the young kneel

and the little children with their arms crossed

You were passing through Haro from a village and sat in a cold fountain

Let the old people drink water and the young people turn to stone

and the little children will pick flowers.

If I pass through a village down to a cold fountain

Mothers come for water, they know their children

“They know the husband and wife and they have no separation.”

The perceptions of death and the afterlife of the Thracians in general, and of the Plastirians in particular, are distinguished by their deep religious feeling, but also by a significant dose of pre-Christian spirit. They therefore believe that the soul of a person does not come out and torment him, if at the moment of the death throes someone is in the room and scares him with a word or a sob, then they say that he is “angel-beaten” and is very tyrannized until he is finally freed. This is perhaps why they do not let children stay in the room. It is necessary for the sick person to take communion first, so that he is ready to be judged by God and go to Heaven. The last moments are the most important for a person and in them he seeks to do something to save his soul.

However, the soul does not go to its final destination, Hell or Heaven, until after 40 days (another concept with a purely pagan basis). Until then, it circulates in the house among its household members and especially at night it stays in the room, where it was completely separated from the body. Thus, during these 40 days the room remains empty with only a candle burning in the middle, while depending on the behavior of the household members it turns into a good or bad spirit, it becomes a vampire. To prevent it from becoming a vampire, they are also careful not to let a cat pass over it, and when it dies they turn the mirror upside down. Someone from its family closes its eyes.

Then the shrouder takes him and dresses him in his best clothes, combs his hair and prepares him to be placed in the coffin. The coffin is placed high (not on the floor), with the head of the deceased facing west, his arms crossed and among the flowers. The coffin has a white cloth. The young men are dressed as grooms and the young women as brides. Behind his head they place a large candle, with a black or white ribbon, depending on age, and an image of the Virgin Mary or Christ on his chest. The window of the deceased’s room and the doors of his house are wide open, so that Death can easily enter and take the soul. The deceased remains in his house for 24 hours so that relatives can mourn him and friends can visit him. His own people arrive throughout the day, offering a candle and flowers. They buy the candle from the church and do not put it inside, but place it outside the door. If they cut the flowers from the garden, they cut them with scissors and pay the house that gave them to them, they water them outside the house of the deceased and leave them outside too. When entering, they do not greet anyone, they only say “Life to you according to your word”, “Live, remember him”, “Good patience, may you not see any more evil”, “God have mercy on him” or “God rest him”, they light the candle in the box with the wheat or flour (if the deceased died young or old respectively), which they have placed next to it, they incense the relic, sprinkle it with the flowers, do three penances and cross themselves three times, they bow to the icon and kiss the deceased on the forehead. They were careful not to let a tear fall on his clothes because they would see him in their sleep. They did not leave the deceased alone at all, so that he would not become a vampire, nor did they sweep while he was in the house. They did not have fortune tellers, nor did they mourn themselves, sometimes someone from the house would sing or not, the merits of the deceased. At the same time, they read in turn (perhaps to pass the time at night) the so-called psalter (Gospel).

The next day, they lift the relic before sunset of course. They collect the flowers that are on the deceased and put them on the pillow made of linen cloth in the house, which is sewn by all the women there, not just one. This is placed at his feet in the coffin. Once upon a time, they would put a coin in the mouth of the deceased, so that he could give it to the angel and cross the bridge (or the river), a custom that is purely ancient Greek, which is why it was forbidden by the Church. In Eastern Rumelia, they did not take the deceased out of the door, but they would tear down a part of the wall and carry him through there, if he had died in the three days after Carnival Sunday. First in the procession is the priest and the children with the cross and the six-winged wings, the coffin, and then first the women and then the men, who are always the bravest. As the funeral procession passed through the village houses, no one remained lying down, it was bad.

Close relatives and friends follow to the cemetery. The priest reads a prayer, the relatives, after giving their last kiss to their deceased, lower him into the pit. Then the shroud descends, unties the arms, legs, and jaw, covers his face, takes the pillow with the hair (because if the pillow is made of wool, the bones of the deceased turn black) and puts the one with the flowers on it. The priest pours water over the deceased, making three crosses, and everyone throws a little soil on the grave three times, saying: “You are soil and to soil you shall be.” If someone sneezed during the funeral, in the past they would tear a piece of their clothing. After burying the deceased, everyone washes in the stream or fountain, and whoever cries a lot wets her handkerchief and they head home, after distributing boiled wheat and cookies.

There the Trisagion and the blessing take place. In the room where the deceased rested, they have a small table and on it a glass of wine, an offering, a censer and his candle. The priest incenses everyone, reads the Trisagion and gives the consolation, cuts a mound from the offering, rubs it in the wine and gives it to the relatives with a small spoon. Then they have everyone who has returned from the grave eat and mourn the deceased. In the past, they would spread a tablecloth on the ground and lay out fasting food, beans, olives, lathiri, pilaf, cheese and steamed bread, which they cut by hand.

Women now wear black and mourning used to last forever for the widow (unless they remarried) and from one to three years for the other family members. Men remain unshaven and wear a black shirt until the forty-day memorial service. Furthermore, in the past, on major holidays (Christmas, New Year’s Day, Easter) they went to Church, but they did not take communion, they did not clean the deceased’s room, they kept the window open so that his soul could easily come and go, they did not cook, but neighbors and relatives sent them food. Until the deceased became chronic, they did not treat them to sweets at home, but coffee and raki. For two more years, they did not wash or bathe on Saturday, and on Easter they did not dye eggs, or they dyed them black. The neighborhood supported the relatives in their mourning, they did not leave them alone, nor did they party for a long time.

Memorial services are considered the most important thing for the soul and its peace in the other world, and when they are not held, the deceased does not rest, appears in the dreams of relatives, disturbs them and it is not excluded that something bad will happen to them, as punishment for their indifference. The memorial services established by the Church are the following: the three-day, the nine-day, the twenty-day, the forty-day, the three-month, six-month, nine-month, the year, the two-year, the three-year and when they are buried at seven years. During the memorial services, they prepare the boiled wheat, the kolliva, that is, they take it to the church to be read, they make a trisagio at the grave and distribute the kolliva. During the three-day and nine-day services, they do not add flour or sugar to the wheat, only spices, cumin, cinnamon and form a cross on top with a walnut. Forty is always a Sunday and always a few days earlier than the regular date. They make a lot of kollyva and it is done with a collective service, all the church candles are lit and candles are distributed, when they boil the wheat, they leave it uncovered so that the steam goes to the soul, after the memorial service they set a table for the “schorio”. The people of Eastern Romulus would make a small plate of “kassia” for the dead, that is, a cream batter with milk and flour, a hot bun and distribute it. They would put an incense burner, the kassia, a bottle of water and a bun if the deceased was a man or a liturgy if it was a woman in a pan and they would distribute them in the neighborhood every day for 40 days, they never distributed eggs, because as they said “in another world there were kouts’lies”, nor meat.

Every seven years, the exhumation takes place; on Saturday after noon, they take the priest and go to the cemetery, perform a trisagion and exhume the deceased, wash the bones with wine and put them all in a bag, relatives and neighbors bring candles, flowers, incense and after lighting the candles, they incense the bones and share the offerings.

Other days dedicated to the worship of the dead are the Soul Saturdays, there are mainly four a year, of which the one preceding Pentecost and the Holy Spirit is called “Great Soul Saturday”. It is an ancient tradition to worship the dead on certain specific days and throughout Greece these days are Soul Saturdays, precisely when, tradition says, the souls of the dead, like invisible spirits, visit their home and grave and stay outside for twenty-four hours. That is why it is the obligation of relatives to take care of them, especially in the first three years.

Thus, the deceased’s family visits his place bringing flowers, oil, incense, candles, kolliva and wine or water, they clean the grave, decorate it with flowers, light the lamp and candles and perform a trisagio, the priest pours the wine or water on the grave – the libations of the Ancient Greeks – and distributes the kolliva to those present.